Writers: Stop it with the AI images already. You're next.

The time is again ripe for targeting the “machinery hurtful to commonality.”

There are smart people I follow on Substack and other platforms who put AI generated images in every post, because all the blogging guides say “Make sure every post on your site has at least one image to add visual interest." Before DALL-E and AI, bloggers often used stock photos, usually from the free sites where you get what you pay for. When the last owner of Treehugger insisted that I use Getty stock photos for every story, I would look for the tackiest ones I could find, ones that broadcast “STOCK!”, but when they “updated” my older posts with new photos, they often outdid me in tackiness.

I can see the attraction of the AI and avoiding stock photos. But I am not putting an image at the top of this post because I have a question for all of those writers using AI images: what are they thinking?

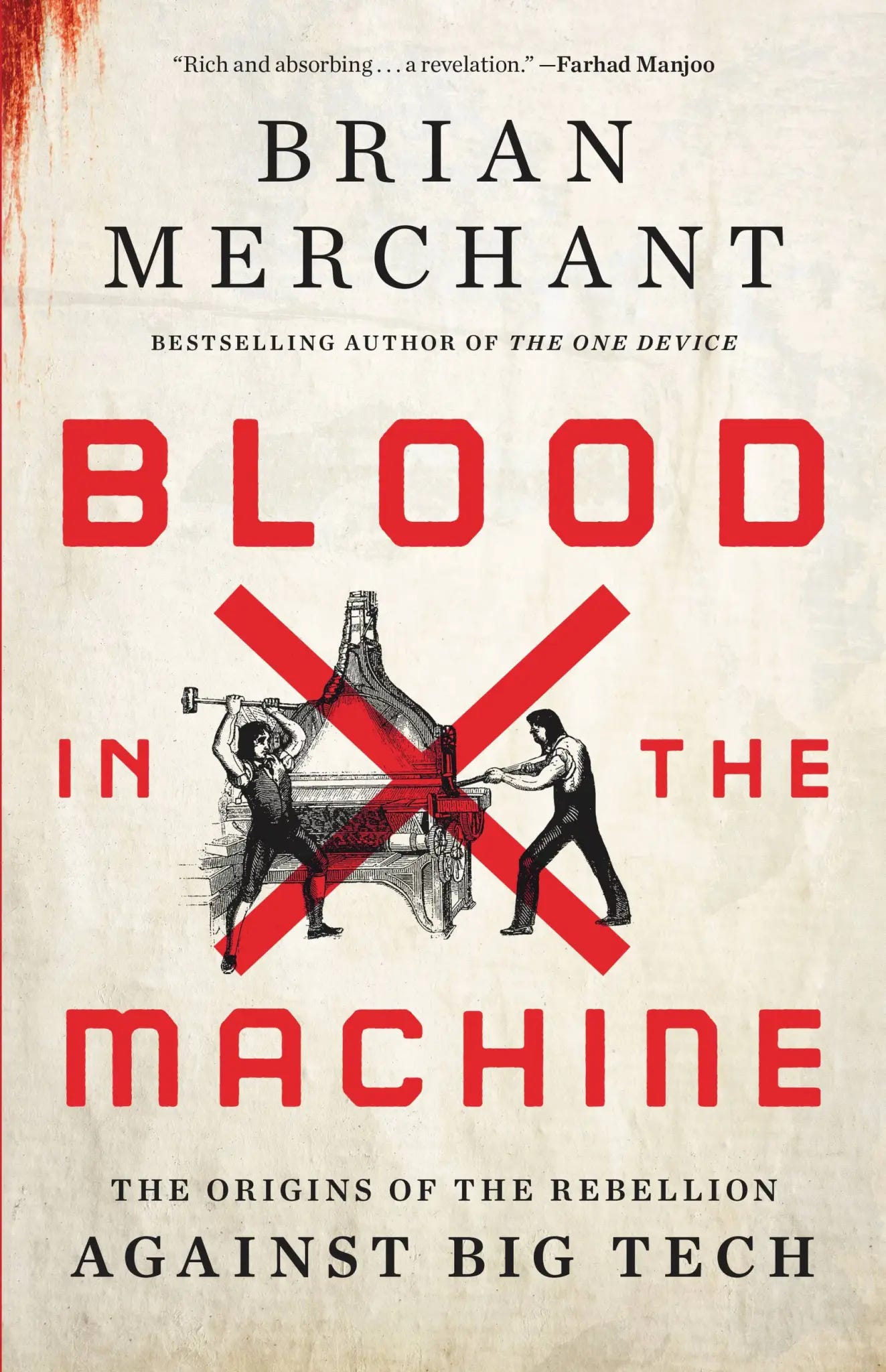

I just finished Brian Merchant’s brilliant book, Blood in the Machine: The Origins of the Rebellion Against Big Tech, where he explains that the Luddites didn’t object to technology; they were often masters of it. They objected to exploitation, to being put out of work by machines that did a crappy job but could be operated by children and could turn out massive quantities of cheap goods fast and make the owners extremely rich.

In the last chapter, Brian compares this to what is happening today, where thousands of journalists, writers and other workers are being laid off, in part because of the promise of AI.

“Robots are not threatening your job. Gig app executives who sense an opportunity to evade regulations and exploit tradition-bound industries are threatening your job. Business-to-business salesmen promising AI content and automation solutions to executives are threatening your job.”

Many suddenly self-employed journalists and writers then set up on Substack or Medium or LinkedIn and what are they doing? They are using AI generated images. Perhaps it is to avoid taking a photo or paying for one, or maybe they think it’s fun and are getting into it; here’s an example from one of the smartest energy guys on the net; I think it demeans his work.

Tech changes have roiled the media business for decades. My father-in-law Bill was a printer, a member of the Toronto Typographical Union that I have previously noted was responsible for the invention of Labour Day. He went on strike against the Toronto Star in 1964; As PrintAction notes, their services were no longer needed. “Harris Intertype and Mergenthaler Linotype along with Fairchild had developed faster tape-based machinery driven by newfangled computers. These devices could spit out miles and miles of perforated paper tape.” John Bassett, publisher of the Toronto Telegram, said, “I think the future of Canadian newspaper publishing is bright, provided publishers assess accurately the changed role of a newspaper and also take advantage of new automated processes… The main problem facing publishers is that of rising costs.”

On the other hand, spouse Kelly reminds me that printers like her dad died young from toxic inks and lead poisoning and getting crushed in giant machines, and the technological changes saved lives. Those newfangled computers got smaller and cheaper and created millions of jobs, including mine. But those new automated processes keep getting slicker, the new media publishers keep wanting to drive down costs, and where does this end?

Scientist and author Gary Marcus doesn’t even think AI should be short for Artificial Intelligence; he says it should stand for Alt Intelligence.

Alt Intelligence isn’t about building machines that solve problems in ways that have to do with human intelligence. It’s about using massive amounts of data – often derived from human behavior – as a substitute for intelligence.

Not just intelligence, but also talent and creativity. It’s a cheap substitute for you and me and tacky stock photo photographers and everyone who ever held a paintbrush, a camera, or a keyboard.

A week ago, I was writing about recycling and was looking for a photo I knew I had somewhere of a Tim Horton’s cup in a ditch. I couldn’t find it, and thought I would try DALL-E to generate one. It was awful, because just as having a word processor doesn’t make you a writer, having DALL-E doesn’t make you an artist.

Frustrated, I went for a run, and happened upon some garbage thrown out of a truck window into the gutter, and used a photo of it instead. And I decided that from now on I would rather take a photo of a pile of garbage than use an AI image.

I am considering unfollowing every writer that uses AI images and letting them know why. It’s like the Martin Niemöller poem, “First they came…” for the photos. And we are next.

Last words to Brian Merchant:

The time is again ripe for targeting the “machinery hurtful to commonality”—the gig app platforms, the fulfillment-center surveillance, the delivery robots, the AI services, the list goes on—duly singled out by those whose livelihoods are being migrated, against their will, by this generation’s tech titans, onto unforgiving technologized platforms, or degraded and whittled away by automated systems.

I'm tired of AI images, their gauziness, which I assume is there to sidestep copyright on the photographs and images they use, just looks like a crapy artist trying to cover up poor technique.

And writers, AI is being used in your jobs. A colleague recently lost a position working in marketing to AI. She's had decades of experience and been part of editorial teams working on bestselling books.

I review books on my Substack, and publishers send me their wares for review. Some of these books are produced, in part, with AI. The first chapter reads just fine, then, starting with the second chapter, I can tell that AI was used for much of the rest of the book. Sure signs are a slight change in tone, the overuse and misuse of the rule of three, and a sameness of paragraph construction. I won't review these books.

I have a client (whom I love!) who uses AI images to illustrate every story I wrote for them. I have wondered if I should say something about it because it made me uncomfortable: Your post galvanizes me to bring it up. Thank you.