We don't just have a disposable cup crisis; it's a symptom of a much bigger problem.

We have to change the culture, not the cup.

I have been overwhelmed by the kindness and the support I have received since my recent 1st-anniversary post, and I want to thank you all. I also want to apologize for a lot of quoting of my past work in this post, but it is a subject I have obsessed about for years.

The Guardian recently titled an article The disposable cup crisis: what’s the environmental impact of a to-go coffee? They note that the cup has a carbon footprint of about 110 grams of CO2. That’s the number How Bad are the Bananas author Mike Berners-Lee and I use in our books, and it’s not on its own a very big number; the latte inside the cup is 550 grams. However, it adds up; 6.5 million trees worth of paper go into 16 billion disposable paper cups every year.

But the real problem is not the cup itself; it’s what the cup and single-use packaging have wrought, which is what I call the Convenience Industrial Complex, a play on President Eisenhower’s killer farewell address where he complained about the Military Industrial Complex. In that same 1961 speech, this Republican President also noted:

As we peer into society's future, we – you and I, and our government – must avoid the impulse to live only for today, plundering for our own ease and convenience the precious resources of tomorrow. We cannot mortgage the material assets of our grandchildren without risking the loss also of their political and spiritual heritage.

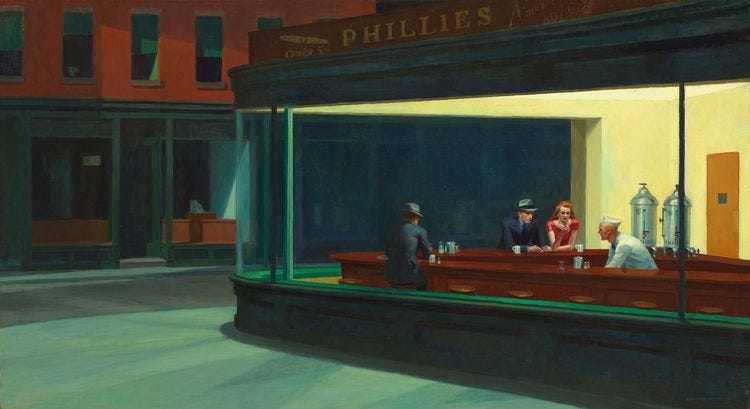

In our grandparents’ era, if you wanted a coffee, you went to a diner, sat down and drank five ounces from a ceramic cup. If you were lucky, they offered free refills, but usually not; real estate is expensive, and they wanted turnover.

As Americans moved to the suburbs in the 1950s, the way we ate and drank began to change. In my upcoming book from New Society Publishers, The Story of Upfront Carbon, I blame the McDonald Brothers. “This was the true start of the extravagantly wasteful linear food system we have today. The McDonalds refused to provide any indoor seating; there might be a few picnic tables, but customers were expected to eat and drink in their cars.” As Emelyn Rude writes in Time: "By the 1960s, private automobiles had taken over American roads and fast-food joints catering almost exclusively in food-to-go became the fastest growing facet of the restaurant industry."

Everything changed because of this. Our cars adapted too, getting bigger to accommodate their transformation into mobile dining rooms. Nancy Nichols wrote in The Atlantic five years ago:

The 2019 Subaru Ascent will have 19 of them. Not airbags, but cupholders. That’s more than any mass-market vehicle ever produced, amounting to almost two-and-a-half cupholders for each passenger. There’s room for a Starbucks skinny latte, an unnaturally colored Big Gulp, a Yeti Rambler, and juice boxes galore. So many cupholders, in fact, that The Wall Street Journal recently declared: “We are approaching peak cupholder.”

Not even close. Cars get wider every year, and so do the centre consoles, which are now the size of TV table trays; you can dine as well as drink on them. One has to ask how much of the car and truck bloat we have is due to their role as dining rooms; Nichols notes that cupholders are “a key feature that shoppers evaluate when purchasing a new car, even for a time supplanting fuel efficiency as a consumer’s most sought-after attribute.”

The cupholders have to adapt to the ever-larger cups; since we weren’t clogging their real estate, vendors could increase revenue by making the drinks bigger and bigger. They made it easy for us to always be sipping something, which is why you now find cupholders in everything from shopping carts to baby strollers.

The entire industry is built on the linear economy. It exists because of the development of single-use packaging, where you buy, take away, and then throw away. It is the raison d'être. They pretend to care about sustainability; Starbucks even built a drive-thru out of shipping containers and covered it with a million R-words, yet doesn’t offer reusable cups there. I complained, “This building is just another cog in sprawl-automobile-energy industrial complex that we have to change if we are going to survive and prosper. We have to stop sprawl, not glorify it; covering it in the R-words is sanctimonious and delusional, and Starbucks knows it.”

The Guardian notes that Starbucks and other companies are offering discounts for people who bring their own refillable cups, but as I wrote in my book (yes, there is a section on coffee cups), it’s not going to work:

Many companies have tried promoting refillable cups, better cups, recyclable cups, and tried to make the linear process circular.

With coffee cups, for example, there have been attempts at putting RFID chips in them where people buy it at one store and drop it off at another, or even just giving people a reduction in price if they bring their own cup, which a very small percentage of the population will bother to do. But it is not enough to change the cup; we have to change the culture, the entire concept of takeaway coffee, soft drinks and bottled water.

The problem is that it is hard to bend a linear economy into a circle. It wants to stay linear. We have been trained through convenience and lack of alternatives to accept that the world is linear. Layla Acaroglu has written that this is all by design, to get us to consume more.

“The systems of disposability permeating our lives are a product of economic incentives and the systems archetype of a race to the bottom, offering the cheapest price tag by the producer and the most convenient solution to the ‘consumer’, at the cost of the society and the planet. But whilst it may seem like cheaper products are better for the consumer, the net gain is always skewed towards the producer.”

Then there is the classic question of boundaries. It’s bigger than the cup and the car. The average customer at the drive-thru window waited 4.4 minutes in 2018; it is probably longer now. According to Natural Resources Canada, 10 minutes of idling burns .25 litres of gasoline; 4.4 minutes burns .11 litres. Burning a litre of gasoline releases 2.3 kg of CO2, so the average idle time waiting for that cup of coffee releases 253 grams of CO2, well over twice what making the cup purportedly releases.

The cup, the cupholder in the SUV that’s big enough to be a mobile dining room, the need to always be sipping something: that’s the system, the culture of convenience. That’s why we have to change the culture, not the cup.

My former Treehugger colleague Katherine Martinko described drinking coffee in Italy:

“While travelling in Sardinia, Italy, my husband and I stopped at a small roadside bar for an early morning coffee. The barista pulled our espressi with a deft hand and pushed two white ceramic cups and spoons across the counter, along with a little sugar dish. We stirred, drank it in a few gulps, and chatted briefly with the other people lining the bar, also enjoying a quick coffee. Then we headed back out to the car and continued on our way.”

We moved out of the diner and into the car, so the cups got huge, and we sip all day as we drive. Yes, disposable coffee cups are a problem, as are disposable straws, but they are just symptoms of the much bigger crisis. I wrote in a Treehugger post:

The problem is that, over the last 60 years, every aspect of our lives has changed because of disposables. We live in a totally linear world where trees and bauxite and petroleum are turned into the paper and aluminum and plastics that are part of everything we touch. It has created this Convenience Industrial Complex. It's structural. It's cultural. Changing it is going to be far more difficult because it permeates every aspect of the economy.

But then I was surprised this year while teaching at Toronto Metropolitan University. To set an example for my students, I bring a refillable cup to class, which I fill in the nearby dining hall. One day, I forgot it and looked for paper cups, and there were none; apparently, the university banned them from their catering operations, and I had to teach decaffeinated. It wasn’t so terrible; we really don’t have to be sipping every moment. I didn’t fall asleep or die of dehydration. Perhaps we can change this perma-sipping culture of convenience after all.

I’m amazed how much young people eat out and their size. Do we still cook? But people eat out in Japan too without a culture of trash or being overweight. The petroleum industry is all about convenience for mobility, the liters/takeout number for supersized food and SUVs-mobile dining rooms- is informative. Also unlike Japan an increasing population live in cars and cities wrestle with safe parking lots to temporarily store them.

Just a quick note to say thanks for this. My work is so focused on other topics recently that I rely on sources like this to keep informed on ee challenges and strategies.