Why we need to re-learn how to sail our buildings

A new study goes medieval on the conventional wisdom about comfort.

When I was young, I sailed my Laser or my father’s Alberg 30. I would read the wind and the weather, constantly adjusting the sheets and trimming the sails to achieve maximum speed.

This is why I was so intrigued when I saw the title of a paper in Buildings and Cities: Learning to sail a building: a people-first approach to retrofit. Because that is what everyone did before they had furnaces and thermostats and cheap fossil fuels; they sailed their buildings like I sailed my boat, trimming and tuning them. They designed their buildings to sail in their particular climate, much as boatbuilders did for their particular waters. It is such a brilliant analogy.

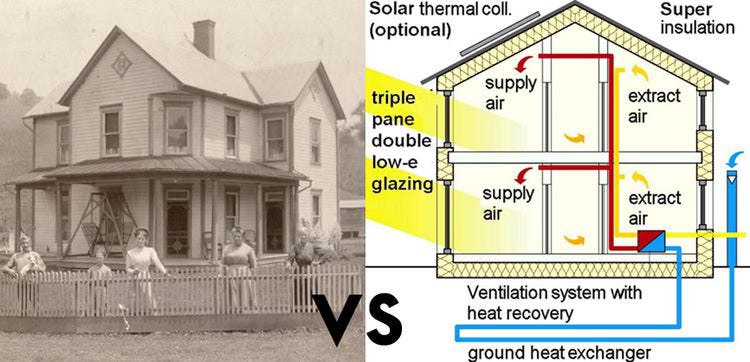

The paper, written by Bill Bordass, Robyn Pender, Katie Steele and Amy Graham, challenges many of the assumptions and concepts I have written about for years regarding building renovations and the necessary upgrading of millions of homes. There is the question of “fabric first”- do we fix the building envelopes or fabric with insulation, air sealing and new windows, or do we just do the minimum and heatpumpify it? (see Toby Cambray in Passive House +)

I have touted that Fabric remains First to minimize energy consumption, deal with resilience and intermittency, shave peak demand, and provide a comfortable, healthy environment: “Uninsulated walls and poor-quality windows significantly lower the mean radiant temperature (MRT), reducing comfort levels.” But Fabric First can be expensive and difficult. What if there is a different approach to these challenges?

MRT is the key concept here, which I learned about from engineer Robert Bean, (and also from Allison Bailes’ 2012 article, Naked People Need Building Science) Bean wrote in BCBEC Elements (page 8) about how few people understand how our bodies react to the walls around us:

“What it all boils down to is this: in winter, bad building enclosures have interior surfaces much cooler than the skin temperature and therefore extract energy via radiation from your body faster than you can internally produce it. The results: you feel cold even when the thermostat is meeting the code requirement of 22°C.”

Bean continues with a rant about architects and engineers who don’t get this:

“It has been an epic disservice to the world of architecture to use air temperature as an exclusive proxy for conditioning people when thermal radiation plays a dominant role. Once you get your head around this principle, you can appreciate how the inside surface temperatures of a room, a function of its enclosure performance, controls the rate of radiant energy exchange and thus heat loss from the human body.”

Once I got my head around this principle, I became convinced that full “fabric first” renovations were the only way to go- we want warm walls! Now, Bordass, Pender et al, who also understand MRT, turn everything completely on its head. They go medieval on the conventional wisdom, and look to history to find other ways to control the rate of radiant energy exchange. The abstract sums it up:

“To decarbonise the built environment, it is widely assumed that ‘fabric-first’ building upgrades are essential. An alternative, people-first approach is proposed that could deliver energy and carbon reductions at scale and speed. The approach begins by re-examining some rarely questioned assumptions around historical practices and building science.

The authors note that the fabric-first approach is problematic in terms of cost, timescale, and upfront carbon. It also emphasizes efficiency rather than sufficiency-how much do we really need?

“This paper explores an alternative approach to transitioning the building stock to net zero. The first part considers some crucial but often-overlooked background science, interweaving building physics with thermal physiology.”

They quote a doctor in 1916 who could have been Robert Bean in another life: “For the purposes of controlling the heating and ventilation of rooms, the thermometer has […] acquired an authority which it does not deserve.”

Instead, before the thermostat age, people “developed sophisticated methods to control how much heat was drawn from the body into the surroundings.”

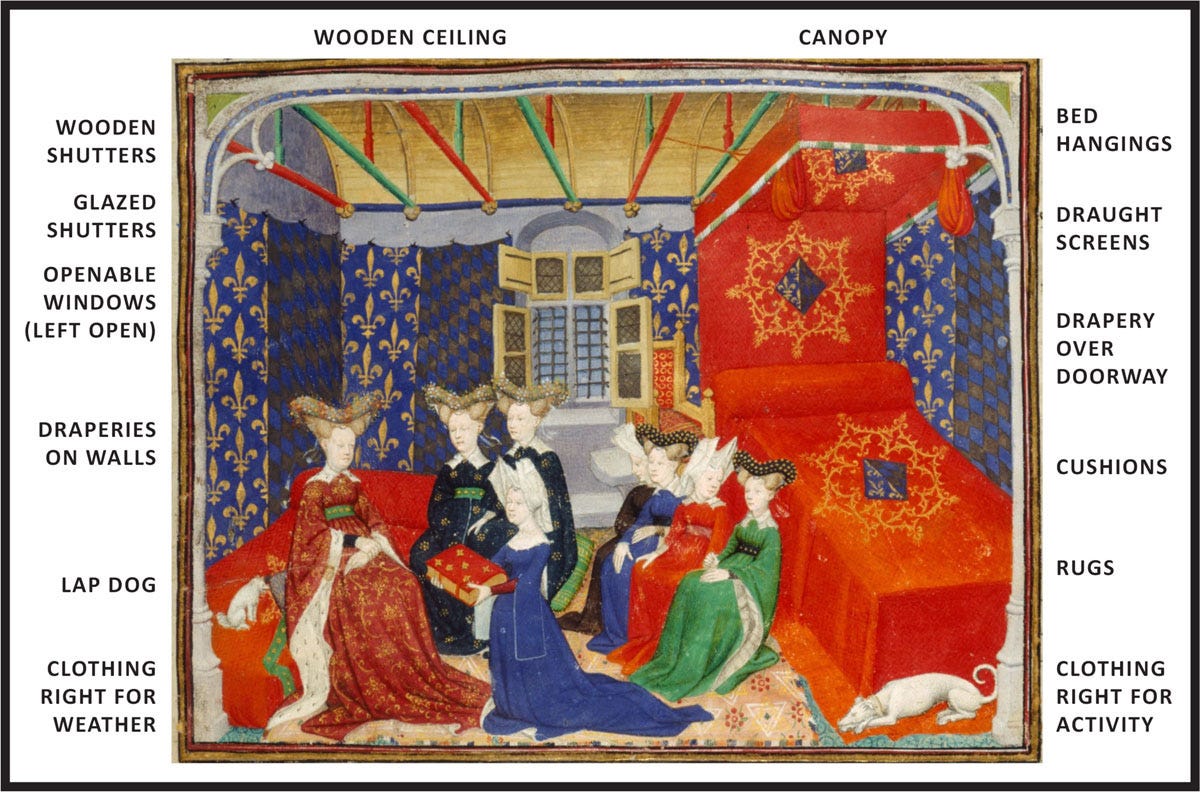

“Medieval illuminations are a goldmine of information about the pre-carbon past, showing not only climate-appropriate clothing (voluminous and layered, with soft head coverings), but also fixtures including porches, wooden ceilings, shutters and furnishings. A widespread element, still found in vernacular buildings in the Global South, is placing radiant barriers between occupants and cold surfaces nearby, most often draperies, canopies, rugs and panelling. These are commonly misinterpreted as purely decorative, but their purpose must also have been practical. Incoming radiant heat can quickly warm hangings of organic materials such as cloth and wood.”

Radiant barriers are not insulation. You wouldn’t think that hanging a sheet of fabric would make much difference, but it breaks the direct connection to the cold exterior walls. It changes the MRT. I wrote in an earlier post about how we used to live:

“Insulation barely existed, but those old walls were better than people give them credit for. Interior design kept you warm, with wing chairs and heavy drapes. But most importantly, people dressed for the season and insulated themselves.”

Add appropriate clothing and a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel on your lap (as my wife did with the late Millie), and you are set.

The authors then describe how all this knowledge was lost, starting with the Industrial Revolution and the availability of coal for heating. “With coal now relatively cheap, rich households soon installed grates in almost every room.” Also lost was the idea of “greatcoat” building thick solid walls with serious thermal mass, in favour of the layered look and its inherent moisture management issues.

The New Manual: Light, Air and Openness

This is part of a series where we develop a manual for understanding the homes we have today and what they must become – resilient in the face of change, supportive of our health and well-being. Efficient but, more importantly, sufficient – just what we need to be happy, healthy, and comfortable.

The authors note that the windows are usually open in the medieval illuminations, as they were also in the tuberculosis era after the First World War, which I have discussed in many posts about the modern movement. More recently, we have sealed everything up, leading to all kinds of problems.

“The discovery of antibiotics allowed air exchange to be restricted, and central heating and air-conditioning became increasingly popular. The first energy crisis in 1973 led to further ventilation reductions to save fuel, but increased problems of indoor air quality and mould growth.”

The authors also make a strong case that we have become habituated to controlled environments and our bodies are losing the ability to adapt.

“Recent research in thermal physiology suggests this desire for thermal neutrality can be positively unhealthy. Where people become habituated to tightly controlled environments, their thermoregulatory systems begin to shut down, making them less able to adapt to changing conditions…Medical researchers are now establishing links between insufficient exposure to wide-ranging thermal conditions and modern health issues, including obesity, high blood pressure and diabetes.”

They bring in my favourite sufficiency argument: how much thermal neutrality do we need? How tightly should we regulate temperature? They suggest “the commonly specified indoor temperature range of 21–24°C could be widened to 18–28°C by exploiting adaptive opportunities, and to 16–30°C by adding personal comfort systems such as local fans and heaters.”

The authors conclude that “thermal satisfaction can be achieved by low-cost, low-risk actions by harnessing an understanding of thermal physiology, e.g. by taking proper account of how thermal radiation and air movement affect human physiology.” We should learn from history, from how we lived before the thermostat age.

“Gary Raw, an expert in psychology and comfort at the Building Research Establishment (BRE) in the 1990s, once observed: ‘People are the best measuring instruments; they are just harder to calibrate.’ A people-centred approach to retrofit allows occupants to calibrate themselves, by paying attention to their own senses and learning to trust them. The background science and history suggests this could support the sufficiency agenda, improving occupant health whilst using considerably less upfront and operational energy and carbon.”

This is all counterintuitive, but if comfort comes from stopping heat loss or gain from our skin, to control the rate of radiant energy exchange, the authors are simply pointing out that there are alternative methods that have been known for centuries that we have forgotten how to use.

Of course, there is the question of whether people would be willing to live like this in the modern age. We have become habituated by central heating and air conditioning. In many parts of the world, they are now necessary to survive. But we certainly could use these techniques to widen the range of temperatures that we are comfortable in.

We can learn to sail again. Instead of reaching for the thermostat, we can sniff out the breeze, adapt to conditions, work with the climate instead of trying to bend it to our will, because we will eventually lose.

Ten years ago, I asked, Should We Be Building Like Grandma's House or Like Passive House? After years of promoting houses like grandma’s with large double-hung windows, high ceilings, porches, and tuning windows for maximum air flow, I concluded that climate chaos changed the picture and that we needed Passive House for both new-build and retrofit. I still believe Passive House is a no-brainer for new construction.

For retrofit, I have been solidly in the Fabric First and Passivhaus EnerPHit brigade. However, after listening to Nigel Banks on a recent Zero Ambition podcast and reading Learning to sail a building: a people-first approach to retrofit, I am wondering if we should be listening to grandma more.

I previously wrote about Robyn Pender’s work:

Nice shades: Beat the heat with awnings

When I wrote for Treehugger, I did a continuing series about “nice shades,” extolling the virtues of keeping the heat out before it got in. Some of them were fixed, and some were what Mike Eliason called “active solar protection”- operable external shading devices to eliminate solar gains and keep places cooler in summer and shoulde…

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35- US$37-the dollar is falling ). I am running out of stock, so hurry!

I’ve long wanted to write a blog post titled “Everything I Know About Architecture I Learned from Sailing.” Looks like you’re already on it Lloyd! (Of course Peter Prangnell might have played a bit of a role too. 😉) Fabric First plus Adaptive Control perhaps? Throwing technology at the problem is the architectural equivalent of what we called motorboats when I was a kid: stinkpots.

It’s nice to have a name for how we (try to) manage the temperature of our 100 year old grandma house in the okanagan valley. The single best thing we have done to manage the heat is to put up curtains and bamboo blinds away from the house to stop the walls from getting hot, and then in the winters to use draft dodgers, curtains, and storm windows. It’s not perfect, but it means we can restrict use of our portable, inefficient ac to days that reach 34C+ and nights that don’t go below 25C.

Oh, and as a cavalier owner, lovely to see the late Millie, especially as Millie is my childhood nickname.