Nice shades: Beat the heat with awnings

In a warming world, we need to bring awnings back to our homes and our streets.

When I wrote for Treehugger, I did a continuing series about “nice shades,” extolling the virtues of keeping the heat out before it got in. Some of them were fixed, and some were what Mike Eliason called “active solar protection”- operable external shading devices to eliminate solar gains and keep places cooler in summer and shoulder seasons. Mike wrote:

“Unfortunately, there is effectively no active solar protection industry in North America. Power outages will increase in the future, especially during heat waves. How will building occupants keep cool when they cannot even keep the sun out of their buildings? Operable external solar protection offers a level of climate adaptiveness that planners and policymakers need to be thinking about in a warming world.”

A hundred years ago, there was a very active solar protection industry in North America, making, installing and maintaining awnings. This was also the case in the UK; writing in Building and Conservation, Robyn Pender gives us some history (and demonstrates her understanding of Mean Radiant Temperature:)

“The need for awnings must have become obvious as soon as glass became cheap enough to allow for large areas of glazing. The Georgians quickly discovered that once a building envelope incorporates sizable areas of glass, overheating becomes a greater concern than cooling: even in winter, and even in winters in a cold climate such as the UK. Not only does the glass heat in the sun, and then radiate that heat into the room, but sunshine hitting the occupants and the surfaces around them will cause immediate discomfort, as well as fading and other degradation of organic materials such as timber and fabric.”

Pender also describes how awnings were truly active.

“The ease with which awnings could be operated must have been another reason for their popularity. Building environments are always dynamic, fluctuating with the changing seasons, the weather and the time of day, but also whenever occupants make adjustments according to their tastes or what they are doing in the space at the time.”

This is still true; the US Department of Energy confirms it:

You can also adjust your use depending on the season: keep awnings installed or closed in the summer and remove or open awnings in the winter. You can roll up adjustable or retractable awnings in the winter to let the sun warm the house. New hardware, such as lateral arms, makes the rolling up process quite easy. Some awnings can also be motorized for easy operation.

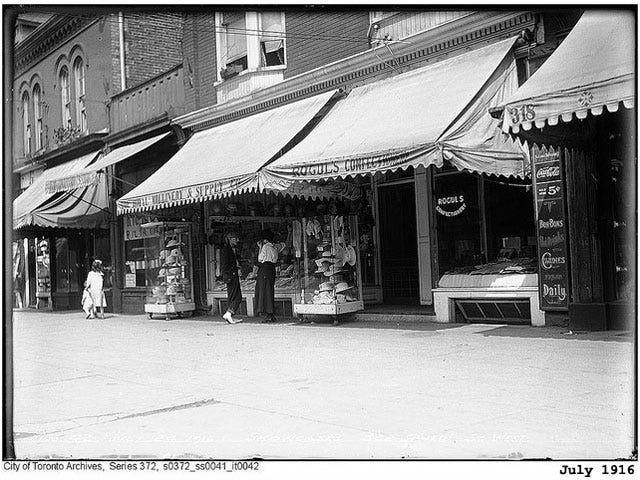

When awnings were installed over storefronts at street level, they not only protected the shops and the goods displayed on the sidewalk, but they also gave shelter to pedestrians, who could enjoy the shade as well.

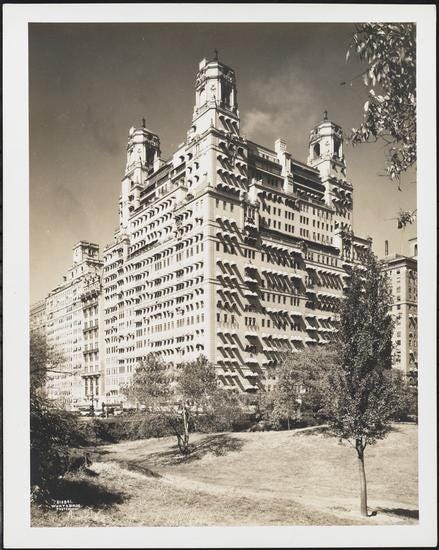

This photo of an apartment building in New York City shows how effective awnings were in shading windows.

Air conditioning eliminated most awnings; it was more effective to remove heat after it got in than it was to try and keep it out in the first place. Fiddling with a thermostat was easier than fiddling with an awning. But there is a real cost in dollars and carbon emissions when relying on air conditioning alone.

In a warming world we likely need both. The Department of Energy says “Window awnings can reduce solar heat gain in the summer by up to 65% on south-facing windows and 77% on west-facing windows.” This could significantly reduce air conditioning demand and possibly reduce the size and the cost of the AC equipment.

We also live in a world where upfront carbon matters, where we are trying to reuse and repurpose existing buildings instead of demolishing and building new. Awnings are a natural for older buildings; they may well have had them years ago. Robyn Pender writes that they could be a key part of a retrofit strategy, especially for historic buildings:

“The arguments supporting awnings on windows subject to solar gain are indeed so strong, especially in the face of climate change, that there would be a case for installing them on some listed buildings (and of course on many unlisted ones) even where there is no positive proof that they originally existed. Reinvigorating the love affair the UK once had with these practical and beautiful building elements would seem to be an obvious contribution to effective retrofit. By making the buildings much more usable, they can tick both conservation and sustainability boxes.”

But I wonder if the most important use of awnings might be to preserve and revitalize our main streets. As these hipsters hanging out on Toronto’s trendy Queen Street West demonstrate, it was the cool place to be. As our cities get hotter, shade will become more desirable and even necessary for our streets and buildings to be comfortable, inside and out.

When I designed my own home, based on some adapted Frank Lloyd Wright "Usonian" designs, I talked with a solar guy about passive solar. His recommendation, which I took, was to calculate the summer sun angle and put an overhang on the roof that would keep all sun out of the house from mid-May to the end of July, but allow full sun entry all day from mid November to February at least. It works, and works well. In winter, on a sunny day, we hardly use any heat (Virginia - Shenandoah Valley). The straw bale walls and R50 insulation in the ceiling prevent heat loss. In summer that same insulation reduces solar gain, and the shade from the overhang keeps the sun from overheating the house. We still have no air conditioning, though the impact of global heating may change that sooner than we expected. Good shade from trees as well as awnings are a great value. Awnings help more when complemented by keeping impervious surfaces cool with street trees. More trees and fewer cars complement good design.

For temperature control we could also bring back transoms and vestibules.