The New Manual: Light, Air and Openness

Part II- a look at the roots of modern architecture and fighting disease with design.

This is part of a series where we develop a manual for understanding the homes we have today and what they must become – resilient in the face of change, supportive of our health and well-being. Efficient but, more importantly, sufficient – just what we need to be happy, healthy, and comfortable.

In her book X-Ray Architecture, Beatriz Colomina writes:

“Modernity was driven by illness. The engine of modern architecture was not a heroic, functional machine working its way across the globe, but a languid, fragile body suspended outside daily life in a protective cocoon of new technologies and geometries. It is the difficulty of each breath and therefore the treasure of each breath: the melancholy of modernity.”

The illness was tuberculosis. After Robert Koch figured out that a bacillus caused Tuberculosis back in 1882, and after the First World War and the Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918, Doctors knew what caused many diseases but didn’t have the drugs to deal with them. So essentially, they and the architects of the time fought disease with design. Colomina continues:

“Nineteenth-century architecture was demonized as unhealthy, and sun, light, ventilation, exercise, roof terraces, hygiene, and whiteness were offered as means to prevent, if not cure, tuberculosis. The publicity campaign of modern architecture was organized around contemporary beliefs about tuberculosis and fears of the disease. In his book The Radiant City of 1935, Le Corbusier dismisses the "natural ground" as "dispenser of rheumatism and tuberculosis" and declares it to be "the enemy of man." He insists on detaching buildings, with the help of pilotis, from the "wet, humid, ground where disease breeds" and using the roof as a garden for sunbathing and exercise.”

In Light, Air and Openness, written in 2008, the late architectural historian Paul Overy demonstrated that many of the features of modernist classics, and much of the furniture and the trends in interior design, are a direct response to disease, and a belief in the healing power of light, air and openness.

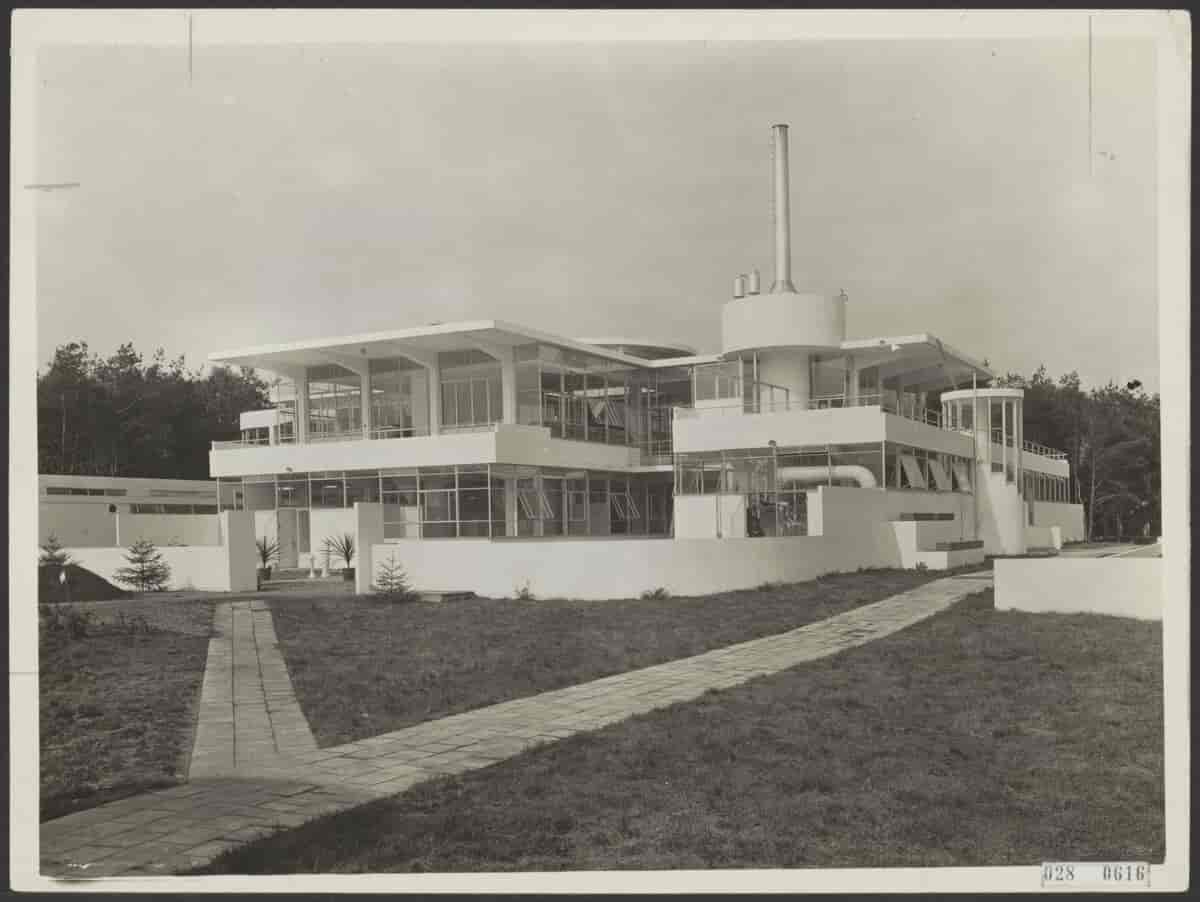

It started with the sanatorium movement, where buildings like Zonnestraal in Hilversum, the Netherlands, by Jan Duiker and Bernard Bijvoet, were designed to provide what was about the only thing that cured tuberculosis: rest, fresh air, and sunlight. Overy writes about how the design elements used in these hospital settings were transferred to homes:

Sanatoriums exerted a powerful hold on the imagination of modern architects and designers as building types and institutional models. Among the first to be designed in in “modern” or “modernist” style, purpose built sanatoriums for tuberculosis and other chronic diseases were some of the most technologically advanced buildings of the first decades of the 20th century. Combining associations of health, hygiene cleanliness (and easy-to-cleanness) modernity and machine like precision of operation, they were to have a major influence on modernist architecture and furniture design between the wars.

It was definitely a style: “The austere white rooms for the patients of sanatoriums were designed not only to be easy to clean but to appear to be spotlessly clean- potent visual symbols of hygiene and health.”

The basic rules of the hospital soon came to the home:

Dirt and dust harboured germs that must be destroyed by fresh air and sunlight. Homes should be cleaned thoroughly every day and windows and doors opened each morning to let in the sun and air, to destroy the germs. Heavy drapes and curtains, thick carpets and old furniture with decorative features that harboured dust and microbes should be thrown out and replaced with simple, easily cleaned modern furniture and light, easily washed curtains.

As noted last week, Le Corbusier preached this in his book, Towards A New Architecture:

Readers were urged to buy only practical furniture, never decorative pieces. “If you want to see bad taste, go into the houses of the rich.” Clutter was prohibited: “Keep your odds and ends in drawers or cabinets… a house is only habitable with it is full of light and air, and when the floors and walls are clear. Heavy furniture and thick carpets must be eliminated. “bear in mind economy in your actions, your household management and in your thoughts.”

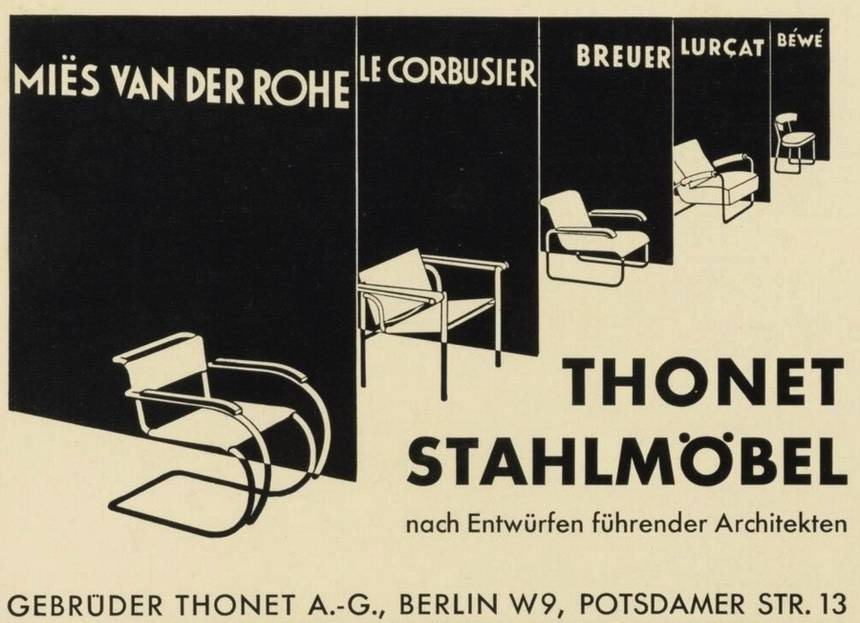

Today, we worry about dust being full of flame retardants, and overstuffed furniture being full of bedbugs; it’s not just bacteria that one can fight with minimalism. That’s why furniture changed, moving away from carved wood and upholstered chairs; “Dust containing tubules and other bacilli lodged in upholstery, in crevices, and especially in decorative features, add as regarded as a particular enemy of hygiene to be eradicated at all costs.”

So Thonet made chairs out of bentwood and cane; Aalto used bent plywood; Marcel Breuer out of tubular steel. It was all designed to be washable, light and easy to move to get at those dust bunnies lurking underneath. Mies van der Rohe wrote of one of his tubular-steel chair designs that it could be “easily moved by anyone and because of its sled-like base it can simply be pushed across the floor.”

“It therefore promotes comfortable, practical living. It facilitates the cleaning of rooms and avoids inaccessible dusty corners. It offers no hiding place for dust and insects and therefore there is no furniture that meets modern sanitary demands better than tubular-steel furniture.”

The architects and planners of the twenties and thirties were worried about tuberculosis and prescribed modernism, light, air, cleanliness and openness. They were right; architecture, planning and public policy were surprisingly effective at dealing with disease, once it was figured out what caused it; in her book The Drugs Don’t work, Professor Dame Sally Davies writes:

Almost without exception, the decline in deaths from the biggest killers at the beginning of the twentieth century predates the introduction of antimicrobial drugs for civilian use at the end of the Second World War. Just over half the decline in infections diseases had occurred before 1931. The main influences on the decline of mortality were better nutrition, improved hygiene and sanitation, and less dense housing with all helped to prevent and to reduce transmission of infectious diseases.

The pandemic has taught us that our homes and our cities are no longer protecting us; we are no longer fighting disease with design. Colomina, writing about Alvar Aalto’s Paimio sanitarium, notes that “tuberculosis helped make modern architecture modern. It is not that modern architects made modern sanatoriums. Rather, Sanatoriums modernized architects.”

Today we have COVID-19 and climate change. We have learned about PM2.5 and PFAS and other pollutants. It’s time to modernize architects again in the face of our current threats and challenges.

Next: a look at some of the early attempts at healthy houses. Previously:

DeLIGHTFUL! Thanks for the articles and information.

Healthy buildings are a treat we rarely have. Worth noting the work of the San Luis Sustainability Group, Jonathan Hammond at Indigo Architects.

One of my unfinished books is "Buildings of Comfort and Joy"

Microbiome work is the new frontier.

Thank you Lloyd for such unique take on Modern and modernity. I enjoyed reading this article and I do think we as designers have left the health of our buildings occupants squarely in the hand of medical and pharmaceutical establishment. We assume no responsibility on the issue therefore we have no authority on this issue any more. This was not historically so. I also address this issue in one of my articles here. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/architecture-health-very-brief-history-ali-heshmati/

Let me know what you think.