Why a symposium on embodied carbon gives me hope

I have been saying for years that it is not how we build, it is what we build that matters, and now I see others saying the same thing.

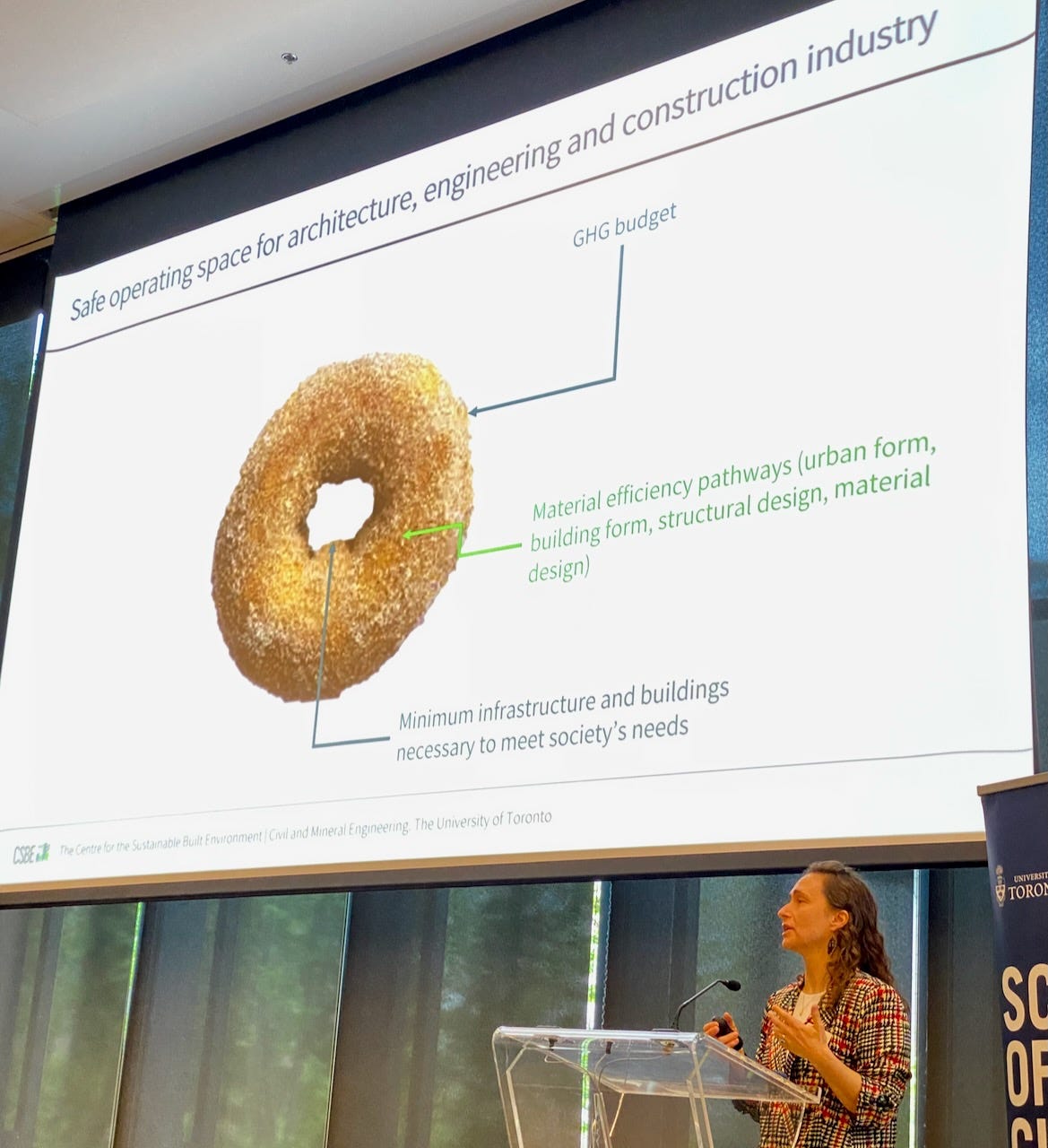

I attended most of the Embodied Greenhouse Gas Symposium on Monday morning (I had to leave at lunch to catch a train to do my own lecture that evening). Organized by the Centre for the Sustainable Built Environment, it included a presentation by Isabelle Smith about lessons learned from the UK (something I go on about all the time, they are so far ahead of us!), then Professor Shoshanna Saxe, a thought leader on embodied carbon.

Daniel Posen asked for some audience participation, and Chris Magwood and I discussed Magwood’s recent work on the embodied carbon per person for different housing types. It was all very animated and interesting.

Then there was the very exciting presentation by Keagan Rankin, a very young-looking PHD student at the University of Toronto. I am not very young, and started writing about this stuff 15 years ago for an American website with the silly name Treehugger, and much of it isn’t even online anymore. I teach a course at Toronto Metropolitan University and have written a few books, but I am not an academic, and I am not a publishing prodigy like Shoshanna Saxe.

The more Rankin spoke, the more excited I got; he put into images and words everything I have been going on about forever. It almost felt like a personal vindication, even though I doubt anyone on that team had ever read a word of mine, and probably not a word of Chris Magwood’s either, even though he was a pioneer in embodied carbon.

They have put it all into a paper; Rankin, Aldrick Arceo, Kaan Isin, and Shoshanna Saxe recently published Embodied GHG of missing middle: Residential building form and strategies for more efficient housing in the Journal of Industrial Ecology. They “look at the reduction potential of missing middle (low-rise multi-unit) housing, compare missing middle to single-family and mid/high-rise buildings, and identify opportunities for optimizing efficiency within forms.”

This has been my bread and butter for years, so I thought I would take this opportunity to do a roundup of some of my writing that survives on the web. I also discuss a lot of it in my new book, The Story of Upfront Carbon. Before the Missing Middle became common, I called it something else:

Treehugger and the defunct Planet Green may not keep posts up, but the Guardian is forever. A decade ago I was contributing to a series they were running on urban design and discussed what I called the Goldilocks Density, essentially the missing middle, “not too high, not too low, but just right.”

At the Goldilocks density, streets are a joy to walk; sun can penetrate to street level and the ground floors are often filled with cafes that spill out onto the street, where one can sit without being blown away, as often happens around towers. Yet the buildings can accommodate a lot of people: traditional Parisian districts house up to 26,000 people per sq km; Barcelona's Eixample district clocks in at an extraordinary 36,000.

More: Cities need Goldilocks housing density – not too high or low, but just right

In the photo of Rankin earlier in the post, he is comparing the embodied carbon per capita in different forms of housing in Montreal, where the Plateau district achieves remarkable densities in three stories of wood frame.

“With the exterior stairs, they are very efficient, with almost no interior space lost to circulation. Everybody wants to live there, and people raise their families there. It's just the way things are in Montreal.”

More: We Don't All Have to Live in High Rises to Get Dense Cities; We Should Just Learn From Montreal

I also have written about how they got those crazy stairs, another example of zoning and unintended consequences. Why Did Montreal Get Those Twisty Deathtrap Stairs?

In Ontario where I live, you either get ridiculous skinny towers or sprawl. But it was clear that when it comes to upfront carbon, building form and design matter more than anything else. My cry into the wilderness was:

This is why our “green” building standards are so ridiculous; As I say repeatedly, the great hypocrisy is that the single biggest factor in the carbon footprint of our cities isn't the amount of insulation in our walls; it's the zoning.

We know from the study led by H. L. Gauch, What really matters in multi-storey building design? A simultaneous sensitivity study of embodied carbon, construction cost, and operational energy that shorter, boxier, woodier, buildings have the lowest upfront and operating emissions of any building form. If these were spread over the city instead of single family houses we could avoid building super-tall buildings.

More: How tall should a building be: How not to build in a climate crisis

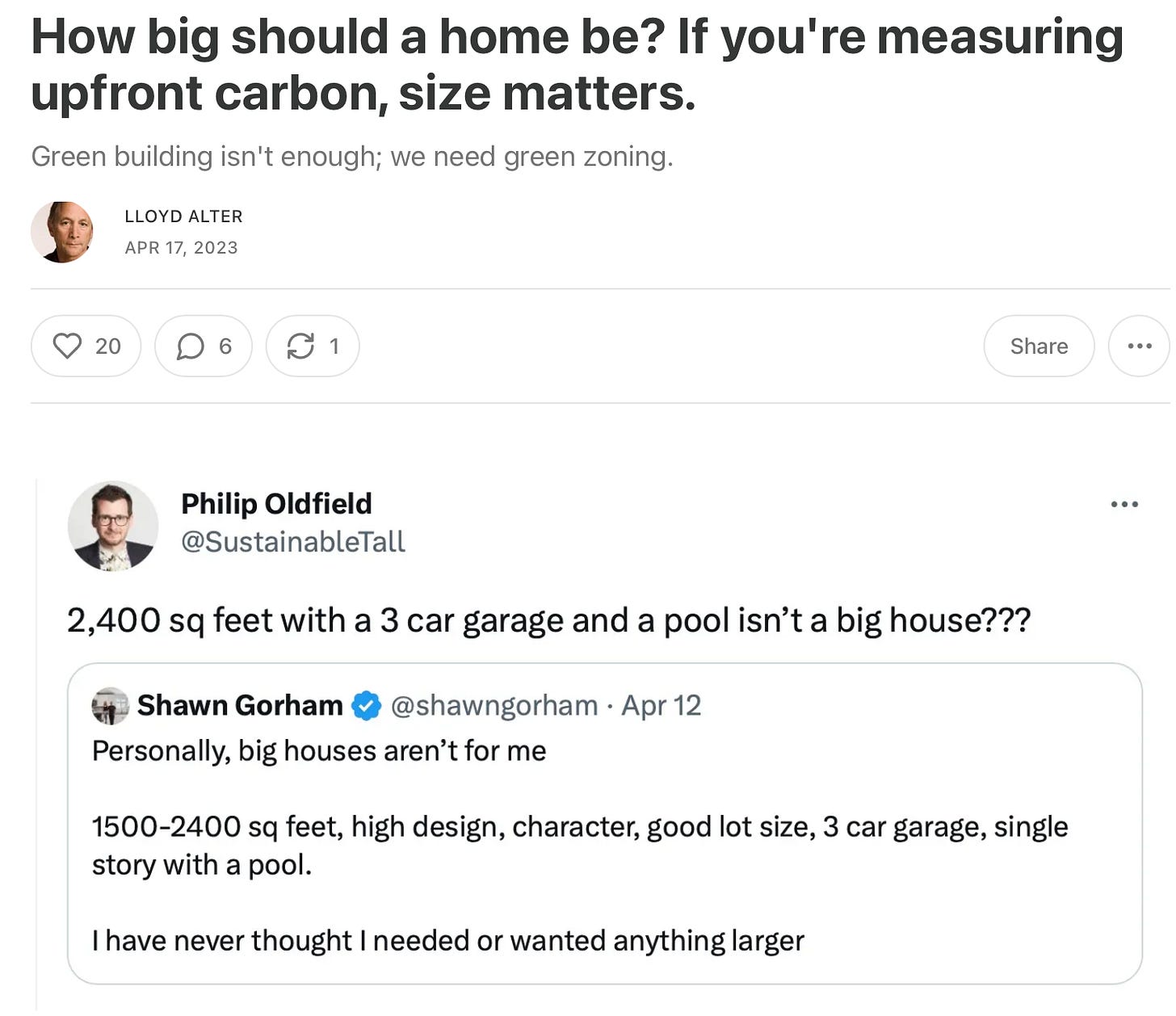

I was impressed that Rankin was talking about carbon emissions per person rather than per square meter, which most standards do. House size is often a function of building type; single-family detached houses tend to be larger than apartments because they cost less per square foot to build. But to reduce our carbon emissions, we have to build smaller and simpler.

“One could go even further and suggest that we shouldn’t be building single-family houses at all, but instead, we should live in little apartment buildings as they do here in Munich. This is the way you get the density needed to support shops, services and transit so that you can live without a three-car garage.”

More: How big should a home be? If you're measuring upfront carbon, size matters.

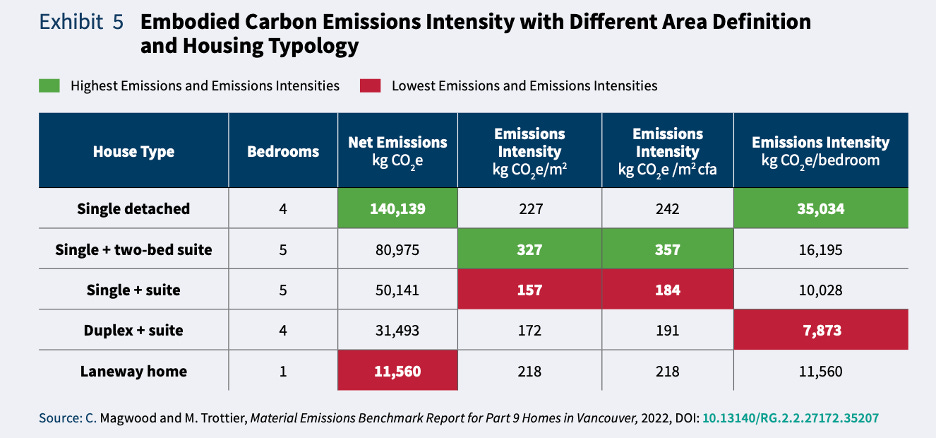

I recently wrote for Green Building Advisor about Chris Magwood’s latest research with RMI. He writes about building forms and materials:

“In addition to material substitutions, designers can deploy more material-efficient actions, such as simplifying forms, minimizing below-grade space, minimizing uninhabitable floor area, reducing or eliminating concrete floor slabs, and considering multi-unit homes that require less overall insulation and use structural systems more efficiently.”

In fact, the numbers in this table are stunning: the emissions of a single-detached home are many times greater than those of any other housing type. If you measure emissions intensity in kilograms of CO2 per bedroom, they are 4.45 times as high in a single detached house than they are in a duplex with a suite. It’s apparent from this chart that what we build has far more impact than what we build it out of.

More: HomebuildersCAN: A Prologue

One of the problems of just being a blogger on a site named Treehugger is that my stuff could go up and sink without very many people reading it. There was a lot of talk in the session about the impacts of infrastructure and transportation, and in what I thought was one of my more important posts, I suggested that we have to stop thinking of them as separate things. I don’t even think we should talk about construction emissions; they are all one thing, built environment emissions.

Jarrett Walker nailed this years ago when Twitter was useful. “What we design and build determines how we get around (and vice versa) and you cannot separate the two. They are all Built Environment Emissions, and we have to deal with them together.”

Someone should do a study on this. More: Transport and Building Emissions Are Not Separate—They Are 'Built Environment Emissions'

There is so much in Rankin’s talk that I loved. I found it hilarious that he even mentioned Ephemeralization and Bucky Fuller. I write about this in my new book and excerpted a bit:

Ephemeralization is all about going back to first principles and redesigning our world to this new paradigm where we consume fewer resources and less energy, thinking like Bucky did. Perhaps two wheels are better than four, perhaps five volts DC is better than 120 volts AC, and perhaps we no longer need so many duplicated spaces for living and working. Actually, Bucky Fuller had something to say about that too:

“Our beds are empty two-thirds of the time. Our living rooms are empty seven-eighths of the time. Our office buildings are empty one-half of the time. It’s time we gave this some thought.”

More: Ephemerality: Another radical design concept for the climate revolution

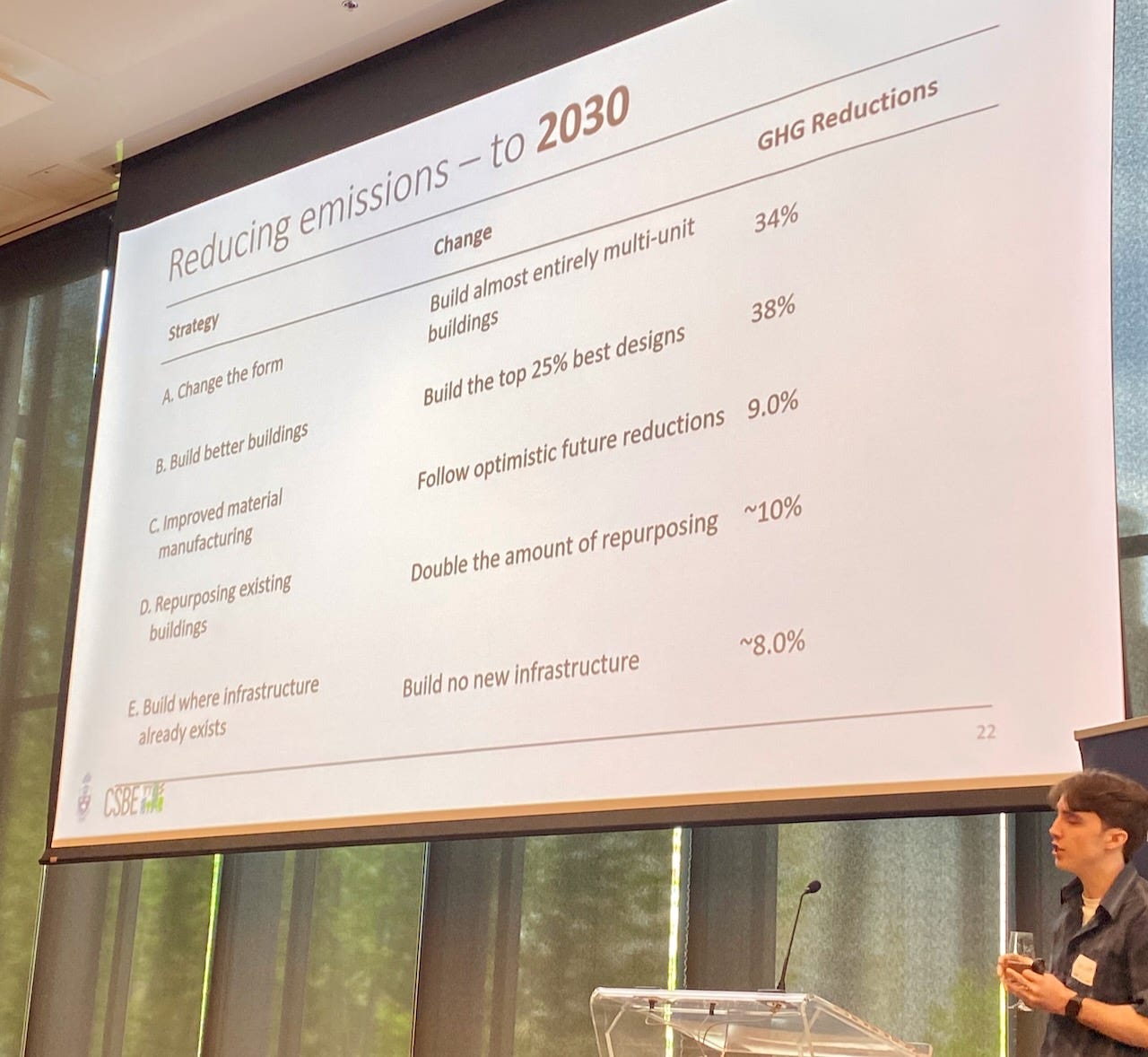

This is the slide that excited me the most. I am between 40 and 50 years older than Keagan Rankin, approaching the end of my career, I do not have a huge media platform anymore and it never was part of the academic or professional world. I am obviously not alone; I have glommed on to Kelly Alvarez Doran and Will Arnold in the UK who are talking about these issues too, but:

Everything I have been writing about for years is in those first two numbers,

A: change the form and

B: Build better buildings, where I talk about simplicity and sufficiency and satiety.

The media and the profession spend all their space on C: Improved material manufacturing, on steel and concrete, but 72% of possible reductions come from form, use, and design.

I will talk a little more about form and design in my next post, but meanwhile, thank you, Shoshana Saxe and Keagan Rankin and everyone at the Centre for the Sustainable Built Environment. I cannot tell you how wonderful it felt to see this.

I too have been lucky to have discovered your writing over the last decade. You have a knack for navigating all the technical jargon in these reports and symposiums, and then presenting it to all us laypeople. This discussion is so important right now, especially w/ the right wing factions in North America ginning up fear over "Davos Elites" and "The Great Reset." Any trivial mention of single family homes being a problem will trigger them and they'll go right to a vision of Soviet style concrete high rises. OTOH, my best clients, who are now proud owners of two 6000 sq. ft. homes 2000 miles apart, have now come to the realization (climate change isn't on their radar), that its too damn much work and that they'd be better of if one of them was a 2400 sq ft. condo! go figure

>>”and perhaps we no longer need so many duplicated spaces for living and working.”

Perhaps, perhaps not. I live with my girlfriend in a 1094 sq ft SFD tract home in a suburb of Phoenix. It has excellent flow design, no wasted space, but it’s inadequate for us as a couple and we’re looking to move into something bigger with an extra bedroom and a MUCH larger outdoor area. Part of that is due to our need for privacy to make phone calls or to watch different TV programs without disturbing the other, and partly due to a need for more space when entertaining (and gardening.)

I’m not sure how you reconstruct cities from the ground up to mimic European architecture but if you do it’s going to cost so much more in upfront carbon emissions than what can be saved—and then you will need to convince Americans to adopt communal space as their living rooms, when it’s not been part of our culture. That would also be a big hurdle to overcome.