We should rethink the toilet from first principles

It was a mistake from the day it came into our homes.

I know, I am spending a lot of time in the bathroom, having written about bathtubs, showers, sinks, bidets, and why toilets should be in their own room. This is, I promise, the last the second last, before I end with the bathroom of the future. This post is very much about the past, about how we got toilets in the first place, and why it was a fundamental system design error. Much of it is from a book I started to write about the bathroom a decade ago, an old article I wrote for the Guardian, and an earlier post.

It’s hard to find something that we actually got right in the modern bathroom. We mix up all our bodily functions in a machine designed for the benefit and convenience of plumbers, not people. The bathroom is where we interact with water and generate our waste, but it doesn’t exist in isolation. It is part of a much larger system of water supply and waste removal sewers that Victor Hugo described as “the conscience of the city. Everything there converges and confronts everything else.”

It has not changed much since Victor Hugo’s day. In fact, one could say that the North American development industry is built on shit. Basically, you either have ultra-low density development based on septic systems or you have development driven by the sewer system- the municipal responsibility of collecting shit and processing it and getting rid of it.

It’s one of the greatest misallocation of resources in history, with vast quantities of expensively cleaned and pumped water being contaminated with human waste. How we got here is a story that starts in London.

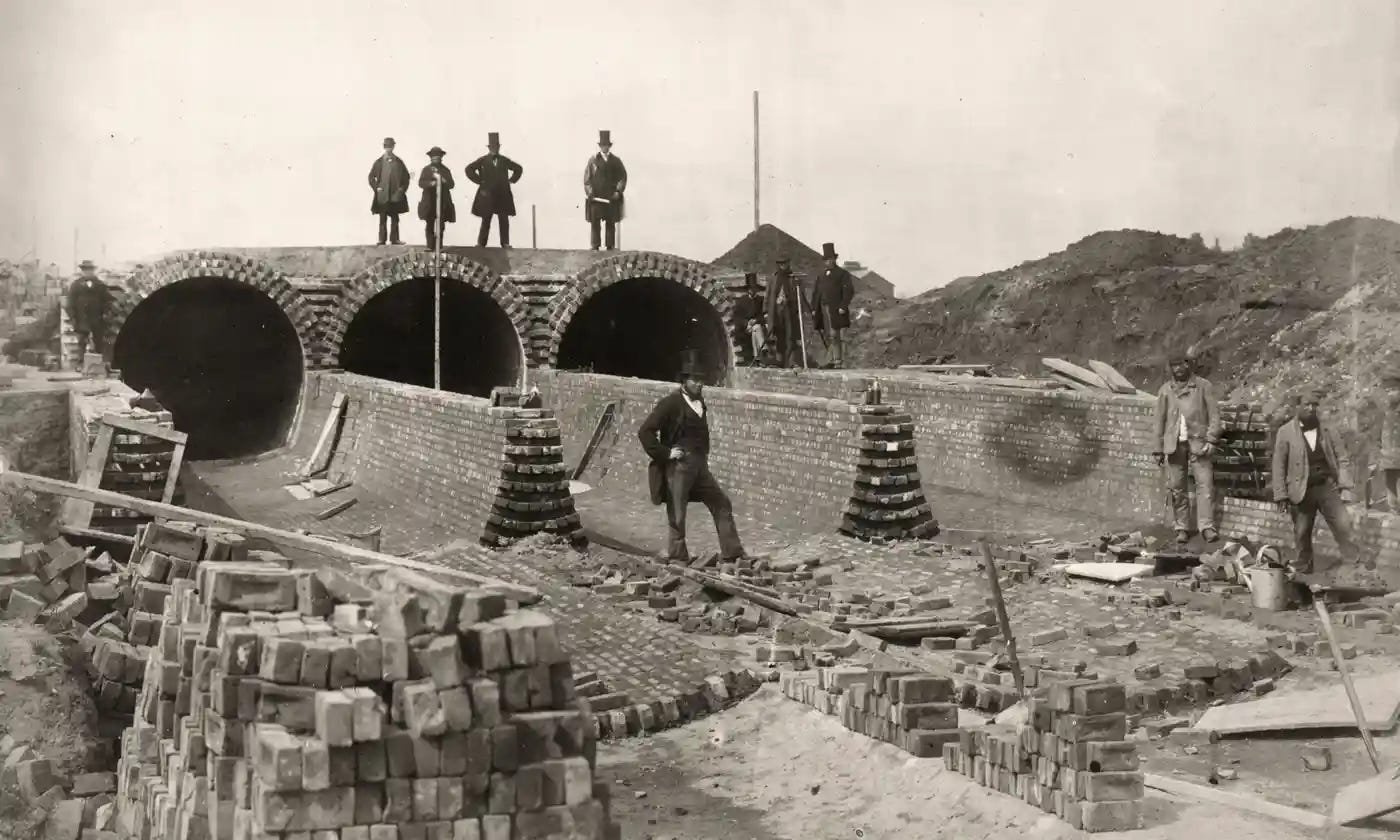

While there was some piped water earlier in the 19th century in London, the story really starts on the 7th of September, 1854, when Dr John Snow removed the handle of the pump at 37 Broad Street in London, and almost instantly ended a major cholera epidemic caused by a leaking cesspit. Until then, most Londoners got their cooking and washing water from pumps and wells, limiting their consumption to pretty much what they could carry. They dumped their waste into brick-lined cesspits that would be emptied by the night soil men, who sold it as fertilizer or dumped it off Dung Pier into the Thames. Liquid waste might be dumped into gutters in the middle of the road.

After people realized that John Snow was right, and that shit + drinking water = death, it didn’t take long for the city fathers to take the easy way out: if you cannot rely on wells anymore, pipe in fresh water from afar. Why stop pollution of your water source when it is easier just to bring it from somewhere else?

This was perhaps the greatest convenience ever known. Instead of carrying water, suddenly everyone had all the water they could use, all the time, with the turn of a tap in their kitchen. Not surprisingly, according to Abby Rockefeller in Civilization and Sludge, the average water use per person went quickly from 3 gallons of water per person to 30 and even a hundred gallons per person.

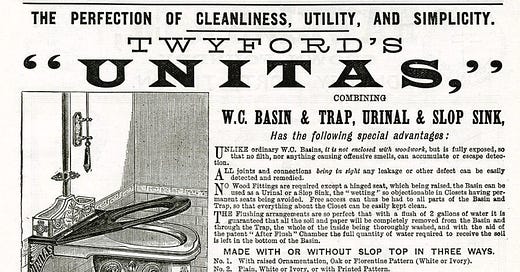

The toilet was an almost trivial addition; it had been known about since Roman times but was pretty useless without a water supply. Now it was oh, so convenient to just to wash the poop away. Except there was more poopy water than anyone knew what to do with, overflowing the cesspits and flowing into the gutters and ditches originally designed for rainwater that all led to the Thames. The result was even more cholera and disease.

The environmentalists of the day tried to stop this; they promoted earth toilets that would keep human waste separate, that would treat it as a resource. Rockefeller writes:

“The engineers were divided again between those who believed in the value of human excreta to agriculture and those who did not. The believers argued in favour of "sewage farming," the practice of irrigating neighbouring farms with municipal sewage. The second group, arguing that "running water purifies itself" (the more current slogan among sanitary engineers: "the solution to pollution is dilution"), argued for piping sewage into lakes, rivers, and oceans.”

But they never really had a chance to debate the issue; it was a done deal as people rushed to install convenient flush toilets. Soon every contaminated stream and gutter was being enlarged and covered over and turned into what remains today’s urban sewer system. Abby Rockefeller notes:

“In the United States, the engineers who argued for direct disposal into water had, by the turn of the 19th century, won this debate. By 1909, untold miles of rivers had been turned functionally into open sewers, and 25,000 miles of sewer pipes had been laid to take the sewage to those rivers."In North America, many cities were built next to rivers and oceans, so dumping sewage into them was even easier and more convenient.”

Nobody seriously paused to think about the different bathroom functions and their needs; they just took the position that if water comes in and water goes out, it is all pretty much the same and should be in the same room. In North America where most bathrooms went into new construction, it was often a tiny room; tile and plumbing are expensive.

Nobody thought about how the water from a shower or tub (gray water) is different from the water from a toilet (black water); it all just went down the same drain which connected to the same sewer pipe that gathered the rainwater from the streets, and carried it away to be dumped in the river or lake.

In other countries, the business of managing waste was sophisticated and competitive. In Japan, the value of your nightsoil varied according to wealth; rich people had better diets and made better quality fertilizer. With their more intensive farming techniques and fewer farm animals, they needed a lot of shit. Susan Haney writes in Urban Sanitation in Preindustrial Japan:

The value of human wastes was so high that the rights of ownership to its components were assigned to different parties. In Osaka the rights to fecal matter from the occupants of a dwelling belonged to the owner of the building whereas the urine belonged to the tenants. …Fights broke out over collection rights and prices. In the summer of 1724, two groups of villages from the Yamazaki and Takatsuki areas fought over the rights to collect night soil from various parts of the city.

People would even steal it. The price was so high that poorer farmers had difficulty in obtaining sufficient fertilizer, and incidents of theft began to appear in the records, despite the fact that going to prison if discovered was a real risk.

In China, they said "Treasure Nightsoil As If It Were Gold."

But technology evolved in the tanning and explosives industry and urine was no longer needed; the Haber-Bosch process gave us cheap fertilizer, replacing manure and human waste. Phosphorus could be dug out of the ground. In Japan, the Americans running the country after the Second World War were appalled by the Japanese system and insisted on its “modernization.”

The volumes of wastewater generated in our modern lives is extraordinary, and so much of it could be used in gardens, or filtered for reuse in washing, if it wasn’t contaminated by shit when we mix it altogether in our houses. Then we pipe it to the street, where in most older cities it mixes with rainwater and industrial wastewater that used to run straight into our rivers and lakes. It’s now often intercepted and expensively treated, using lots of energy and generating vast quantities of sludge that is burned, landfilled or spread on farms as fertilizer for growing mostly animal feed.

Years ago I did a press tour in Ecuador and visited Yasuni communities on the Napo River. The government had invested millions in providing modern toilets throughout the country, much like this one. The problem is, they just dumped it out into a lagoon in the forest behind, causing all kinds of problems with wildlife, and only worked when the water was running, which was only when the electricity worked and could operate the pumps. Very soon, everyone was back to the traditional outhouses and privies.

This is the fundamental problem with the toilet as we know it; It is convenient but it is fundamentally one of the most wasteful and extravagant concepts ever developed. On its own, it is just a piece of porcelain, but it cannot exist in isolation. It contaminates vast amounts of water and requires a huge support infrastructure that is going to be increasingly difficult to maintain.

In the USA, according to Chelsea Wald, “Discharge from sewage and septic systems still contributes a substantial amount to nutrient pollution, which the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) calls “one of America’s most widespread, costly and challenging environmental problems.” In some places, such as northern Florida and Cape Cod, it’s the main source of that pollution.” In the UK, according to the Guardian, “more than 384,000 discharges of raw sewage were reported by water companies across England and Wales in 2022.”

It wastes valuable nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers that are going to be increasingly hard to make or dig up. There must be a better way.

NEXT WEEK: The future of the toilet and the bathroom.

I’ve personally tried to make the mental shift to living in a spacecraft where energy supply is the principal challenge, units of energy become the basic unit of exchange and life support is a closed system.

Superb