The Canadian connections and parallels to the UK drinking water crisis

This is what happens when you privatize, cut “red tape” and eliminate oversight: things cost more and don’t work as well, and sometimes people die.

Comments have been turned off because I am tired of being called a commie and after writing this post I think it might be true. I repost on Linkedin and comments can be left there.

Forgive me for writing yet another post about the UK, but I think I did more things and met more people in three weeks there than I have in the last three plague years in Toronto. They are having a water crisis in the UK right now, as the rates for water go through the roof, millions of litres are leaking from Victorian era pipes, and shit is floating in rivers and the oceans as the sewage treatment facilities overflow on a regular basis. The biggest, oldest and most important system, Thames Water, is on the verge of insolvency.

There are a number of Canadian connections here, and there are certainly a lot of parallels to what has happened in Ontario, and there are lessons to be learned. The silliest Canadian connection happened when The Guardian wrote about how red flags were going up on the beaches in Scarborough, North Yorkshire, and had to run a correction notice: “This article was amended on 18 June 2023 to remove an image of a water treatment plant in Scarborough, Toronto, which was published in error.” That would be the R.C. Harris water treatment plant, shown above. R.C. will show up again in this post.

The history of Thames Water is particularly relevant. I have written about this in the plumbing section of a book that I never got around to finishing, the New Manual of the Dwelling. An excerpt:

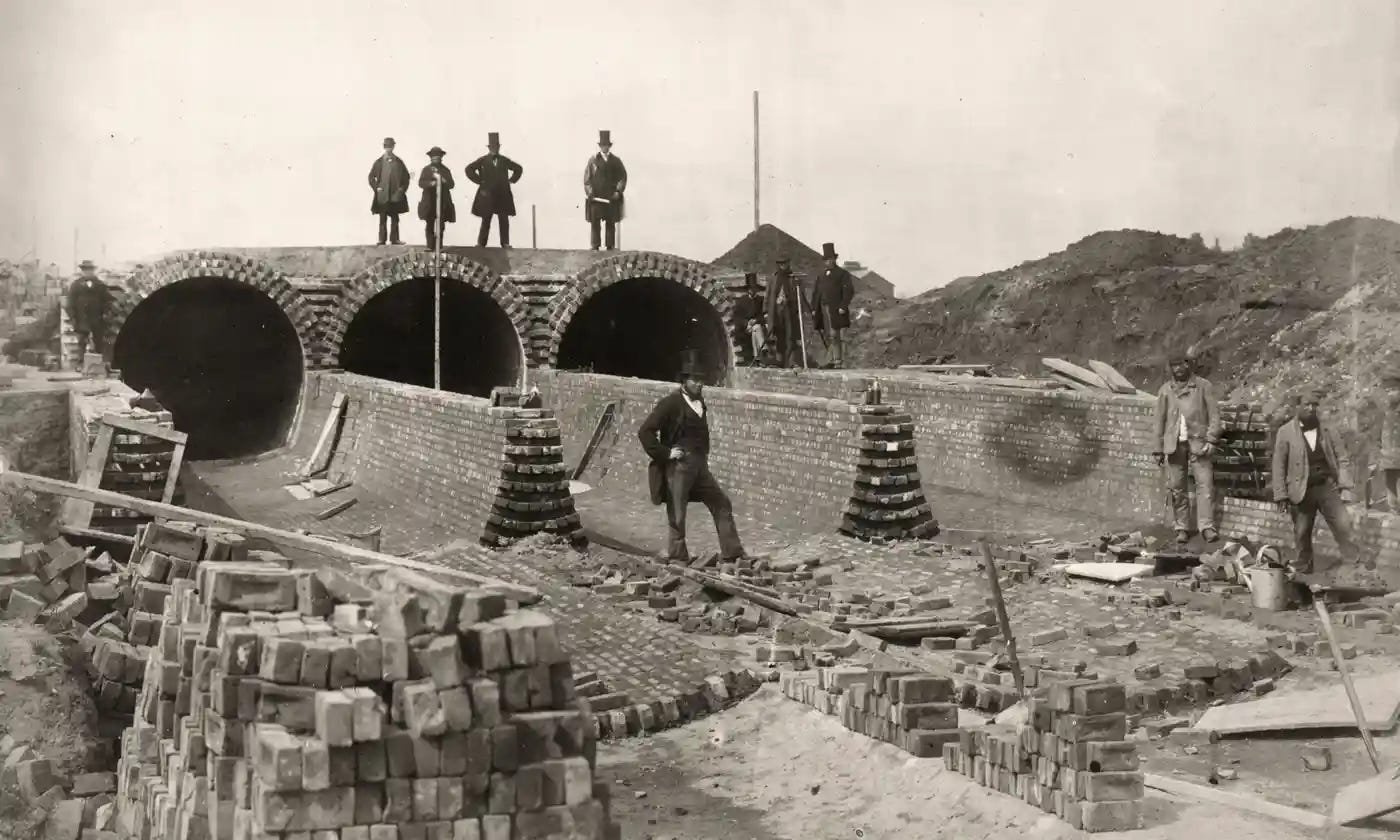

While there was some piped water earlier in the 19th century in London, the story really starts on the 7th of September, 1854, when Dr John Snow removed the handle of the pump at 37 Broad Street in London, and almost instantly ended a major cholera epidemic. Until then, most Londoners got their cooking and washing water from wells, limiting their consumption to pretty much what they could carry. They dumped their waste into brick-lined cesspits that would be emptied by the night soil men, who sold it as fertilizer or dumped it off Dung Pier into the Thames. Liquid waste might be dumped into gutters in the middle of the road.

After people realized that shit + drinking water = death, It didn’t take long for the city fathers to take the easy way out: if you cannot rely on wells anymore, pipe in fresh water from afar. Why stop pollution of your water source when it is easier just to bring it from somewhere else?

This was perhaps the greatest convenience ever known. Instead of carrying water, suddenly everyone had all the water they could use, all the time, with the turn of a tap. Not surprisingly, according to Abby Rockefeller in Civilization and Sludge, the average water use per person went quickly from 3 gallons of water per person to 30 and even a hundred gallons per person.

The toilet was an almost trivial addition; it had been known about since Roman times but was pretty useless without a water supply. Now it was oh, so convenient to just to wash the poop away. Except now there was more poopy water than anyone knew what to do with, overflowing the cesspits and flowing into the gutters and sewers originally designed for rainwater that all led to the Thames. The result was even more cholera and disease, and the “great stink” of 1858 that even closed Parliament.

The environmentalists of the day tried to stop this; they promoted earth toilets that would keep human waste separate, that would treat it as a resource. Rockefeller writes:

“The engineers were divided again between those who believed in the value of human excreta to agriculture and those who did not. The believers argued in favour of "sewage farming," the practice of irrigating neighbouring farms with municipal sewage. The second group, arguing that "running water purifies itself" (the more current slogan among sanitary engineers: "the solution to pollution is dilution"), argued for piping sewage into lakes, rivers, and oceans.”

But they never really had a chance to debate the issue; it was a done deal as people rushed to install convenient flush toilets. Soon every contaminated stream and gutter was being enlarged and covered to handle this so it could be dumped into the Thames. To intercept it all and move it downstream, Engineer Joseph Bazalgette built the massive sewer system along the embankment, over-engineering the giant pipes by 50% to accommodate a growing population; they still do the job. In the Guardian, Blake Morrison described the huge public project as being “on a par, aesthetically, with the canal bridges and railway viaducts of the Victorian era.” But it was really just going with the flow and coping with circumstance instead of thinking about the alternatives or the consequences.

The nine private water companies serving London were nationalized in 1904 and combined with the management of sewage in the Thames Water Authority, which was privatized by Margaret Thatcher in 1989, giving us the privately owned Thames Water. According to Kate Bayliss of the University of London, this was supposed to bring “fresh finance and innovation to create efficiency.” Instead, it brought debt.

“Newly privatised water companies had started out with zero debt in 1989. Yet by the end of March 2022, total debt in the sector was at £60.6 billion. In part, the increased debt was used to refinance the companies so that investors could repay themselves part of the original cost of buying the water utility.”

Here is the biggest Canadian connection: The biggest investor at 31.77% is OMERS, the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, serving half a million municipal employees who must be wondering at the irony of investing in a privatized company that used to be run by municipal employees, and has been run into the ground by people who put profit before pipes. Many of these municipal employees run efficient, safe publicly owned water and waste systems that do not fill Ontario rivers and lakes with shit and leak billions of litres of water from rusty old pipes.

Toronto also had its own Bazalgette in R.C. Harris, who lost a son to a strep infection. Jon Lorinc writes in Spacing:

“Little Emerson Harris, in short, had become a statistic in a public health catastrophe afflicting the city’s residents. In 1910, Toronto’s infant mortality rate was a staggering 140 deaths per thousand live births — an indictment of the city’s failure to provide sanitary conditions for its residents. Many Torontonians lived in fetid slums with over- flowing outhouses and open sewers.”

Harris cleaned up the city, demolishing outhouses and building sewers, with his vision culminating in the water treatment plant- “It is proposed to erect handsome buildings, which, in conjunction with the park section and the beach, would constitute one of the most beautiful areas in Toronto,” he wrote. “There will be room for a fair-sized park, and the grounds lend themselves admirably to a very fine layout, so that the new plant and park may be made exceedingly attractive.”

As Bazalgette did in London, Harris made it much bigger than needed at the time, three times as big; it was one of three facilities, and Harris was worried that there might be another war where the Germans bombed Toronto. He wanted to ensure that two of the three treatment plants could be knocked out but people would still have water. Today they are still big enough to serve not only Toronto but many of the surrounding communities. They are still public, and they are still well-run by municipal employees who care; Years ago when I rowed my single scull out of Hanlan’s Boat Club in Toronto, my oarlock broke and I tumbled into Lake Ontario. Coach Gary, who worked on water quality for the city, came up in his outboard tinny to rescue me, but his first words were “Don’t worry Lloyd, the coliform count is only 24!”

Ontario has had its own brush with privatization. Around the time Thatcher was selling off the water systems, Ontario Premier Mike Harris passed the “water and sewage services improvement act” which shut down water testing labs, downloaded control of water and sewage facilities to the municipalities, and ended the drinking water surveillance program.

In Walkerton Ontario, in May 2000, people started getting sick due to e.coli in the drinking water. 7 died at the time; they continue to die from renal failure. The investigation noted that along with the incompetent operators, the “Ontario government of Mike Harris was also blamed for not regulating water quality and not enforcing the guidelines that had been in place. The water testing had been privatized in October 1996” Ulli Deimer, a resident of Walkerton, wrote:

“The Walkerton story is the story of how systems which were established to protect public health were deliberately dismantled by a government driven by a fanatical hatred of the public sector. In the name of eliminating "environmental red tape," a water protection system designed with multiple safeguards to protect against a failure at any one point or by any one person was undermined until it could no longer function, despite the clearest possible warnings of the foreseeable consequences.”

This is what is happening today under conservative governments in the UK and Ontario. It is what happened at Grenfell. This is what happens when you privatize public services and cut “red tape” and eliminate oversight: things cost more and don’t work as well, and sometimes people die. It keeps happening and we never learn.