Everyone in the building industry must read "Show Me the Bodies: How We Let Grenfell Happen"

This isn't a UK story, it's universal.

Note: posts will be erratic for the next three weeks as I take time off for research for my book and a bit of a vacation.

If you ask most people in the building world why 72 died in the fire at the Grenfell Tower on 14 June 2017, the answer will likely be either "combustible cladding" or the "single stair." Most people in North America will not pay much attention because "it can't happen here." But the story is far more complicated. It can happen here because it was due to failures by people who were corrupt, greedy, incompetent and in over their heads, and that happens everywhere. But, unfortunately, it also appears that the wrong lessons are being learned from it.

This is why everyone in the industry should read Peter Apps' book "Show Me the Bodies: How We Let Grenfell Happen." I should note first that I have been obsessed with this story, finally reviewing the book now after reading Simon Jones’ review in Passivehouse Plus and finding I am not alone in my obsession.

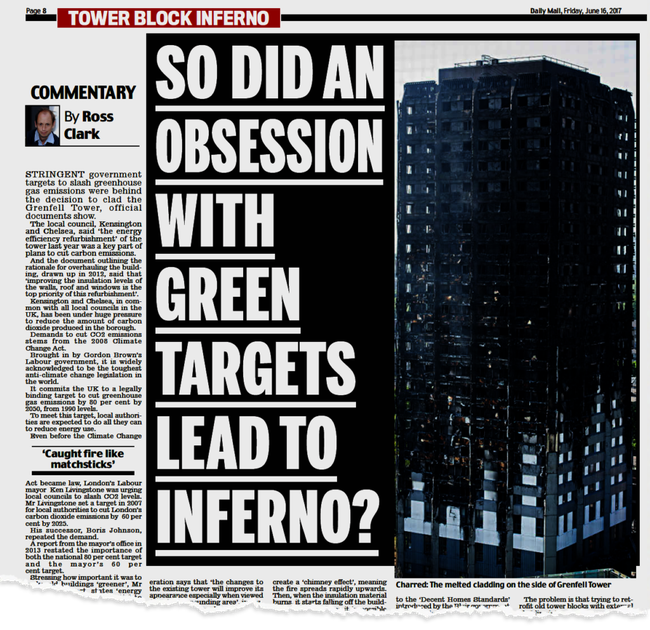

I first wrote about the fire three days after it occurred, outraged by the Daily Mail headline, which blamed it on "misguided climate change targets." I wrote that it was not about green targets but was "an indictment of plastic and foam in construction." I also worried about the effect it would have on wood construction:

"People are already circling on this. Heavy timber and cross-laminated timber do not burn like plastics; they char and take hours, not minutes to catch. The buildings made of it are usually sprinklered. It is not the same thing, but I guarantee that the concrete and masonry people are already composing their advertisements."

I also wrote about the principle of compartmentalization, where people are advised to stay in their apartments until the fire is put out. That's why single-stair designs were permitted in tall buildings. It usually works, but as Mark Coles, head of Technical Regulations at the Institution of Engineering and Technology, explained in the Engineer:

"The intent at the design stage of this building was such that the staircases were not intended to be used as a mass escape route. The advice given to residents was that, in the event of a fire, the occupants should remain in their properties. The speed at which this fire spread would suggest that there has been a serious failure in the design and installation techniques employed."

So what was the reaction of the government and the authorities to all of this? What have they done? They have essentially destroyed wood construction in the UK, even though no wood was involved, and demanded the removal of combustible cladding (including wood) on every building at significant cost to residents, ruining lives, even when the building is low-rise with balconies. And every discussion that architect Michael Eliason and other promoters of single-stair point block designs have starts with the question: "What about Grenfell?" when even the UK fire chiefs think they are fine up to seven stories.

This is a long-winded introduction to the book, where Peter Apps makes it clear that the problems lie far deeper and won't be solved by a few design changes. Apps notes that one of the first causes of the disaster starts right at the top: with Prime Minister David Cameron and his push for deregulation.

"In January 2012, he gave a speech. ‘This coalition has a clear New Year’s resolution: to kill off the health and safety culture for good,’ he said. He pledged to ‘wage war against the excessive health and safety culture that has become an albatross around the neck of British businesses’….Eric Pickles wrote to David Cameron, setting out his plans for deregulation. He included the fire safety provisions of building regulations, promising to save businesses £25.4m per year by cutting rules.”

Then there is the design team. Architect Bruce Sounes of Studio E had never done a residential cladding project, working mostly on educational buildings. He specified non-combustible zinc cladding.

But the building was over budget, and then came the inevitable Value Engineering exercise, and Aluminum Composite material (ACM) was proposed and accepted as an alternative. The cladding manufacturers knew the stuff was flammable but said it wasn’t. The insulation behind the panel was Celotex polyisocyanurate rigid insulation, also sold as non-combustible. Apps writes:

“An employee at one insulation manufacturer described a fire test on a system containing its product as ‘a raging inferno’ in 2007, but buried the testing and marketed it specifically for use on high-rise buildings. When its fire performance was questioned, one manager said those raising issues could ‘go fuck themselves’. Senior figures at a cladding manufacturer exchanged emails internally saying the company was ‘in the “know”’ about its product’s poor performance, but told its salespeople to keep its true fire performance ‘VERY CONFIDENTIAL!!!!!’. And one internal document speculates about the commercial consequences of a fire in a tower block clad with its product killing ‘60/70 persons’. Both those materials would end up on Grenfell Tower.”

Sounes may not have had much experience, but he was all consulted up, with cladding consultants and fire consultants who never even opened reports because they thought it was another consultant’s responsibility.

Then there is the construction phase, which doesn’t go much better than the design phase. Fire stops and barriers, poorly designed, to begin with, are then poorly installed.

“Cavity barriers were installed upside down, vertically when they should have been horizontal, in the wrong place and cut to the wrong shape. A member of staff at the supplier of the barriers would later call it some of the worst work he’d ever seen.”

So when a fridge on the fourth floor caught fire on 14 June 2017, and flames got out through the vinyl window, it wasn’t stopped by cavity barriers but shot up as if in a chimney. the ACM’s polyethylene core melted and burned hot enough to ignite the insulation. The fire spread up and melted the vinyl window frames of other units, filling them with toxic smoke and carbon monoxide.

Meanwhile, the fire department told everyone to stay inside their apartments for 80 minutes, by which time most of them were dead. But the stairway! Apps writes:

“There is also the single staircase. This issue is sometimes overstated. One expert analysed the staircase and found that in normal conditions it was wide enough to accommodate the entire 293-person population of the tower, even if they entered simultaneously. The time it would have taken for an able-bodied person to descend under normal conditions from the very top of the tower was four minutes. This shows us the extraordinary difference a decision to evacuate the building before the stairwell became smoke-logged might have made.”

However, Apps acknowledges that a second stair would have been useful; the firefighters clogged the stairway, and their hoses kept stairway fire doors open so it filled with smoke. This is was a tall building; most single-stair buildings are low enough that ladders can reach apartments from the outside and pick people off balconies, which is what all single-stair advocates propose. But the real issue was not the lack of a second stair, it was the failure to evacuate.

Apps concludes:

“The world that gave us the Grenfell Tower fire looks irredeemably dishonest. It is a story of corporate structures that allowed human beings to abandon their own conscience and sense of agency and to think only about sales and profit margins. Government institutions placed ideology above human lives at every turn.”

And none of that has changed at all. Instead, we get knee-jerk reactions like banning wood and blaming the architect. This was all disturbingly familiar and one of the reasons I was so glued to this story; As I noted in my post about the inquiry,

“I thought I had a pretty good idea of what went wrong; I chose the same cladding for the last project I did as an architect – a job that was too big for me to handle, which I got because I proposed a fee too low to do it properly, that had too many consultants working at cross-purposes, for a client who kept changing everything as it went along.”

It’s not just the obvious issue with the cladding, it’s not the stairs, and it’s not just the architect. It is, as Apps concludes, the system. We see it every day in the shoddy construction of shabby cheap buildings that are leaky, toxic, cold and mouldy. We see it when people are unhoused and dying in the streets because ideology is placed above human lives. We see it when politicians and developers refuse to do much to reduce carbon emissions which will hurt everyone. And it’s not just the UK; it is everywhere, all the time. The only difference with Grenfell is we don’t usually have so many die in one place in such a short time.

It was good to read your post which reminded me about why the whole thing was terribly sad for so many reasons and people still don't know about all of them. I had written about it too although from a different perspective. If you are interested in cross-linking, let me know.

https://renoqueen.substack.com/p/grenfell-took-many-lives-yet-we-continue

I trained in an “armored” vehicle that used aluminum and was often criticized for sitting on the vehicle commander’s hatch ring rather than being lower in the vehicle because I knew what would happen inside the vehicle if it was hit (fortunately I was never deployed in that vehicle). Years later I learned how aluminum powder was used in rocket fuel (and in the coating on the Hindenburg zeppelin).