New study questions the ‘conventional wisdom’ that taller buildings are worse for the environment

And unless I am missing something, it confirms that the conventional wisdom is right, but also that bad design is worse than good design.

Just one more storey? The embodied greenhouse gas impacts of adding height, slab thickness, building code and design tranches is a paper written by Avery Hoffer, with Dr. Even Benz, and Dr. Shoshanna Saxe of the Department of Civil and Mineral Engineering, University of Toronto, which contradicts just about everything I have written about building height. Hoffer, seen presenting his work last year, concludes: “Don’t fear height, fear bad design.” They note in the abstract:

‘Conventional wisdom’ holds that taller buildings are worse for the environment, coinciding with longstanding skepticism of height, yet the research and data is often anecdotal or incomplete and contradictory.

Hoffer says on his concluding slide, “historical skepticism of tall buildings does not hold up when evaluated through the lens of embodied GHG emissions.” I wrote in my recent book, “When you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes.” Same lens, opposite conclusion!

Hoffer references my two favourite studies: Francesco Pomponi’s "Decoupling density from tallness in analyzing the life cycle greenhouse gas emissions of cities”, which found that high-density low-rise buildings have half the life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions of high-density high-rise buildings.

Then there is H. L. Gauch, What really matters in multi-storey building design? A simultaneous sensitivity study of embodied carbon, construction cost, and operational energy. It concludes that “The Goldilocks spot for upfront carbon is four to six stories, and for cost, six to eight. As you get higher, you pay more to add stability and bracing but less for the roof.”

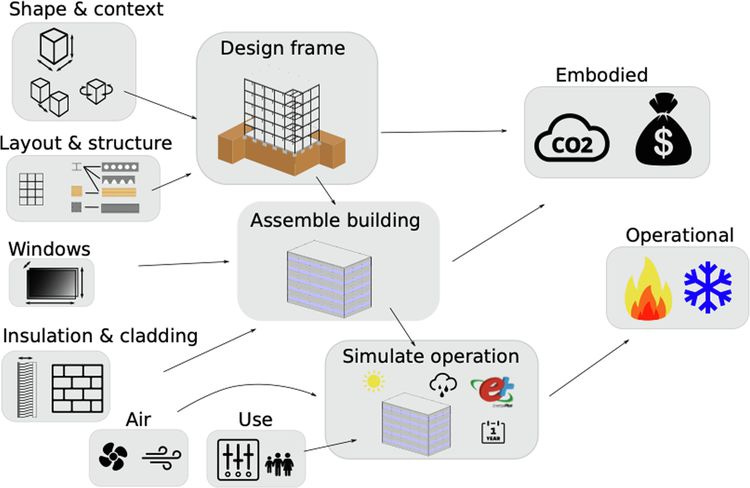

In the Hoffer et al study, 128 buildings between 5 and 20 storeys were modelled, looking at column spacing, slab thickness and height. They found that yes, as height increases, so does the upfront carbon:

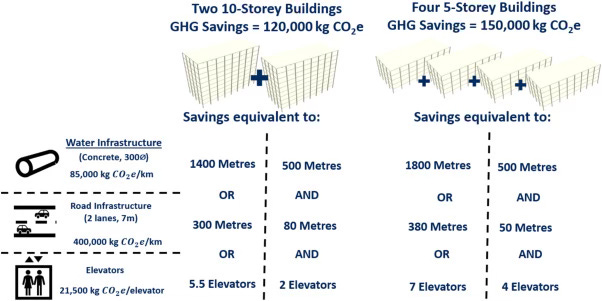

“Assuming construction with 200 mm thick floor slabs and the same total net floor area in each case, four 5-storey buildings have structural embodied GHG of 900,000 kgCO2e, two 10 storey buildings 930,000 kgCO2e and one 20-storey building 1,050,000 kgCO2e. This implies a savings of 120,000 kgCO2e if two 10-storey buildings are built instead of one 20-storey and 150,000 kgCO2e if four 5-storey buildings are built instead of one 20-storey, making it appear as though building shorter is a better option in terms of reducing embodied GHG emissions.”

On the other hand, more significant savings can be achieved by making the slabs thinner.

“In summary, increasing height by 5-storey increments increases emissions by 5%, while 25 mm increase in slab thickness increases emissions by 9% … In these increments, slab thickness is roughly twice as critical for embodied GHG than height.”

My first reaction was, “So what?” Why then don’t we design 5-storey buildings with thinner slabs and get the best of both worlds? The statement “Don’t fear height, fear bad design” makes no sense to me; bad design and over-engineering are problems at any height. As Will Arnold, formerly of the Institution of Structural Engineers, wrote in The hierarchy of net zero design, the same rules apply at any height:

“You must push to use less stuff. This involves prioritising better use of existing building stock, and then configuring new structures to minimise material use. Our massing, layout and configurations must get more efficient (we often need to convince others to enable this), and then our design methods and utilisations must deliver this with no ‘spare fat’.”

But wait, there’s more. Four 5-storey buildings need more infrastructure (water, road, and elevators) than 1 20-storey building. It’s hard to argue with that, except that we are not usually building 20-storey buildings on greenfield sites; the water and road infrastructure is already there. And we haven’t mentioned the below-grade parking needed for those 20-storey towers.

Hoffer concludes: (my emphasis)

“Height is often assumed to be the central driver of embodied GHG emissions in new buildings, especially in structural building elements – this dovetails with the long history of suspicion of taller buildings. Embodied GHG arguments are being used to oppose housing construction and cut storeys off proposed new buildings.”

Really? Embodied GHG arguments are being used to fight the demolition and replacement of perfectly good existing buildings. But are they being used to cut storeys off proposed buildings? I have never heard of that.

“We found that height-related choices (e.g. an additional few floors, taller ceilings) have smaller impacts of embodied GHG than slab thickness.”

This may well be true, but what about all the other important choices that come when you are building 5-storey buildings, such as the option of mass timber construction? Single stairs, or other tradeoffs? Just saying in the limitations section, “Other building dimensions, aspect ratios and structural systems or materials may change the embodied emission results,” misses the big opportunities. Hannes Gauch told me in an email exchange:

"Our results show that to lower both upfront and operational emissions in new multi-story buildings, we should make them compact, design with timber instead of steel or concrete, choose light cladding and modest window areas.”

In 2024, another of Dr. Saxe’s students, Keagan Rankin, published Embodied GHG of missing middle: Residential building form and strategies for more efficient housing, also talking about the design of low-rise buildings:

“On average, multi-unit missing middle buildings have significantly lower embodied GHG per bedroom than single-family and mid/high-rise buildings, but variability within forms is greater than between forms, indicating a large potential to reduce embodied GHG through building design.”

As Gauch and Rankin demonstrate, good building design is about a lot more than slab thickness and column spacing. More on Rankin’s study:

Perhaps I am missing the point, but Hoffer’s statement, “Don’t fear height, fear bad design,” is comparing apples and bicycles. His follow-up conclusion, “Results show we need to focus less on height and focus more on designing better,” is also problematic; as Rankin determined, we should focus on designing better short buildings.

The study questions the “‘Conventional wisdom’ that taller buildings are worse for the environment,” but I think the only conclusion you can draw from it is that bad design produces more upfront carbon emissions than good design. You don’t really need a study for that.

“Conventional wisdom” is an interesting phrase first used by John Kenneth Galbraith in his 1958 book “The Affluent Society.” Forty years later, he updated the book's introduction with a discussion of how the phrase is used and misused. I wrote about it in Treehugger: Why ‘The Conventional Wisdom’ on Carbon No Longer Applies

Christopher Alexander's "A Pattern Language" (1977) proposed no residential buildings over 4 stories, due mainly to psychological reasons. I believe he also preferred walkable cities.

>Embodied GHG arguments are being used to fight the demolition

>and replacement of perfectly good existing buildings. But are they

>being used to cut storeys off proposed buildings?

>I have never heard of that.

Well, it wasn't successful, but I made that argument at Toronto and East York Community Council this past summer to try to get floors removed from a development on at 1251-1311 Yonge St, south of St Clair.