Why houses should be built on stilts

Concrete and foam insulation are the biggest contributors to upfront carbon emissions in a home. Who needs them?

Over on that other social media site that I don’t look at anymore, Barnabas Calder (author of the wonderful Architecture from Prehistory to Climate Emergency, my review here) complains about “the house of the future” from 1994 that is built on stilts. He asks,

“I wonder why it has to stand on legs. Like a modernist house, given the loss of the thermal mass of the ground beneath, and the additional surface area exposed to external temperatures.”

My first thought was that anyone who has gone on a camping trip and forgot their Thermarest or foam pad (as I did on a trip to Iceland) learns pretty quickly that the thermal mass of the cold ground sucks the heat out of you far faster than the air does. You need a lot of insulation under your floor, or it’s going to be uncomfortably cold.

I pointed out that Le Corbusier built on stilts (or piloti) "to provide an actual separation between the corrupted and poisoned earth of the city and the pure fresh air and sunlight of the atmosphere above it." And Corb didn’t know about radon gas. Calder responded:

“Remember, though, that Corb's work, written, drawn and built, was an elated exploration of the ways cheap fossil fuels could change the rules of architecture.”

Yes, indeed, but when I visited Ben Adam-Smith’s wonderful Passivhaus, I learned that a common foundation in the UK involved putting concrete slabs on concrete beams, creating an inaccessible one-foot-high void that I was certain would be a grand home for all kinds of unwanted creatures. I’ll take the stilts, please; we know how to insulate now.

When I was writing for Treehugger, I often extolled the virtues of houses built on stilts. When I once described my extreme dream home, I wrote that it would be built on stilts like Juri Troy Architects’ House under Oaks in Eichgraben. It’s a prefabricated box wrapped top, sides, and bottom with two feet of wool insulation.

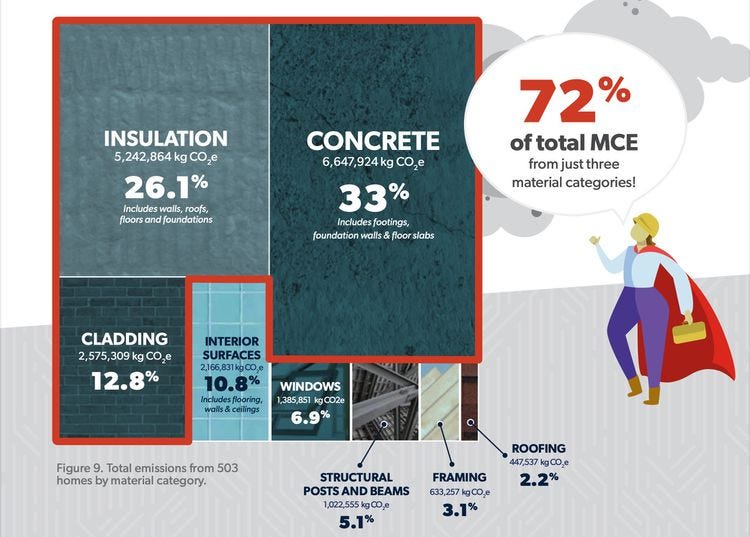

When Chris Magwood and the Builders for Climate Action (BFCA) used their BEAM calculator to examine 500 houses across Canada, they found that 60% of the material carbon emissions (MCE), a portion of upfront carbon emissions, came from concrete and insulation. Being built on stilts lets you eliminate almost all of that.

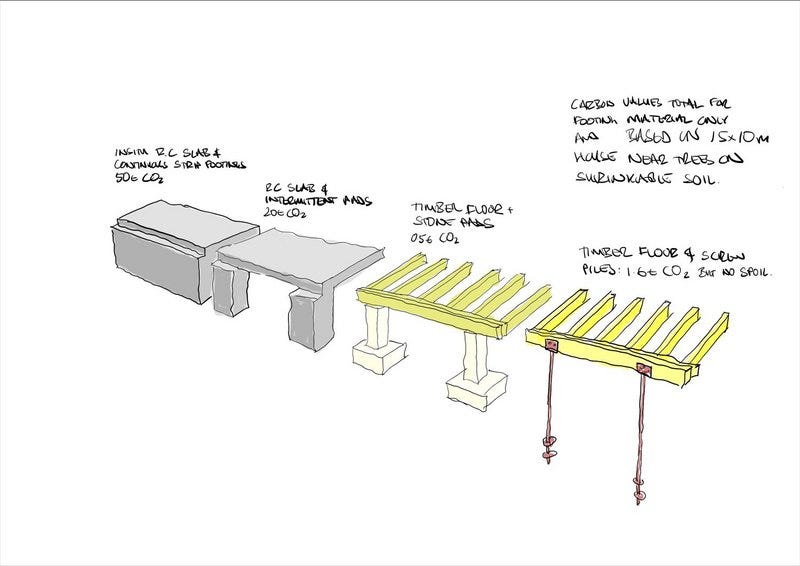

My dream house had wooden stilts sitting on helical piles, but engineer Steve Webb writes in the RIBA Journal that stone piers have even less upfront carbon emissions. He wants that first floor up in the air: “Let’s ditch the slab. It’s totally feasible to build a suspended timber floor. Not only is it lighter and quicker, but if properly detailed it will last as long as all the Victorian timber ground floors we are sat on right now.”

There are other reasons that houses might be built on stilts in the UK; this proposal from a British builder has 71 tonnes of conventional house built on hydraulic jacks so that it can be lifted up in times of flooding. Does this make any sense? Why not just design the house on stilts in the first place?

Compare that to one of my favourite houses, Kieran Timberlake’s Loblolly House, which makes a virtue of being built on stilts:

“Loblolly House also reflects an environmental ethic; by lifting it off the ground, we ensure that it touches the site very lightly. Our desire in conceiving this home was to reimagine what was possible in the realm of building—with the intention to improve the productivity of design and construction, enhance affordability and quality, and do so in an ethical and aesthetically moving manner.”

I should note that I am writing this post from my cabin in the woods north of Toronto. It is built on stilts to avoid destroying the landscape; if you want to build on conventional foundations, you have to blast the rock.

There are so many good reasons for houses to be built on stilts:

You can wrap the same low-carbon insulation right around the building, whereas conventionally, one would have to use foam in contact with the ground.

You dramatically reduce the upfront carbon emissions by eliminating the concrete and foam.

Prefabrication is finally a growing trend, and it is much easier to drop a box on piles or stilts than to connect it to a basement or crawl space.

It has a much lower environmental impact; you can just take the house away and unscrew the piles.

It’s more resilient. It is more flood-resistant, and in summer, it provides shade.

I recently visited Frank Lloyd Wright’s Affleck House in Bloomfield Hills, where he created a sitting area underneath the house with a skylight up into the living area above. It is a lovely alternative to air conditioning; those spaces under the building are not just for cars.

Bucky also got it right in 1944: Build prefab, build small, build light, and hang it from a pole. We shouldn’t be building single-family houses at all, but if we do, there are so many reasons for them to be built on stilts. That is indeed how we should build the house of the future.

I was just about to post exactly this comment. I'm 76, have experience being a wheel chair user after an accident and see friends and neighbors grappling with being trapped in houses that are reached by a couple of steps. We solved my problem with a very long modular aluminum ramp, as appoach that was adopted by several of my neighbors. Perhaps instead of a lift consideration needs to be given to either including a ramp in the design or planning for one.

Lots of good reasons for timber floors, as you’ve set out Lloyd. In NZ and Aus it is a standard way of construction to have a suspended timber floor on timber (or concrete or steel) piles. It works well for earthquakes and it’s easy enough to design for high wind uplift. Concrete slabs have been far more popular in recent decades but some are starting to go back to timber floors to reduce carbon impacts and to deal with sloping ground.