After learning how to read books again, I try to review them.

After years of reading only bite-sized content, I have a bit more time to read a bit more book.

“Bookshelf wealth” is a thing these days, described just yesterday in Dezeen as “the first major design trend of 2024.” Kelly and I are bookshelf wealthy, but it’s old money; we haven’t bought a real paper book in years. She loves the Toronto Public Library, and I am not very good at reading books.

For years, when I had to feed the beast that was two posts a day at Treehugger, I read magazines, newspapers, blogs and social media in my search for stories. I loved short bits and lived in Twitter. I rarely made it through a Youtube videos, let alone a full hour of TV. Podcasts are impossible if I am not trapped in the car. You could say I had a short attention span.

Everything changed when I got laid off from Treehugger; I had time on my hands, and decided I had better learn how to read a book again or I would drown in social media. I still don’t do fiction much, and have pretty much stuck to books that are relevant to my work here and to my teaching, but I am broadening my interests. Here are some of the books that have mattered to me this year- short on criticism and long on quotes, because I am not very good at this either.

Blood in the Machine/ Brian Merchant

I wrote about this book in my post Writers: Stop it with the AI images already. You're next. I was inspired by Brian Merchant’s book, and by the Luddites who did not object to technology, but to exploitation, to being put out of work by machines that did a crappy job but could be operated by children and could turn out massive quantities of cheap goods fast and make the owners extremely rich. It changed many of my views of technological “progress” which always seems to be more of the same: how to drive down labour costs with machines that replace people or make them accept lower pay. So I won’t use AI and am going to stop using the self-checkout, and will no longer go to stores like Canada’s Shoppers Drug Mart where they force you to the machines because there is only one checkout line with a human. Brian has radicalized me with his words:

The time is again ripe for targeting the “machinery hurtful to commonality”—the gig app platforms, the fulfillment-center surveillance, the delivery robots, the AI services, the list goes on—duly singled out by those whose livelihoods are being migrated, against their will, by this generation’s tech titans, onto unforgiving technologized platforms, or degraded and whittled away by automated systems.

Architecture from Prehistory to Climate Emergency/ Barnabas Calder

In the introduction, Barnabas Calder claims that “This book is the first to ask how humanity’s access to energy has shaped the world’s buildings through history.” I thought, this could not possibly be true, I have read dozens of them. But most of these books concentrate on the “operating energy”- how people kept warm or cool once they were occupying the building. Calder views the bigger picture, looking at:

….the great effort invested in constructing a large building – what contemporary architects refer to as ‘embodied energy’ – was expensive and difficult to obtain. Buildings were built only when the need was pressing or the sponsors powerful. Once up, most buildings were designed to demand as little ongoing energy as possible – domestic open fires were much the biggest ongoing energy cost of architecture, providing warmth, but also cooking heat and light after sunset. With the rise of fossil fuels, the initial financial cost of materials and construction dropped sharply, even as the energy consumption of these processes rose.

Calder is the first to look critically and in detail at the energy consumed making the materials and constructing the buildings, something we have only recently become concerned with. I have written often that “When you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes.” Calder looks back through the embodied energy lens, and it changes one’s view of architectural history.

I am not sure he is always right; we learn that the Romans had lots of cheap labour and built out of stone, since making lime and firing bricks was expensive and used tonnes of wood for fuel. But when I visited the Colosseum, it appeared to be built of concrete poured into brick formwork, with all the stone cladding that used to cover it stolen for other buildings. But it is a minor cavil, given the scope of the book.

The development of fossil fuels led to the end of what was called “‘the photosynthetic constraint’: any society that is dependent on new-grown plant matter for almost all its energy is constantly having to balance the areas of firewood and food crops on its finite land, with more of one meaning less of the other.” We quickly learned how to make iron and steel, cook sand into glass, and reduce limestone to calcium oxide and make cement. All of these processes release vast amounts of carbon dioxide, leading to the problems we have today, problems hardly anyone is willing to deal with. As Calder notes in his concluding chapter,

Unless a new project can either be proved to offer a carbon saving within a fairly short timescale or be shown to be overwhelmingly necessary, the presumption should be that the existing building is kept and upgraded. For now, though, the case for doing less is argued for by few and easily shouted down by well-funded marketing departments selling a succession of financially profitable interventions whose noisy claims of improving environmental performance are unproven.

But he doesn’t fall for the long lifecycle card used by the concrete and steel people, getting the difference between now and later emissions, the time-value of carbon.

If carbon savings are only to be realized over the course of decades then many of the buildings for which this argument is made may have been washed away by the rising seas before they have time to recover their initial carbon investment.

I have read many histories of architecture over the decades since architecture school, but Barnabas Calder uses a different lens, and everything changes.

Material World/ Ed Conway

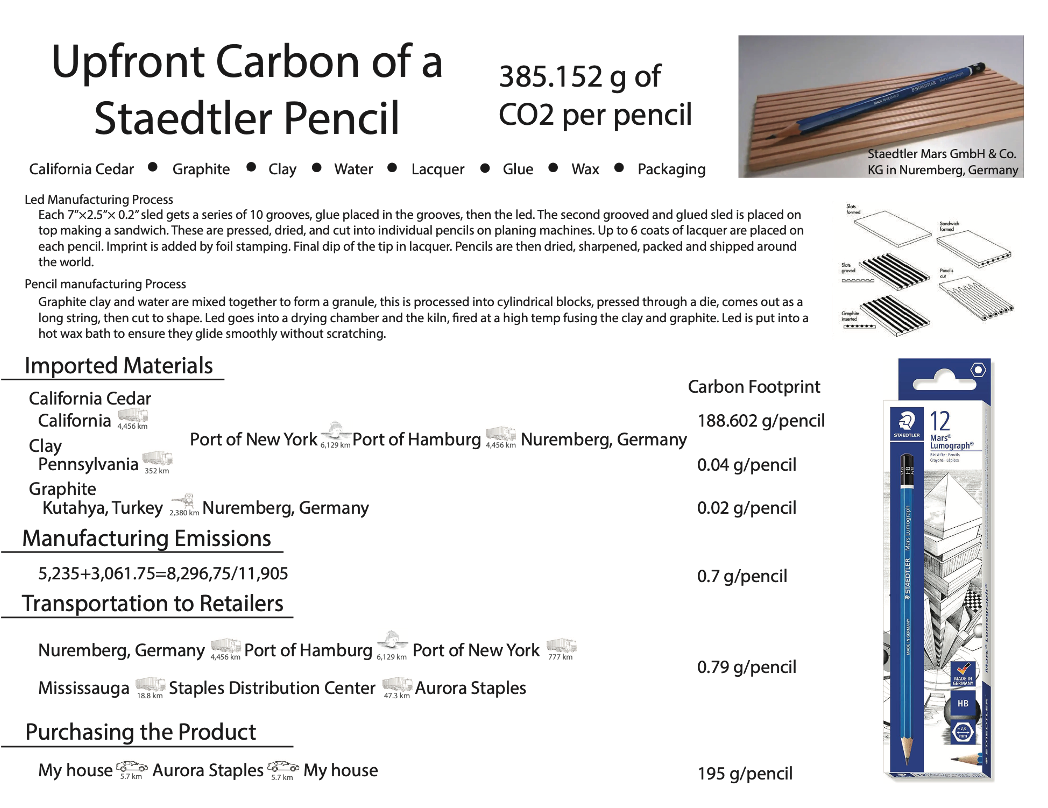

The assignment for my Sustainable Design Students at Toronto Metropolitan University was to pick an object, figure out what it was made of, and calculate the corbon footprint of each of the components. One of them chose a pencil, and it was remarkable;

The wood came from California, clay from Pennsylvania, the graphite from Turkey, all shipped to Nuremberg for assembly and then shipped back to Aurora, Ontario, where she bought it.

Conway’s book mentions the wonderful 1958 essay by Leonard Read, I, Pencil, as one of the inspirations for this book. He asks, “Surely if we spent a little more time contemplating how the items upon which we rely actually get produced, we might not be so baffled when they run short. Thanks to Read’s essay, millions of economics students now know their way around the supply chain of a pencil, but what about a smartphone or a vaccine or a battery? What about the supply chain for carbon dioxide or borosilicate glass?” Conway looks at salt, iron, copper, oil, lithium and sand, noting:

“This grain of silicon will have circumnavigated the world numerous times. It will have been heated to more than 1,000°C and then cooled, not once or twice but three times. It will have been transformed from an amorphous mass into one of the purest crystalline structures in the universe. It will have been zapped with lasers powered by a form of light that you can’t see and doesn’t survive exposure to the atmosphere. This—the process of turning silicon into a tiny silicon chip—was the most extraordinary journey I had ever traced.”

I was a bit embarrassed reading this book, having just written my latest while sitting in my chair at a computer. Conway goes to the bottom of mines, to the inside of foundries, to the brine ponds in Bolivia. It’s a fun tour.

The Lost Supper/ Taras Grescoe

Like most urbanists, I discovered Taras Grescoe via his 2012 book “Straphanger.” Then I bought a set including Bottom Feeder, “a seafood lover’s round-the-world quest for a truly decent meal” and The Devil’s Picnic, a wonderful tour of foods that can kill you. I am no cook and do not read many books about food, but I eat up everything Grescoe writes. A small example about cheese:

Cheese is, after all, a miracle. From only three ingredients, an almost infinitely variegated range of flavors and odors can be manifested in solid and delicious form. Depending on how you manipulate them, salt, rennet, and the milk of a ruminant mammal can metamorphose into a dainty pyramid of spreadable young Valençay goat cheese, or a massive eighty-three-pound wheel of hard, savory Parmigiano-Reggiano. Like the finest of wines, a well-made cheese is a poem, in which formal constraints create the conditions for aesthetic transcendence.

He teaches us to be time travellers.

I HADN’T EXPECTED THIS JOURNEY to take me quite so far. A wild impulse to experience the taste of ancient foods had brought me to spots on the globe I’d never imagined going: a windswept barrier island off the coast of Georgia; the aquatic gardens of Mexico City; the flanks of a volcano in the heart of Turkey. And though I’ve been to more distant places in my life, I’ve never traveled further back in time. As big as the world is, the past is even bigger, and the beautiful thing is that you don’t have to go far to find it: it’s all around us, in the soil under our feet, in the canopies of the trees overhead, in the food in our kitchens, and in our memories. The secret to time travel, it turns out, is that humans today are identical in physique, intelligence, and problem-solving abilities to just about anybody who has lived in the last sixty thousand years. When confronted with a problem—like how to build a shelter or assemble a meal—our prehistoric ancestors drew on the same set of innate capacities that we possess. The challenge, I realized, was seeing the world through their eyes. Once I knew that, the only things I needed to travel in the past were my own curiosity and imagination.

Beautiful writing, and it is just so much fun following in his footsteps. And I am never eating butter again.

The Unknown Shore/ Patrick O’Brian

David Grann’s The Wager was one of the most popular books of 2023, #1 on the New York Times Bestseller list for weeks. Patrick O’Brian’s sea stories about Jack Aubrey and Doctor Maturin are also hugely popular; I have read every one of them.

I had not read The Unknown Shore, one of O’Brian’s first books, written in 1959 before any of the Aubrey/Maturin novels. It’s actually a novelization of the story of the Wager, with the captain and the doctor being the main focus of the book, and the models for Aubrey and Maturin. This is definitely not up to the standard of the later O’Brian sea stories, but it was fascinating to see how the story of the Wager was the start of such a famous series of books.

What have you read that you loved, and you think we should read? Leave a note in comments.

Nonfiction: I just finished The Identity Trap (Yascha Mounk) and Doppelganger (Naomi Klein) and found them immensely worthwhile. Older: Fantasyland (Kurt Andersen, 2017) rang true (and scathing).

Climate/design nonfiction: I found Flourish (Sarah Ichioka, Michael Pawlyn) to be compelling (in part because I have a big crush on Doughnut Economics, which figures in here, as well as an unbridled optimism about potential of remapping things toward regeneration).

Fiction: on the climate fiction front, The Deluge (Stephen Markley) was quite an engaging long romp, if you have the stomach for it, and I enjoyed The Ministry for the Future (Kim Stanley Robinson).

I’d also recommend The Dawn of Everything by Graeber and Wengrow. Similar to Calder in that it reformulates human history.