What happens when we get a clean slate? We write the same thing again

A depressing visit to the Marshall Fire reconstruction shows we have learned nothing.

Spring was unusually damp in Colorado in 2021, and the grass grew high. Summer and fall were unusually dry, and by then, so was the grass. The winds on December 30th were unusually strong; Andrew Michler says houses were shaking. Brad Begin of Alpen Windows described the start of the Marshall Fire at the recent Passive House Network Conference, noting that he kept calling the fire department and was told more than once not to worry; it’s just a grass fire and is under control. And then it wasn’t; less than 12 hours later, over a thousand houses were destroyed.

One might think that this would be an opportunity to build back better, given that unusual weather conditions are a sign of the times, and that was the plan in the municipalities of Louisville and Superior, which had cranked up their building codes. But many residents didn’t want that, complaining that they didn’t have the money. The insurance companies didn’t want that, noting that the houses that burned were built to the 1990 codes, and that was all they were going to pay for. So Louisville waived its Net Zero requirements, and Superior rolled back to the 2018 codes, which are less restrictive than the 2021 requirements.

While some chose to build more efficient houses, just a few were built to the Passive House standard. And there was no discussion at all about planning- it is all single-family detached housing.

To be fair, people needed houses in a hurry. The insurance companies insisted that the houses be finished by the end of this year, so it is not surprising that so many houses look like they are right out of an online plan site. But the problem is that between the houses and the planning, they have locked in energy consumption for another couple of generations, or at least until the next fire.

On a house tour organized by the Passive House Network, we visited two subdivisions torched in the fire: one with many big lots and three-car garages, and one that designer Andrew Michler described as “working class” with million-dollar houses that had only double garages.

Generally, it appears that people may not be able to afford insulation, but they have enough for gables on gables on gables, plus a few box bays.

Nobody thinks about how every one of these boxes and bays and jogs costs more money, creates thermal bridges that lose more energy, and sets up opportunities for leaks. They seem just to want complexity and more gables than their neighbour.

Even though there is lots of sun and people are installing solar panels, nobody seems to think about how the useless gable is going to compromise the solar installation, because nobody seems to talk to anyone else.

Architect Bronwyn Barry has a game that she calls “Spot the Passive House,” where she posts a Google view, and you look for a house with a simple form and no gables or complications in the roof. they are usually what Bronwyn hashtags as #BBB: “Boxy But Beautiful.” You can do it as you drive by, too; they are recognizably different than their neighbours, like this Passive House made of B.Public prefab panels.

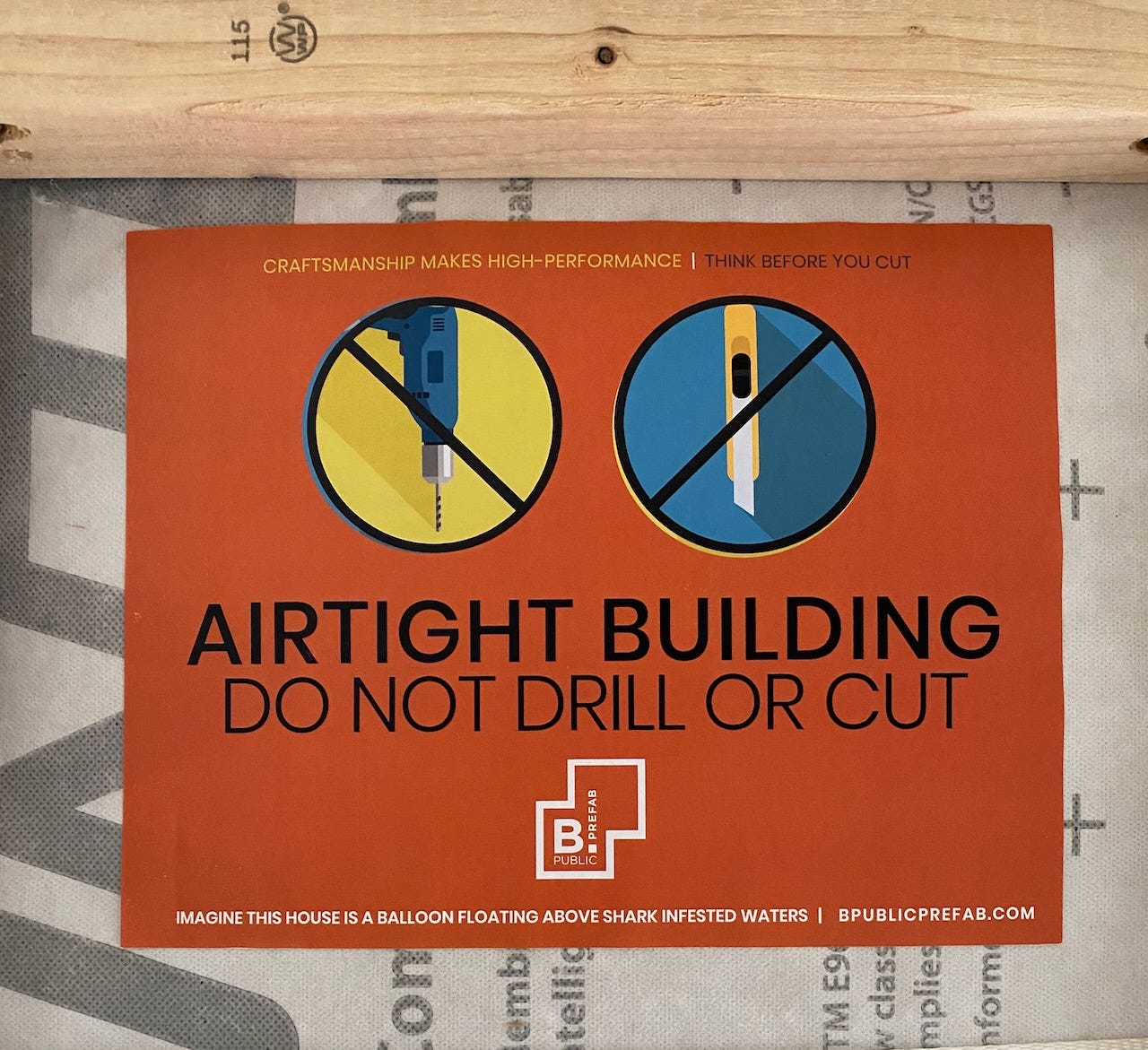

What matters in a Passive House is not the number of gables but the number of holes. You generally keep it simple and build with care because “craftsmanship makes high performance.”

The simpler, boxier forms are one identifier; another is the separation of the garage from the house since it is outside the Passive House envelope and has a lot of surface area. Shape Architecture has done a good job of integrating this house into the sloping site; the main living spaces start one floor up, and the roof of the garage will be heavily landscaped.

It is instructive to compare it to the house right next door. Here, a standard plan has been modified for the slope by jacking it up a flight of stairs and dropping the garage so far that you could probably get an entire room in above it behind that massive white panel of siding. Oh, and they want a third garage, so let’s just tack it on the side.

The Restore Passive House by Andrew Michler and Rob Harrison pops as Passive House with its simple forms and the garage outside the envelope. It loses on its gable and doodad count but wins everywhere else. It was designed to be replicated; although the plan is an L-shape instead of a more efficient box, Rob Harrison told me earlier that “it creates four roof planes facing in different directions, so they can site the house on any lot with any orientation, and still have lots of roof facing south for solar panels.” Note also the lack of roof overhang, so that fire or wind can’t get under the eaves, and then look at all the other “fire resistant” houses.

There were many things to love about this house, including its modesty and simplicity and what’s that- a kitchen with walls! A dining room at the front, a living room at the back, and a kitchen in the middle! Of all the houses, big and small, this is the only one where you can eat your dinner without looking at dirty pots and pans. I continue to believe that this makes more sense than an open plan.

More on why it’s time to return to the closed, separate kitchen.

Like the previous Shape Architecture house, looking at the neighbours is instructive. On one side is a Boxy but definitely not Beautiful (those windows!) house built of ColoradoEARTH compressed earth blocks. “CEBs have an impressive low carbon footprint due to the fact they are made with local materials that are considered overburden to the quarry. The blocks are unfired, easy to construct, and energy-efficient.” Inside the garage were bags and bags of Earthaus stone plaster and lime stucco finishes- this is going to be one very healthy green house.

There are good reasons to design what have been called dumb boxes, and I have written: “If we are going to ever get a handle on our CO2, we are going to see a lot more buildings without big windows, without bumps and jogs. Perhaps we might even have to reassess our standards of beauty.” I wrote in my last post, Why we need windows with purpose, that they should be small and designed from the inside out according to the need for light and view, and not for aesthetics. I might have to rethink that.

On the other side, a reminder of why we are here: the charred foundation, all that is left of a house that burned. I thought concrete was fireproof, but even it couldn’t stand the heat.

In the end, I could only shake my head at the billions of dollars that have been spent rebuilding Sprawlville; one could have housed ten families on this site. Instead, we are housing cars. When they talk about what caused the Marshall Fire, you hear about how it was either a power line or a cult, not the unusual spring and fall weather or the incredible windstorm. Natasha Stavros of the University of Colorado told Scientific American: “It’s the first time in my career I have felt comfortable saying this is a climate fire,” caused in part by emissions from pouring concrete and driving giant pickup trucks. So what do we do? We just build more of the same, with concrete HardiePlank siding this time. Because, in the end, we have learned nothing.

Good article thanks. One question- are eaves not a good and useful thing? The old villas here in NZ were built with eaves to shade windows from the sun (occasionally oriented incorrectly to a Northern aspect due to confused Northern hemisphere immigrants). We did the same thing with our (otherwise relatively simple and boxy 2 storey) home to help shade the north and west facing windows. It's not perfect, but it does make a difference.

Good article, glad someone is saying this, but not enough people are listening. Colorado is an example of things that are wrong with house building. It's grotesque in many areas. With the natural sunlight, it's possible to get a lot of passive heating, and don't forget solar thermal panels--you can heat water and run the hot water thru the floors or into radiators--thus getting the sun's energy cheaply and without needing PV wiring.