Kitchen bloat is everywhere, from tiny homes to monster homes

It's time to return to the closed, separate kitchen, and to lose the giant gas stoves.

Over on Treehugger, my former colleague Kim shows The Nest, a 545-square-foot cabin available for short-term rentals. The kitchen dominates the scene with a full-size range and oven, dishwasher, and a giant double-door fridge. Kim writes that the “dining table is compact but enough for two people to eat their meals. The round shape facilitates the circulation to flow more readily around it and is a great trick to make small spaces feel less cramped.”

It’s bizarre. A short-term rental with enough fridge and cooking space to feed a dozen people and a table for two. You are essentially living in the kitchen.

I have seen this repeatedly in tiny houses, where everything is squished except the kitchen. This one, seen at Greenbuild in Atlanta a few years ago, had a full-size gas range with recirculating hood and a full-size fridge, both sticking out into the space, and hardly any room for anything else.

Our cabin, where I am writing this from, is designed around the dining room table, a 40” by 8’ slab of old bowling alley. It’s all about feeding the family and friends and seats ten people. We play ping pong on it. The kitchen, down at the end, has a small fridge, a double sink, and a range top; there is no oven or dishwasher. The size of the table has priority over the size of the fridge, and we manage just fine.

After speaking at a Passive House conference a few years ago in Portugal, I stayed at an AirBnB in Porto, designed and owned by an architect named Claudia. She chose a two-element induction range to allow for more counter space and everything else hidden away. How much more do you need, especially for a short-term rental?

All opened up, there is a lot of kitchen! It seems much more sensible, especially if you are in a small space, to hide it away like this; nobody wants to look at this stuff all the time.

And it turns out that nobody wants to look at toasters and coffee makers at the other end of the scale, in the monster homes, either.

A recent article in Insider looked at the trend of having a full second kitchen where the actual day-to-day cooking is done, with the big fancy kitchen just for show. Kitchen bloat has gone beyond giant islands to having multiple kitchens. They are like bacteria going through binary fission, where they grow to twice their size and then split in two.

“One will serve as the main kitchen that you see when you walk into a home, while the secondary kitchen is more closed off. The second space functions somewhat like a butler's pantry, which is typically a walk-in pantry with counter space for food prep or a sink. However, a second kitchen is truly just another room in your house and will have appliances, like a dishwasher, refrigerator, or even a stove, in addition to cabinetry.”

I have been railing about this since I first saw it described as a “messy kitchen” in a seniors housing project in Florida where there were actually three kitchens: the show kitchen, the messy kitchen, and the “summer kitchen.” I wrote:

“This is insane. There is a six-burner range and a double oven in the kitchen and another big range and exhaust hood in the outdoor kitchen — but they know full well that everyone is hiding in the messy kitchen, nuking their dinner, pumping their Kuerig and toasting their Eggos.”

What I hope is happening now is the return of the closed, separate kitchen, which we never should have given up on in the first place. Kate Wagner, an architectural critic who studied acoustics, dislikes fancy open kitchens. She wrote in Citylab that technological changes made the open kitchen possible:

“When inventions such as central air conditioning and improved fire suppression became commonplace, the kitchen, no longer a place of shame and no longer reliant upon the ventilation provided by the kitchen door, began to shift to different parts of the home.”

Wagner thought the open kitchen was an acoustic nightmare. “Nothing is more maddening than trying to read or watch television in the tall-ceilinged living room with someone banging pots and pans or using the food processor 10 feet away in the open kitchen.”

I think it is also a thermal and health nightmare, with particulate pollution and grease spreading throughout the home. I often show this Wolf appliance ad, with a giant gas range on an island, a flat-bottomed extractor fan (you can’t call that a hood!) that is too small and too far away to do anything. Do any serious cooking in this kitchen and the piano will be be too greasy to play. As engineer Robert Bean noted,

“Since there are no environmental protection regulations governing indoor residential kitchens, your lungs, skin and digestive systems have become the de facto filter for a soufflé of carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, formaldehydes, volatile organic compounds, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, fine and ultra fine particles and other pollutants associated with meal preparation. Toss in the exposed interior design features and what is left behind is an accumulation of contaminants in the form of chemical films, soot and odours on surfaces, similar in affect to what one finds in the homes of smokers.”

Now go back to that tiny home with the giant gas range and the recirculating fan in the combo microwave unit and imagine what the air quality is going to be like in there.

However, I disagree with Kate Wagner about how we got open kitchens; it wasn’t technology; it was society. According to Paul Overy, the thinking after the First World War was that women shouldn’t be trapped in the kitchen but should get in and get out as fast as they could, which is how we got Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky's Frankfurt Kitchen. Overy writes:

“Rather than the social centre of the house as it had been in the past, this was designed as a functional space where certain actions vital to the health and wellbeing of the household were performed as quickly and efficiently as possible… to prepare meals and wash up, after which the housewife would be free to return to her own social, occupational or leisure pursuits."

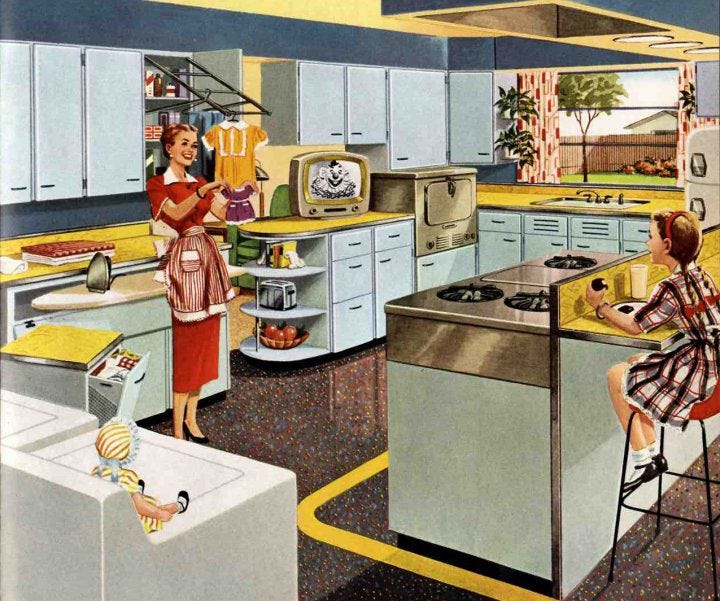

That all changed after the Second World War when women left the factories and offices and returned home to birth the baby boomers. The kitchen was designed to be, once again, the social centre of the house. Forget her own social, occupational, or leisure pursuits; there are kids to raise and husbands to feed! The open kitchen would give women space and freedom from being trapped in a small room. But did it?

Whenever I complained about open kitchens, people would send me this drawing, saying, "You see!" they write. "Everybody wants to live in the kitchen!" or "Open kitchens all the way. The kitchen should be the heart of the house, not tucked away out of sight and mind."

I tracked down the source, a study called "Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century,"and found it said the opposite; few people were happy with them.

“Parents’ comments on these spaces reflect a tension between culturally situated notions of the tidy home and the demands of daily life. The photographs reflect sinks at various points of the typical weekday, but for most families, the tasks of washing, drying, and putting away dishes are never done. ... Empty sinks are rare, as are spotless and immaculately organized kitchens. All of this, of course, is a source of anxiety. Images of the tidy home are intricately linked to notions of middle-class success as well as family happiness, and unwashed dishes in and around the sink are not congruent with these images.”

The study also noted that the counters were often “fully laden with piles of bills, bulky toys, and the ephemera of daily living.”

In the end, I believe that the trend toward messy kitchens proves that Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky was right all along in designing a small kitchen that was a machine for cooking. Nobody needs an island big enough to land an airplane on. Nobody wants to look at dirty dishes. Nobody wants to breathe particulates and nitrogen oxides. Nobody wants toddlers and dogs underfoot. And nobody needs two kitchens, what the New York Times described as a “social kitchen” plus a “chef’s kitchen.” One is enough, but make it messy and separate.

And, of course, there should not be a gas range in any kitchen.

Our house is a little less than 1700 square feet of living space. Around 1000 square feet covers our open plan kitchen, living, dining space. Because that space is open and the house is very airtight and well insulated, we heat it with a single minisplit heat pump. If the space was three separate rooms, we'd need a different, more expensive, less efficient heating system, either a ducted heat pump with ducts running to each room or a multisplit heat pump with heads in each room.

Open plans aren't for everyone, but they work well for us and for a lot of people. We like having the winter sun penetrate into the kitchen on the North side. It's a fairly modest kitchen that I built myself.

As for huge kitchens with $15,000 ranges, I suspect there's an inverse relationship between them and actual nightly meal preparation.

Lloyd wrote: "What I hope is happening now is the return of the closed, separate kitchen, which we never should have given up on in the first place."

Hope springs eternal, as they say—but it flies in the face of social convention, as well as interpersonal and familial norms. The kitchen has been, and always will be, the heart of the house (or is it more apropos to write it's the stomach of the house?)

Either way, there's a lot to unpack from the quote that somehow "proves" it is the complete opposite: “Parents’ comments on these spaces reflect a tension between culturally situated notions of the tidy home and the demands of daily life. The photographs reflect sinks at various points of the typical weekday, but for most families, the tasks of washing, drying, and putting away dishes are never done. … Empty sinks are rare, as are spotless and immaculately organized kitchens. All of this, of course, is a source of anxiety."

Anxiety? Really? Is that how our ancestors looked at it instead of a prep-do-finish task performed multiple times a day? How far we've fallen! Here's what you need to know:

A. Teach your children responsibility. When the meal is done, clear the table, load the dishwasher.

B. Learn to do a task to completion. Meals do not end once the food is off the plate.

C. Learn how to declutter your life. If dishes pile up, DO THEM AS SOON AS THE MEAL IS DONE. If the counters are “fully laden with piles of bills, bulky toys, and the ephemera of daily living” then learn how to tackle those things AS THEY COME IN. Everything has a place; if kids throw their books on the floor, teach them how to put them away in their rooms. If the table is where all the bills land, BUY A FILING CABINET AND/OR INBOX/OUTBOX TRAYS. If toys are on the counters, either make the kids put them back where they belong or throw them out. The crying fit of losing a beloved toy only needs to be endured once before it never happens again. In other words, BE A RESPONSIBLE PERSON. If you're a parent of young kids, BE A RESPONSIBLE PARENT AS WELL. "Parent" is not just a noun, it's a verb.

No one wants unexpected guests—let alone someone invited to a planned dinner—to walk in and see a messy house, no matter how well-loved that house is. It's decorum, it's civil, it's good manners. Yes, it stems from the 1950's housewife who could often expect unexpected guests to stop by because many of her neighbors' wives also were stay-at-home moms and people typically didn't lock their front doors. But the idea that we should preferentially embrace clutter and sinks or counters full of dirty dishes as being "normal" or superior to a clean, clutter-free kitchen is wildly ironic given your aesthetic for minimalism and modernism, Lloyd.