The new manual: What is the purpose of a window?

Do we need them at all? If so, how many and how big?

Last April, I proposed a series of weekly posts called The New Manual of the Dwelling, a play on Le Corbusier’s Manual of the Dwelling published in 1927. I then produced exactly one post and got distracted, as is my wont. However, my post last week about kitchen islands was very much in this vein, so I am picking it up again, looking at parts of a home or building, starting with windows.

A recent blueskying by Jeremy raised the question of whether we need windows at all, particularly in bedrooms. It’s a good question in this modern world when you consider the traditional functions of a window, which are numerous. I looked at how they used to work in a Treehugger post.

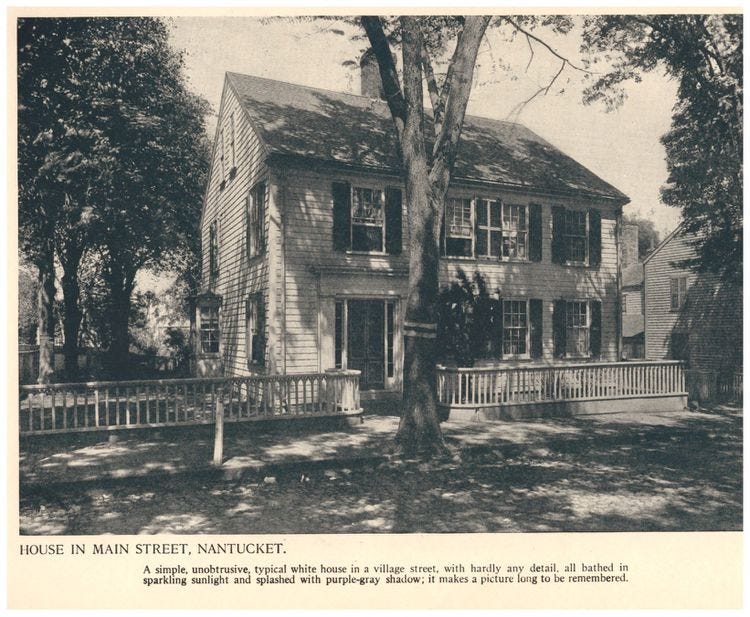

“In 1810 glass was really expensive, so even though there was not much artificial light, they made windows as small as they could and still get enough light to see. They were double-hung so that you could tune them for maximum ventilation. They had shutters for security and privacy while maintaining ventilation, and interior sheer blinds to cut glare. There is an overhanging cornice to keep the rain off so that they would last longer. There would be at least two in every room for cross-ventilation, and heavy drapes in for keeping the heat in during winter. This was a hard-working, carefully thought-out piece of climate control. There is not a motor to be seen and 200 years later, it still works.”

But this isn’t the case anymore. We have better technology.

Light:

Windows are like solar panels, useless at night! We have LEDs now that can do the job 24-7. Some say that light from windows is free, but it’s not; you have heat loss and heat gain and the expensive window to pay for. LEDs are so efficient that they might well be cheaper.

Ventilation:

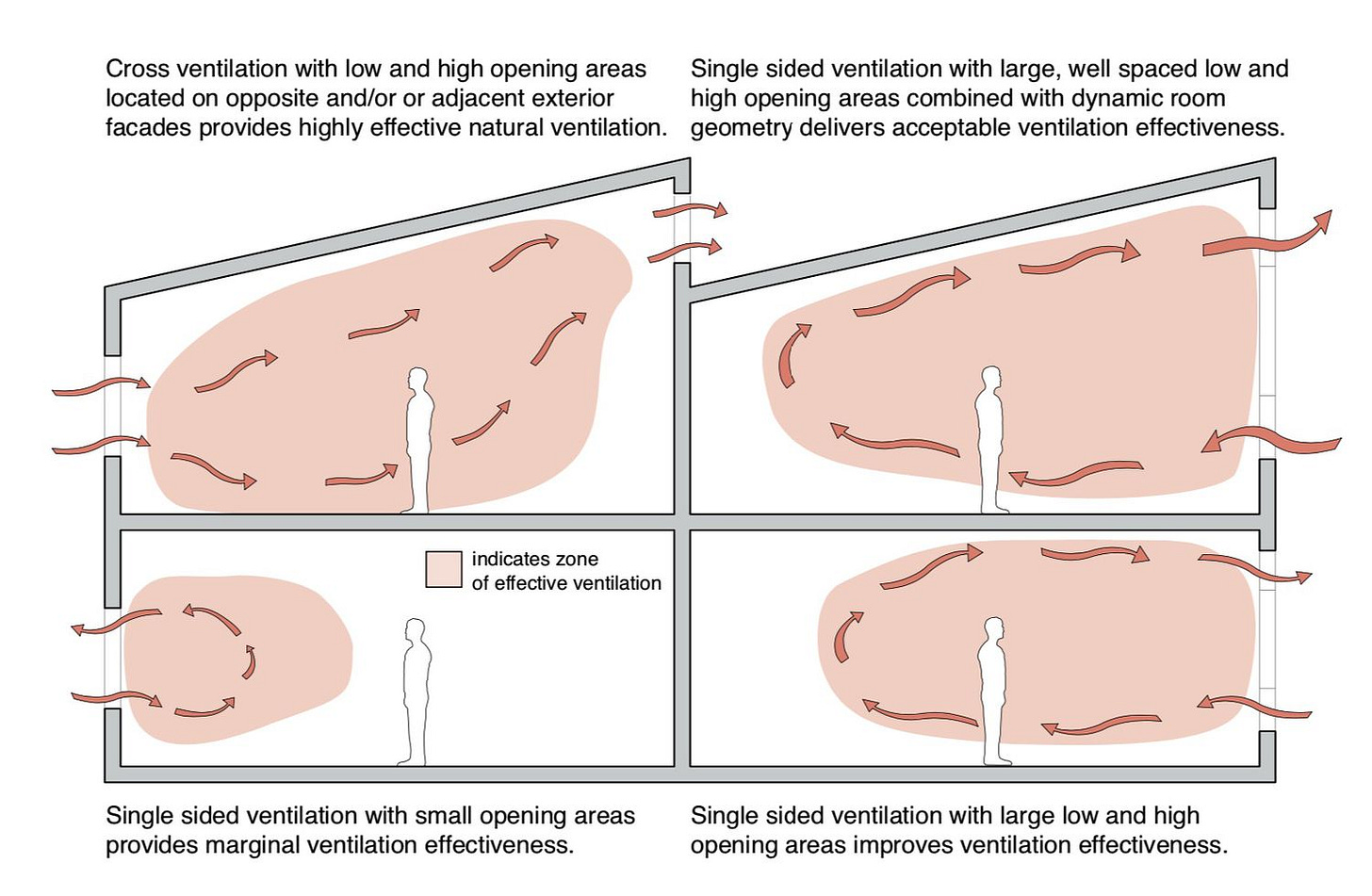

It only occurs when the window is open, which in many parts of the world is only part of the year. The outside air now is often dirtier than the inside. Architects and designers forgot how to design for natural ventilation years ago; even when they provide opening windows, there is no cross-ventilation, and they are almost useless, like Ted Kesik’s image on the lower left. We might well be better off with good quality mechanical ventilation with heat recovery ventilators and MERV 13 filters.

Heat:

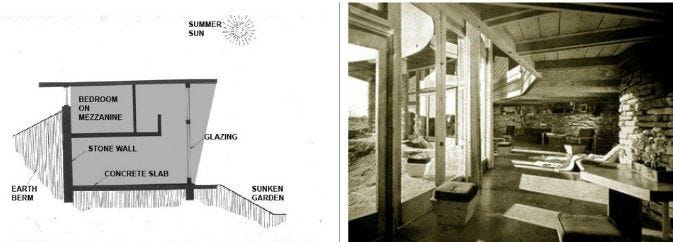

For decades, from Frank Lloyd Wright through the Passive Solar designers in the 70s, designers tried to use large south-facing windows and a “mass-and-glass” approach to heat their homes with the sun. It often didn't work; When Frank Lloyd Wright did it in the Jacobs Hemicycle House, he didn't have double glazing, and the house would lose all its heat at night, even after the owners installed heavy curtains. In "The Solar House," Tony Denzer writes that the family would all get dressed in the bathroom, the only room with a radiator. A 2010 study covered by Martin Holladay of Green Building Advisor found that “south-facing windows are so expensive that the value of the heat gathered by the windows is too low to justify the cost of the windows.” Holladay concludes: “Every extra square foot of glazing beyond what is needed “to meet the functional and aesthetic needs of the building” is money down the drain.”

Aesthetics:

The problem with Holladay’s conclusion is that few tools in the architect’s aesthetic toolbox are more important than windows, and aesthetics are now driving this bus. Bigger windows often make better-looking buildings, and architects are often lost when they have to make them smaller. When the Province of Ontario put limits on the wall-to-window ratio, the architects couldn’t cope and started adding decorative elements, jogs, and bumps that probably ate up much of the energy savings from smaller windows. They can’t cope in Munich, either, with the ugliest building I have ever seen.

Professors Jo Richardson and David Coley make the case:

“If an architect starts by drawing a large window, then the energy loss from it might well be so great that any amount of insulation elsewhere can’t offset it. Architects don’t often welcome this intrusion of physics into the world of art.”

What is the purpose of a window?

The title of this post is a riff on a lecture Monte Paulsen of the Climate Ready Buildings Group gave in Denver at the Passive House Network Conference, covered earlier here. Monte noted:

“Over-glazing brings high heat loss, overheating, storm damage, and costs more. Only place a window where it has a specific purpose and where it is the best solution to serve that purpose. Common purposes: light, view, ventilation.”

Engineer Nick Grant says much the same thing: windows can cause “overheating in summer, heat loss in winter, reduced privacy, less space for storage and furniture, and more glass to clean.”

Given that I have already dispensed with light and ventilation, I suggest that in the end, it mostly comes down to view, to our connection with the outside. But this is critically important for several reasons:

Circadian Rhythms

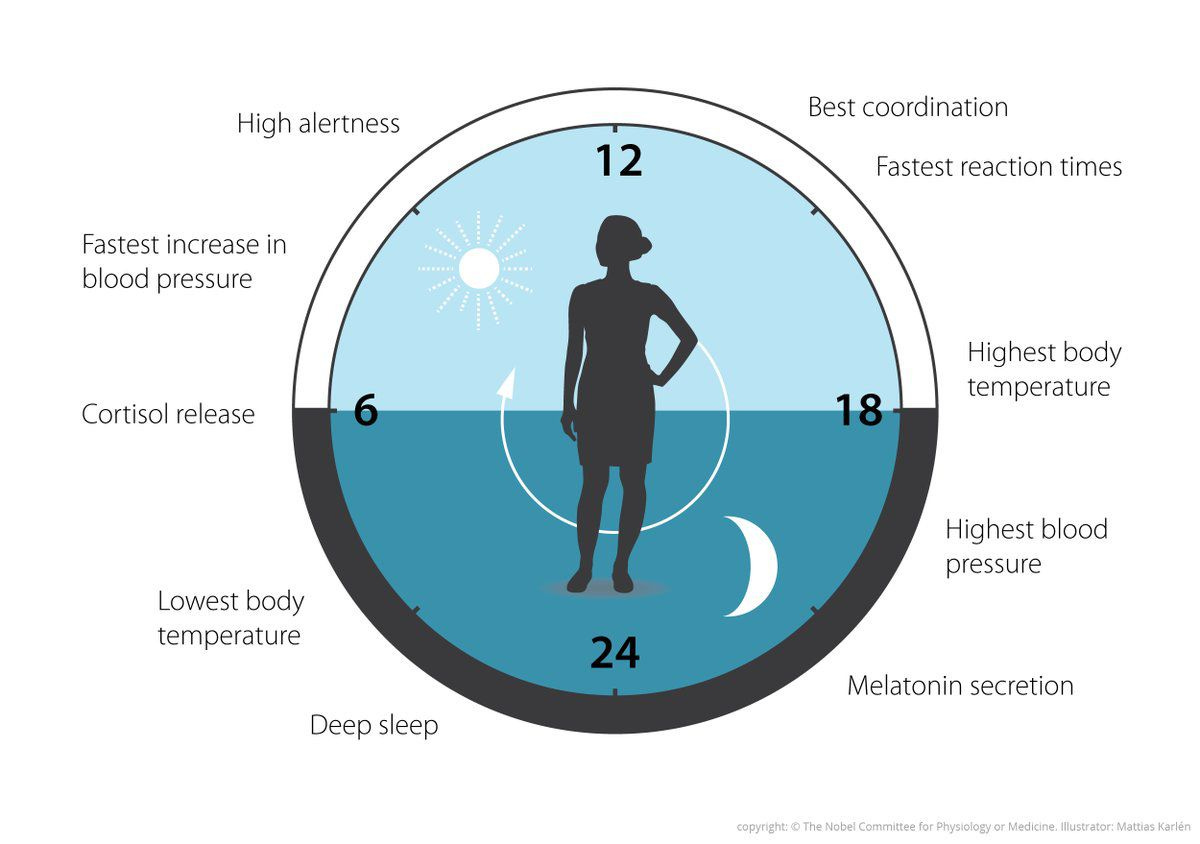

We are seeing more and more windowless apartments and hotel rooms. There is no right to natural light for workers, who can spend eight hours a day or more in windowless offices or factories and get no exposure to natural light. Helen Sanders and Pekka Hakkarainen wrote in 2014:

Over recent years, a large amount of data has accumulated demonstrating the harmful effects on human health due to lack of daylight and exterior views. The human body’s circadian rhythms not only manage sleep-wake cycles, but also many other important biological functions of the body such as hormone production, weight management, and immune systems. The production and suppression of melatonin is key to the regulation of these functions, and this is triggered by the light-dark cycles of daylight.

This was confirmed in 2017 with the Nobel Prize for Medicine, given to Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young for figuring out circadian rhythms. From the Nobel announcement:

“The biological clock is involved in many aspects of our complex physiology. We now know that all multicellular organisms, including humans, utilize a similar mechanism to control circadian rhythms. A large proportion of our genes are regulated by the biological clock and, consequently, a carefully calibrated circadian rhythm adapts our physiology to the different phases of the day. Since the seminal discoveries by the three laureates, circadian biology has developed into a vast and highly dynamic research field, with implications for our health and wellbeing.”

As Debra Burnet, a daylighting designer and specialist on the impact of daylight on human health and well-being, noted in Construction Specifier, “Daylight is a drug, and nature is the dispensing physician.” We need that drug, even in our bedrooms.

Biophilia

The term Biophilia was coined by psychologist Erich Fromm and popularized by E.O. Wilson in his 1984 book “biophilia.” It means "love of life" and suggests that there are significant health benefits to being able to see plants and trees. I thought it all a bit touchy-feely until I interviewed architect Tye Farrow, who studied neuroscience as well as architecture and writes:

"Experiencing nature—in ways as simple as a stroll in the woods—is proven to improve physical and mental health in myriad ways. The natural experience lowers blood pressure, reduces heart rate and muscle tension. It reduces anxiety, increases emotional resiliency and boosts the sense of well-being. Architecture and design that is inspired by nature and the natural world can bring these health-promoting advantages to visitors. Examples include the use of natural light, natural materials, and shapes and structures that are reminiscent of natural spaces."

See my interview of Tye on Youtube here.

Other social and psychological functions of windows

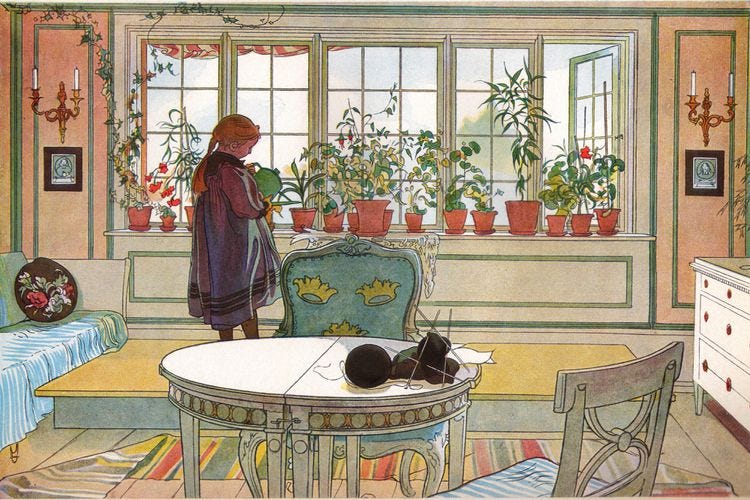

A wonderful Swedish study published in Buildings and Cities—"Windows: a study of residents’ perceptions and uses in Sweden"—looks at the many roles that windows play and the way people use them, exploring "daylight, the visual connection to the outside and the role of windows in the home during the day and night." It found that windows connect us to our community and society.

"Windows, transparent in both directions, enable the environmental conditions (social connection) to support the basic need for relatedness. For example, by following ‘window blind etiquette’, people show they care for others or want to be accepted by others. Autonomy is represented by participants’ own decisions on when to adjust daylight controls (blinds, curtains, external shades) to improve sleep, daylight or privacy.

I covered this in greater detail in Treehugger here.

Solutions: 1. Frame the windows

This is where it gets complicated. We want to reduce the window-to-wall ratio but still have acceptable aesthetics. I wrote earlier in Treehugger that I loved what PietriArchitectes did in Aubervilliers, France, putting a picture frame around the small windows. Picture frames have historically been considered an enhancement; picture frame historian Suzanne Smeaton wrote that “design elements echo and reinforce composition.”

Architect and passive house consultant Rob Harrison did this in the Park Passive House in 2013 by NK Architects, who wanted a big vertical window. Rob wrote: “I proposed, and as you can see, NK Architects executed my idea of chamfering a set of deep-set punched windows instead of the tall fixed window on the bay, using CFC-free polyiso to maintain a decent average R-value in the assembly."

If you can’t get the window proportion you want, there are still tricks like Mikhail Riches with Cathy Hawley pulled off with the Stirling Prize-winning Goldsmith Street project. RIBA noted: "To be certified Passivhaus, the windows had to be smaller than the proportion in a Georgian or Victorian terrace, so the architects have used a set-back panel around the windows to give an enlarged feel.”

Solution 2. Rethink our standards of beauty

When I first saw Architype Architects’ Callaughton Ash, an affordable housing project, I thought it demonstrated how simple forms and careful window choices were the solution to building efficient, affordable homes. The windows varied in size, and placement was determined by what was happening inside, not how it looked from the outside. I wrote in my review of the project:

“Windows are such an important architectural and aesthetic element, and hard to do when you are limited by cost and the math of Passivhaus, especially when starting with a box; it takes a good eye to pull it off. But instead of treating a window as a wall, as so many modernists do, think of it as a picture frame around a carefully chosen view. Or, as Nick Grant suggests, "size and position are dictated by views and daylight."

Back in the day when we had Twitter, I would have applied Bronwyn Barry’s hashtag, #BBB- Boxy But Beautiful.

Evelyne Bouchard of Tandem Architecture Ecologique gets this too; I wrote for Green Building Advisor: “Bouchard admits that most of her houses look similar on the exterior, i.e., “kind of boxy.” They are all about 20 to 24 ft. deep to allow the low winter sun to hit the back walls, and there are no fancy details. She also points to the asymmetrical window layout, saying she designs from the inside out.”

Windows are hard.

I have often written about windows and always try for a boffo finish. I can’t think of a better one than I have written before, so from my Treehugger post, Windows are Hard.

“The rules haven't changed in 500 years:

Keep the windows as small as you can get away with and still let in the light and views you want, with an eye for proportion and scale. And keep it simple.”

From my Treehugger post, Is LED Lighting More Energy-Efficient Than Daylighting From Windows?

“The Turkish playwright Mehmet Murat Ildan wrote, “Your desire to be near to window is your desire to be close to life!” They are wonderful things that should be in every habitable room. But we should measure their impact in well-being and happiness—not watts or lumens.”

From Green Building Advisor’s Rethinking Window Size:

Windows are complex, multifunctional, carbon-intensive, expensive, difficult to get right, and too often, designed primarily for aesthetics. I concur with the findings of professors Richardson and Coley: We must change how we look at the aesthetics of buildings and “drive a revolution in what architects currently consider acceptable for how houses should look and feel. That’s a tall order, but de-carbonizing each component of society will take nothing short of a revolution.”

Ali Heshmati of Henning Larsen Architects left a long comment on LinkedIn that I thought should be published here:

Lloyd Alter, I enjoyed your article on "What is the purpose of a Window?" on Carbon Upfront! Especially when it came to the history of window and glass itself. I do however, as an architect and a researcher on the impact of light on human health take issue with two parts of your article. This is with outmost respect for what you have been doing and that I am a follower of yours and respect your ideas.

In any case, in the "Light" portion of your article you mention that we could get away without as LED these days can provide sufficient light. I am of course, paraphrasing! Later in "Circadian Rhythms" part you passingly mention the impact of light on circadian rhythms and ultimately health which is greatly appreciated. I also understand that Carbon Reduction is your main preoccupation which we share.

I respectfully but strongly want to disagree with you on size of windows and the amount of natural versus LED light we need and can use.

Most of chronobiological, neurobiological, and neuroscience studies in the last 25 years, show that almost all built environment is overly dim during the day and overly bright at night. Now, this is due to the fact that we did not know about the mechanism of photoentrainment of the circadian system which needs intense light at early hours of the day and almost total darkness at night. Most of our light environments, today, are designed for vision. Visual photoreceptors need very little light and can process that light in milliseconds. Take moonlight for example, one can see one's shadow walking in the moonlight which has intensity of less thank one lux of light. Now, consider our evolutionary conditions of solar irradiance of 100,000 lux by midday and almost total darkness at night. These are conditions that gave birth to our biology. So, the scientific recommendations today for light for health is around 250 MEDI or Melanopic lux which is around 800 lux from some other source of light. Now even the plane glass cuts 30% of incoming light. Add number of codings and shading devices we use in architecture, even when we have full glass walls, we get very little light inside.

Therefore Daylight and window size matter.

What about fire escape? Even in modern houses, tragedies happen and an egress in a bedroom can be the only option.