"The most sustainable building is one too beautiful to tear down."

Mariusz Hermansdorfer of Henning Larsen tells us to not be so carbon-brained.

For many years I have quoted Steve Mouzon’s four attributes of sustainable buildings from his Original Green Foundations:

“Buildings should be Lovable because if they can't be loved, they won't last. They should be Durable in order to carry their lovability deep into an uncertain future. They should be Adaptable because if they endure, they will need to be used for many uses over the centuries, some of which don't even exist today. They should be Frugal because energy hogs will be very difficult to sustain long into an uncertain future.”

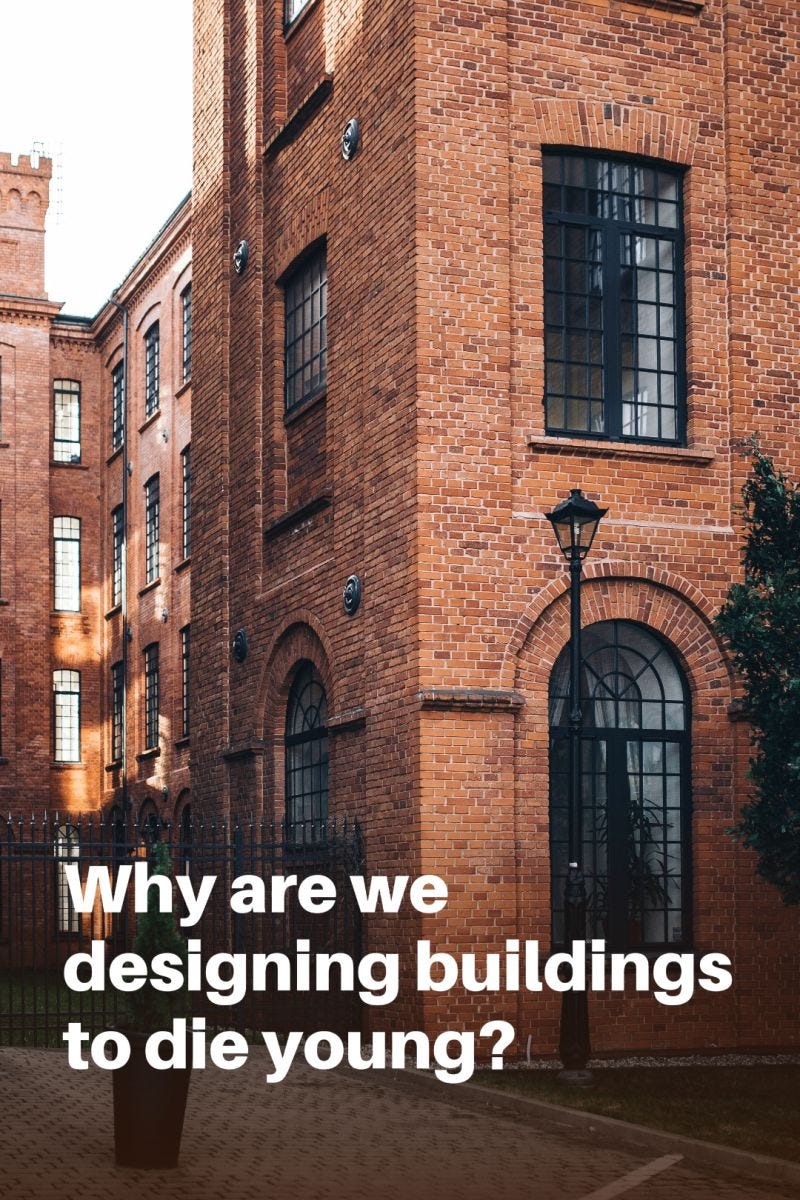

I thought of Steve as I read more recent words from Mariusz Hermansdorfer, Head of Computational Design at Henning Larsen. His Linkedin post starts with a question: “Why are we designing buildings to die young when European cities prove they can live for centuries?”

Hermansdorfer explains that Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) calculate carbon emissions on a per square meter basis, so architects have a “perverse incentive” to reduce floor-to-floor heights, using less material for columns and exterior cladding. They are also making windows smaller because they have higher upfront carbon emissions than walls.

These all sounds like wonderful examples of sufficiency to me, using less of everything from pipes to elevator cables, what’s not to love? Hermansdorfer explains:

“Daylight performance collapses. A 2.7m ceiling with 30% glazing admits 60% less natural light to the back of a 6-meter-deep room compared to 3.2m ceilings with 40% glazing. This forces occupants to use artificial lighting for 4-5 additional hours daily – often erasing the supposed carbon savings within just a few years of operation.”

I might argue that point; LED lighting is efficient and electricity sources are decarbonizing, and bigger windows mean more heat loss or gain, so I doubt the the carbon savings are ever erased. But I can’t argue the next point:

“Health and wellbeing deteriorate. Poor natural lighting disrupts circadian rhythms, increases depression rates, and reduces cognitive performance. Lower ceilings create environments that elevate stress hormones and reduce productivity.”

This is a subject I discussed recently in the post, Low-E coatings on windows save energy but may be messing with our health, which I now think buried the lede in the title; it’s not just coatings but also window size. I also quoted Ali Heshmati of Henning Larsen, who explained why “Daylight and window size matter.” Two years ago I wrote in Green Building Advisor: “Windows are carbon-intensive and a source of air leakage, so let's make them smaller” But Heshmati explained, “Most of our light environments, today, are designed for vision” when we need far higher lighting levels for our health.

Then Hermansdorfer raises another point that resonated:

“Future flexibility vanishes. That ground floor designed for retail with 2.7m ceilings? It can never become a restaurant, co-working space, or workshop. We're locking in obsolescence from day one. Meanwhile, European cities prove buildings can reinvent themselves for centuries. Amsterdam's 19th-century warehouses, originally built with 4-5 meter ceilings for cargo storage, now house everything from luxury lofts to tech offices to art galleries. Berlin's former department stores from the 1920s seamlessly became co-working spaces and apartments. Barcelona's industrial warehouses transformed into trendy mixed-use developments.”

This hits on the arguments for built heritage preservation, most recently in Strategies from the Sufficiency Toolbox: Flexibility, which specifically mentioned how “Many 19th-century warehouses were flexible and were converted into lofts and offices.” Over the years I have written that heritage preservation is climate action and that our heritage buildings aren’t relics from the past but are templates for the future, because they were, using Mouzon’s terms, lovable, durable, adaptable and frugal. Hermansdorfer is suggesting that we learn from these buildings and build what I have called “new-old buildings,” and sounds very Mouzonian in his conclusion:

“But there's a deeper truth here: the buildings that survive aren't just functionally adaptable – they're designed with care, proportion, and beauty that makes demolition feel like vandalism. Cities preserve what they love.”

”The most sustainable building is one too beautiful to tear down.”

Mariusz Hermansdorfer’s little Linkedin post comes at a time when I have been reconsidering some of my thoughts about sustainable design. Where my mantra for the last few years has been “use less stuff,” I have learned from Lisa Heschong and Ali Heshmati that when it comes to windows, perhaps we need a bit more.

Now I have learned from Mariusz Hermansdorfer that when it comes to full Lifecycle Carbon Assessments, we shouldn’t “make design choices that prioritize short-term carbon accounting over long-term livability.” We might need a bit more ceiling height, and a lot more beauty.

I often quote Steve Mouzon and Carl Elefante when discussing built heritage and reducing carbon emissions, but I suspect I will be quoting a lot more Mariusz Hermansdorfer.

More reading about windows (some of which I am rethinking)

Why we need “windows with purpose” As the world heats up, we have to rethink how we design them, especially in multi-family dwellings.

The new manual: What is the purpose of a window? Do we need them at all? If so, how many and how big?

Rethinking Window Size Windows are carbon-intensive and a source of air leakage, so let's make them smaller.

Is LED Lighting More Energy-Efficient Than Daylighting From Windows? Windows should be designed for well-being and beauty, not watts or lumens.

Windows Deliver a Lot More Than Just Light and Air A Swedish study finds they have important social and psychological functions.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ).

Great article, Lloyd! I appreciate the framing of our pursuit for lower carbon buildings in this holistic way. Two related sources that come to mind : Stuart Brand's "How Buildings Learn" (which I bet you've seen), and "Vital Architecture" by Ruud Roorda. The high road / low road dichotomy in Brand's is illustrated well by your writing, but your discussion of windows and health is a unique take that adds more strength to the conversation.

Great article as always Lloyd.

I've been thinking a lot about the quantifiable/unquantifiable thing a lot recently.

It seems to me that many of us have been using a rational/scientific/modernist approach to warning about the issues with climate change for many years without any success.

And one of the major gripes I have with passivhaus (which I'm very much a fan of in principle) is just how spreadsheet-y it is and how many of its proponents will tell us how great their buildings are because the air infiltration rate is a few cubic millimetres lower than standards whilst ignoring the fact that their buildings look hideous. My argument isn't that we shouldn't do passivhaus, but that we should be doing it at the same time as designing buildings that are brilliant in all the other ways by which we define good architecture. Too many passivhaus architects are not good designers and too many good designers aren't interested in passivhaus because it boxes them in to designing in a very prescribed way.

I don't know if you're familiar with the Scottish writer and academic Iain MacGilchrist and his writings on right brain/left brain thinking (if you're not, take a look - he's brilliant) but his most recent substack post is titled 'quantity kills'.

And of course there's the wonderful old quote from Louis Kahn (a right brain thinker if ever there was one) about architecture moving from the unquantifiable to the quantifiable and then back to the quantifiable.

If we're relying on left brain maths/physics to tell people how good our buildings are, or to inspire them to action against climate change, I just don't think it's going to work.