Sufficiency vs abundance: Less is more vs Less is a bore

The fundamental problem with the abundance doctrine is that it takes too much stuff. It’s all about “more” when we have to think about less.

See a special subscription (free book!) offer at the end of the post!

Everybody is talking about Abundance, the new book by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, and its thesis that we can have “the future we want” with affordable housing, clean air and water, supersonic weekends in London, all powered by geothermal, nuclear and renewables, with AI and other technologies lifting billions out of poverty, if we just let builders build and inventors invent.

The book started with an abundantist vision of the future in 2050. In a previous post, How to build a world around sufficiency or "frugal abundance" I developed an alternate 2050 vision of a world based on sufficiency, looking at housing, water, and food, and noted at the end that I would next look at transportation, energy, technology, and work. It’s a vision based on the thesis that we have to use less stuff, that making stuff without cooking the planet with upfront carbon emissions is hard, and that we have to spread what we have more equitably. Here are my further thoughts from 2050 (remember, this is science fiction, just like the book Abundance.)

Transportation

This section really shouldn’t be here, separate from housing; in 2050, we remember the lesson learned from a consultant named Jarrett Walker that “Land use and transportation are the same thing described in different languages.”

Back in 2025, 74% of North Americans lived in “suburbs” and drove private cars everywhere; 27% of vehicle miles travelled were commuting between houses and workplaces, 22% for shopping and errands, and the balance for social or recreational purposes.

But as we noted earlier, in 2050 we mostly live in multifamily buildings in 15-minute cities built to “the Goldilocks Density” which can support shops within walking distance. The futurist Alex Steffen once noted, “There is a direct relationship between the kinds of places we live, the transportation choices we have, and how much we drive.” With the kinds of places we live, we don’t have to drive at all. Why bother?

Then, there was the micromobility revolution of e-bikes, cargo bikes, and a Cambrian explosion of innovative vehicles that cost far less than cars, needed far fewer resources, and could easily handle the distances that needed to be covered in a 15-minute city. Given how rarely they were needed, it made far more sense to share cars than to own one. Most of the time, bikes and e-bikes were sufficient.

For longer trips, we rebuilt intercity tram lines and glorious high-speed rail.

The Abundantists once promised jetliners that “routinely reach Mach 2—twice the speed of sound—using a mix of traditional and green synthetic fuels that release far less carbon into the air.” Alas, flying at Mach 2 needed five times as much fuel per passenger, and making e-fuels was incredibly energy-intensive. Today, flying is much like it was before the jet age: expensive and slow, and only used between continents.

Work

In 1928, John Maynard Keynes predicted that because of a predicted eightfold increase in productivity, we would be working on average three hours a day by 2030. He thought it would make us better people:

“We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin.”

The abundantists, Klein and Thompson, thought technology would let us work less as well, writing in their version of 2050:

“Thanks to higher productivity from AI, most people can complete what used to be a full week of work in a few days, which has expanded the number of holidays, long weekends, and vacations. Less work has not meant less pay. AI is built on the collective knowledge of humanity, and so its profits are shared.”

Klein and Keynes were both wrong; we got less leisure and less pay. As Lloyd Alter wrote in Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle,

According to Benjamin Freidman, it’s because of inequality. Basically, all the gains from the increases in productivity went into the pockets of the rich. He quotes economist James Meade, writing in 1965, discussing how having more time would have the opposite effect:

Meade instead thought “wages would thus be depressed,” as ever less labor was necessary for production. Correspondingly, an ever greater share of total income would go to the owners of the machines. In the absence of government-provided welfare on a massive scale, therefore, most of the workforce would be compelled to take whatever low-paying jobs they could get, presumably in the service of the machine-owners but not working with the machines. In Meade’s vision, “we would be back in a super-world of an immiserized [impoverished] proletariat of butlers, footmen, kitchen maids, and other hangers-on.”

Fortunately, we didn’t fall into this trap; we taxed the rich at Eisenhower-era rates and used that money to reduce inequality. Also, there are better jobs than that today. We are farmers. We fix things and keep them working far longer than they used to. We are miners working through the dumps of the last century, finding the metals and plastics that can be recycled. We are millions of cottage industries, working in our homes or on top of the shop. And, of course, there are still jobs that require a human touch in health and child care.

And we don’t need as much money in the first place; back in 2025, a car cost $15,869 per year to maintain. Our Passivhaus homes cost next to nothing to heat or cool. We grow much of our own food and don’t buy a lot of new clothes.

Technology

Even our websites are solar powered, inspired by the work of Kris De Decker thirty years ago, when he wrote:

“The Internet is not an autonomous being. Its growing energy use is the consequence of actual decisions made by software developers, web designers, marketing departments, publishers and internet users. With a lightweight, off-grid solar-powered website, we want to show that other decisions can be made.”

Phones remain a problem, but most of us use dumb ones now. After Elon Musk made Neuralink chip implants compulsory, many of us revolted against being wired full-time into Grok AI and X and ripped them out, vowing never to be slaves to technology again.

The Abundantists Klein and Thompson wrote that “technology is at the heart of progress, and always has been.” However, we learned that progress can be like that Mach 2 jet- technologically sophisticated, but it serves only the very rich, and the environmental cost is too high. We had to dial it back a bit.

Everything is connected

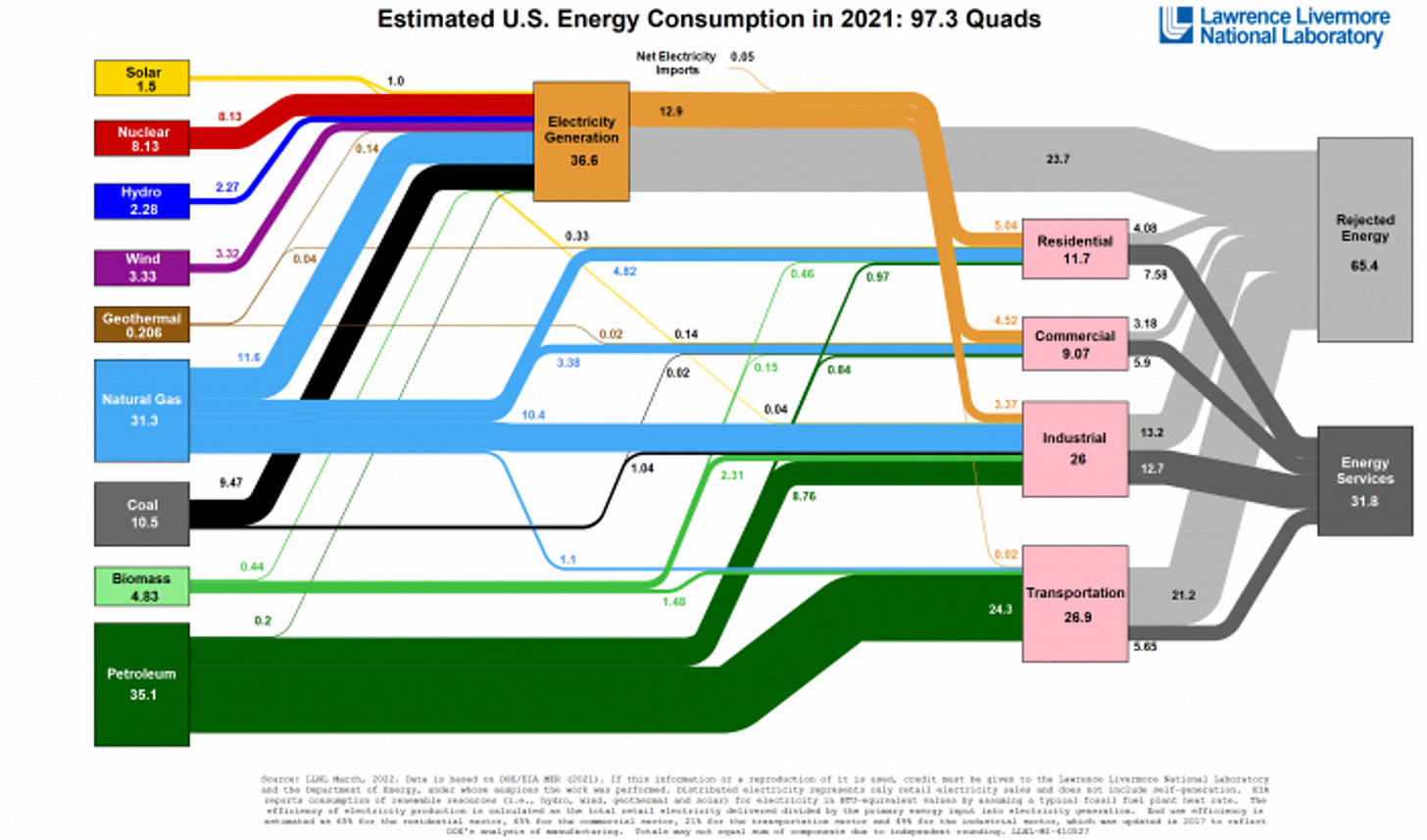

It’s shocking when you look back 30 years and see where our energy came from and where it went. The graph is very different today!

Because of the design of our communities, we don’t need cars, and the few that we have are electric; that big green band of petroleum goes poof.

Because our buildings are made of wood and straw to Passivhaus standards and run on heat pumps, natural gas was eliminated.

Because half of steel goes into cars and the other half into buildings, the main industrial uses of coal and gas are gone, we just recycle steel and aluminum now.

Because solar panels and batteries got so cheap, we just wallpaper every surface facing the sun with them and have more than enough electricity to feed our e-bikes and tiny heat pumps.

But most importantly, we live in a world based on sufficiency instead of endless growth. Yamina Saheb defined it:

“Sufficiency is a set of policy measures and daily practices which avoid the demand for energy, materials, land, water, and other natural resources, while delivering wellbeing for all within planetary boundaries. Sufficiency bridges the inequality gap by setting clear consumption limits to ensure a fair access to space and resources.”

Samuel Alexander was more poetic:

“The fundamental aim of a sufficiency economy, as I define it, is to create an economy that provides

‘enough, for everyone, forever.” In other words, economies should seek to universalize a material standard of living that is sufficient for a good life but which is ecologically sustainable into the deep future.”

The fundamental problem with the abundance doctrine is that it takes too much stuff. It’s all about “more.” Klein and Thompson concluded:

“We seek a politics of abundance that delivers real marvels in the real world. We want more homes and more energy, more cures and more construction. This is a story that must be built out of bricks and steel and solar panels and transmission lines, not just words.”

The sufficiency doctrine is about “less.” Less pollution, less inequality, less waste, less needless consumption. OK, maybe more of some things, as J.B. MacKinnon wrote:

"The evidence suggests that life in a lower-consuming society really can be better, with less stress, less work or more meaningful work, and more time for the people and things that matter most. The objects that surround us can be well-made or beautiful or both, and they stay with us long enough to become vessels for our memories and stories. Perhaps best of all, we can savour the experience of watching our exhausted planet surge back to life: more clear water, more blue skies, more forests, more nightingales, more whales.”

See Part 1: How to build a world around sufficiency or "frugal abundance"

And my earlier version: How will we live in 2050?

Special offer!

My book, Living the 1.5 Degree lifestyle, was all about limiting my carbon emissions to the level we had to average per capita in 2030 (2.5 tonnes). The 2050 target is even more dire, at 1 tonne of carbon per capita. It is a template for a sufficiency lifestyle, and in the face of the Abundance doctrine onslaught, it is more relevant than ever.

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$34.95 ) If you live in London or Glasgow, I will bring them personally in late May, and we can arrange a pickup.

I just came inside from going outside to hang laundry. The wind is blowing, should dry in an hour, no energy use. Birds entertained me the entire time. Three species of woodpeckers, cardinals, tufted titmice, some unidentified warblers, mockingbirds sowing confusion about identification, catbirds, brown thrashers, chickadees, wrens, sparrows (three species), robins, blue jays and blue birds. Sufficiency is fun, as is electric biking (too many hills here for commuting on a regular bike). Your vision of the future not dominated by stuff is much more palatable than the abundance. Who needs it when you are surrounded by life?

Your posts always give me hope. They also reinforce my inclination to make do with what I have, and to encourage others to do that same. Thank you. Please continue.