How to build a world around sufficiency or "frugal abundance"

Part One of a series in response to the book Abundance.

I was going to write a review of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book “Abundance,” but there is already an abundance of them. I could point out the inconsistencies, fundamental problems and errors, but where do you start? With the second paragraph of the 2050 fantasy that the book starts with?

“You open the refrigerator. In the fruit and vegetable drawer are apples, tomatoes, and an eggplant, shipped from the nearest farm, mere miles away.”

No! You never put apples and tomatoes in a drawer together; apples release ethylene gas, which will spoil the tomato, which shouldn’t be in a fridge in the first place. It is a silly, minor complaint, but they pile up so fast. Let’s instead go to the first sentence after the 2050 fantasy:

“This book is dedicated to a simple idea: to have the future we want, we need to build and invent more of what we need. That’s it. That’s the thesis.”

The future we want. That’s a phrase I have heard before, from Elon Musk back in 2018 when he launched his solar shingles. His idea of the future we want was a big suburban house with a solar roof and a Powerwall battery in the garage, along with a Tesla car. It would be very nice, a future that many might want. But it’s not a future we can have.

But the problem, as I wrote at the time, is that it doesn’t scale. There is not enough land, there is not enough lithium, there is not enough money to build the future we want for more than a few rich people. More importantly, there is not enough headroom in the carbon budget to build the future we want. Klein and Thompson don’t see these limits or the problems. They never mention the words “embodied carbon” but a shitload of it will be emitted building the future they want. They do mention that “By 2050, the world will need to permanently remove 10 billion tons of carbon dioxide from the skies every year to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change,” quoting the IPCC, without counting how much upfront carbon their vision will add to that already impossible number- there are no “factories that slurp pollution from the sky.”

Ultimately, we do not have the resources or time to build “the future we want” and should be thinking instead about the future we need. As geologist Simon Michaux has noted,

"Replacing the existing fossil fuel powered system (oil, gas, and coal), using renewable technologies, such as solar panels or wind turbines, will not be possible for the entire global human population. There is simply just not enough time, nor resources to do this by the current target set by the world’s most influential nations. What may be required, therefore, is a significant reduction of societal demand for all resources, of all kinds. This implies a very different social contract and a radically different system of governance to what is in place today.”

I have written a book about this, and I suspect that Abundance sells more copies in one minute than I have in total; it’s not nearly as exciting. Thinking about the supply of all that cool new technology is much more fun than reducing demand for what we already have. As engineer Nick Grant has noted,

My hunch is that the world is divided into “less is more” demand-

side people, who focus on reducing their demand for emissions-heavy products and processes, and “less is a bore” supply-side people, who look for solutions within the sector that emits them—it is a personality trait.

In my previous post, How will we live in 2050? I quoted the Australian philosopher Samuel Alexander and his vision of a different model for the future:

"This would be a way of life based on modest material and energy needs but nevertheless rich in other dimensions—a life of frugal abundance. It is about creating an economy based on sufficiency, knowing how much is enough to live well, and discovering that enough is plenty.”

In my book “The Story of Upfront Carbon,” I built on Alexander’s “envisioning exercise intended to explore what living sustainably actually means in an age of limits” and developed my own vision of a future based on sufficiency, on “how a life of just enough offers a way out of the climate crisis.” In my last post, I looked at a day in the life of my granddaughter Edie in 2050; since Klein and Thompson started with a 2050 fantasy, I will continue in that mode, looking at how we will live, eat, move, and work.

Housing

Housing was a major issue in 2025; in North America, it was expensive and time-consuming to build and operate and was in short supply. As the climate heated, we learned that much of the existing housing stock was in the wrong place, became uninsurable, and often overheated. There was great demand for new housing in the northwest, the Great Lake states and provinces, in Maine and in the Maritimes.

The abundance people wanted less regulation and control; the sufficiency people wanted more- they saw what happened in Toronto in the seventies, and in New York in the forties when governments invested in building housing. The key word there is invest; as Cherise Burda noted in Spacing, “The non-profit and co-op housing sector relies primarily on loans, not subsidies, which providers pay back to the government.”

It was clear that the North American model of car-dominated sprawl didn’t work anymore, so planners looked to Europe, and Vienna in particular. As Lloyd Alter wrote in Azure Magazine, “in 1923, the Social Democrat government approved a plan to build 25,000 housing units; they were paid for by taxes on luxury goods, traffic, land and even brothels.” The government kept building, making land available through Bauträgerwettbewerbe (housing developer competitions). Building codes encouraged relatively small buildings with single stairs. Few people owned their apartments; Alter explained:

“Eighty percent of Vienna’s population rents, and for good reason: They have security of tenure that is almost equivalent to ownership. Rents are relatively low, 60 per cent of units are subsidized and there are no year-to-year leases. Tenants can stay in their apartments forever, even if they started in subsidized units, and can hand them down to their children. The mix of families on full, partial and zero subsidies in the same buildings rarely leads to conflict because multi-unit residential communities across the entire city reflect an assortment of different incomes.”

In 2050, building this way ensures that the density is high enough to support retail on the ground floor and public transit connecting it to the city and other developments. A vast multimodal transportation system promotes e-bikes and cargo bikes. Nobody needs cars or drone deliveries when everything is so close. Some called it a “15-minute city.”

The buildings are all built to the Passivhaus standard for energy efficiency and resilience, from natural materials such as wood and straw, and powered by renewable energy.

However, we realized years ago that it wasn’t enough to think about efficiency or renewables; we had to use less stuff. We had to think about sufficiency as well because, as Samuel Alexander noted, “efficiency without sufficiency is lost,” and renewables are wasted.

Units are sufficiently sized; a look at Paris or Milan showed that people happily raised families in 700 to 1000 square feet; location mattered more than unit size, the park was your backyard, the theatre was your media room. Every study showed that compact little buildings cost the least to build, used the least materials, and had the smallest environmental footprint, and soon the world looked like Vienna.

Water

Water became a serious issue as the climate heated; the Abundance people thought they would use nuclear power to desalinate seawater, but this wasn’t necessary; so much of it was wasted or mismanaged. In California, for example, only 10% of water was piped to humans, while 80% of managed water went to agriculture. 20% of that went to almonds, and 27% went to feed crops for livestock. Smart reallocation of the resource dramatically reduced the need for water.

In cities, trillions of gallons of water were lost through leaky infrastructure. In Toronto, for example, the city loses anywhere from 10 to 15 per cent of its total drinking water supply to leakage each year, or about 103 million litres per day.

We didn’t need fancy desalinization plants; we just fixed the pipes and figured out how to use much less water. Today, we collect water from our roofs and grey water from our sinks for use in our community gardens, and use tap water only for drinking, cooking and washing.

We don’t flush drinking water down the toilets or have black water contaminated by human waste; years ago, engineers and agronomists realized that we couldn’t afford to waste the phosphorus in pee or the nitrogen in poop when fertilizer was being made from fossil fuels. All our buildings now have centralized composting toilet systems to collect the stuff that is not human waste; it’s a valuable resource.

We found that if we practiced sufficiency, if we just used less water instead of wasting it on lettuce and toilets, we were just fine.

Food

Back in 2025, the abundance types projected that we would get our fruits and vegetables from vertical farms and our chicken breasts and ribeye steaks from cellular meat facilities. But they soon found that growing food indoors required buildings, lights and lots of electricity, while the sun is free and “a teaspoon of healthy soil contains more microbes than there are humans on this planet.” Outside of Singapore or marijuana grow-ops, indoor farming never worked out.

Besides, we grew lots of food. In the USA, 40% of it was wasted; in Canada, as much as 50%. Up to 13% of fruits and vegetables went unharvested due to labor shortages or market price fluctuations; Much of it was lost in the supply chain, because of aesthetics, or because of overpurchasing by consumers. In Indonesia and Malaysia, 20% of the rice crop was eaten by rats. Globally, 2.5 billion tonnes of edible food was wasted or lost every year.

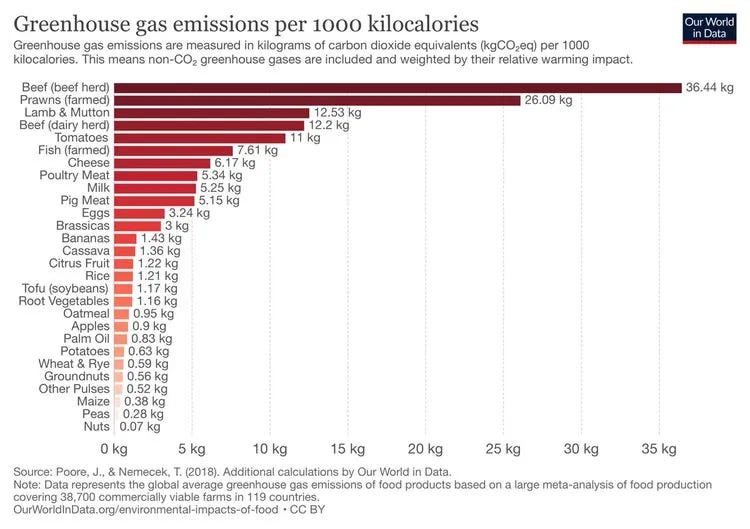

It’s not that we didn’t have enough; it is was a broken system where we grew lettuce in California which is 94% water and ship it in refrigerated trailers so that we could eat a limp salad in February. As my favourite website noted, lettuce is stupid. So is the supply chain of refrigerated containers and warehouses with emissions grossly underestimated by people like Our World in Data who neglected to count refrigerant losses.

Then people used to drive giant “sport utility vehicles” to Walmart and buy enough food for a week, much of which rotted at the back of the giant doublewide fridge. The whole system was full of economic distortions, waste, pollution and emissions.

Today we no longer ship food all over the world, but grow it locally, it’s not a hundred-mile diet but a hundred-yard diet, where everyone has a garden plot or buys from the local farmers. We shop like many Italians, where you go to the store every day and buy what you need for dinner. We eat with the seasons; when we finally have a local strawberry explode in our mouth, it tastes so much better than the California one did. We eat more root vegetables, more coleslaw instead of tossed salads.

Preserving has become a major preoccupation , giving us a taste of fruit or tomato in the off-season.

Meat remains a serious problem; people like it and are loath to give it up even in 2050. But this is very much a cultural thing; after the Second World War, the American Meat Institute had to run ads to promote eating beef because people had got out of the habit due to rationing.

But there’s meat and there’s meat; beef emits the most carbon, uses the most feed, the most land, and the most water. Many people have switched to chicken and pork and are eating it less often, especially since the carbon taxes make beef so expensive.

In fact, before the real costs of water and carbon were factored in to prices, food was extaordinarily cheap for a long time, dropping from a quarter of a family’s disposable income to less than 10%. It’s hard to imagine that the 105-year old seven-time American president was elected 25 years ago because of food prices; they are much higher now that all the externalities and carbon taxes are factored in.

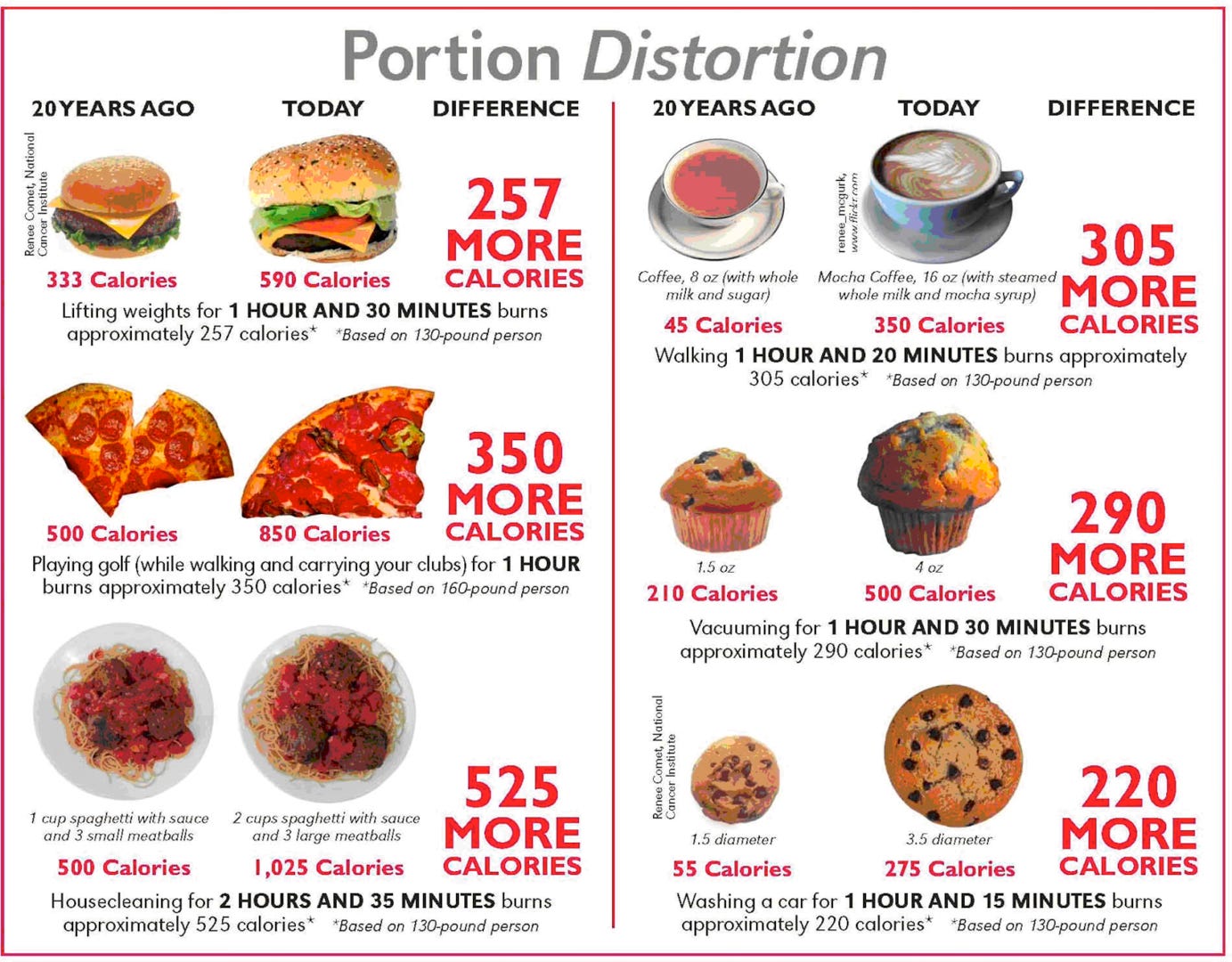

Because food was so cheap, people ate a lot of it, and portions sizes exploded; just cutting back to portion sizes from 2000 has cut consumption of meat and other foods almost in half, bringing costs back down.

In the end, we didn’t need fancy hydroponics and lab-grown meat; we used sufficiency instead of technology. We made appropriate choices about what to eat, how much to eat, and when to eat it. This made all the difference.

Next: transportation, energy, technology, clothing, and work.

"105 year old seven time American President" *gulps*

A lifestyle based on having enough is one that I live. I simply cannot understand a need for constantly striving to have more.

I do not own a car. I use public transportation. I see big pickup trucks and SUVs with only one person, the driver, in the vehicle all the time. Greed, a need for status, and willful blindness to the folly of such is one explanation for that, I guess. How big of a vehicle is truly necessary?