Nice Shades: A UK design guide for exterior shading should be used everywhere

You should keep the heat out in the first place instead of relying entirely on AC.

In his wonderful book Going for Zero, Carl Elefante writes in the introduction:

“Despite forty-plus years of so-called energy-conscious design, the built form and façade configuration of very few buildings respond effectively to their solar orientation, the most basic and effective strategy for reducing energy demand. Architects have abdicated their design authority to engineering and technology… Operable windows, shutters, and awnings are anathema to engineering principles that rely on sensors and algorithms. In the name of energy conservation, building and energy codes favor sealed buildings that require constant and continuous energy use to remain habitable. It is insanity.”

In an article for Treehugger, Architect Michael Eliason complained that we just don’t get it in North America.

“Unfortunately, there is effectively no active solar protection industry in North America. Power outages will increase in the future, especially during heat waves. How will building occupants keep cool when they cannot even keep the sun out of their buildings? Operable external solar protection offers a level of climate adaptiveness that planners and policymakers need to be thinking about in a warming world.”

That’s why this Shading for Housing: Design guide for a changing planet is so interesting and timely. It’s written for the UK market and commissioned by the blind and shutter industry and the Good Homes Alliance, but it’s still relevant and applicable in the North American market.

I have written previously about how awnings were common before air conditioning; they were everywhere, even on Toronto’s trendy Queen Street West. But with AC, you don’t have a fiddly awning; you simply pay for the electricity to remove the heat once it gets inside. Nobody much cared about keeping it out in the first place.

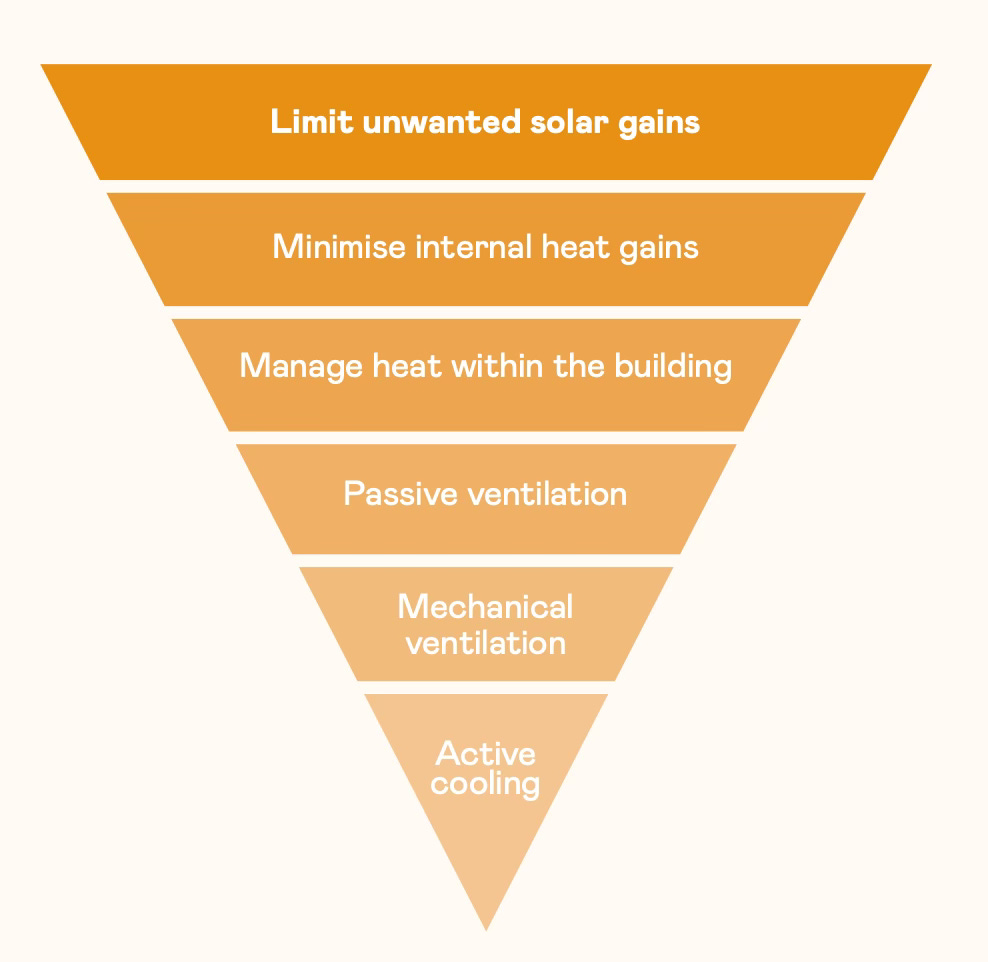

But making that electricity costs money and results in carbon emissions, and as the world gets hotter, those summer peak loads are going to be getting harder to cope with. That’s why this cooling hierarchy makes sense, and why you start with limiting unwanted solar gains. It also makes a lot of sense with existing housing stock, much of which was designed for a different climate:

“A recent study shows that by the middle of the 2030s, 90% of the UK housing stock will suffer from overheating. Simply put, our built environment – designed for dampness, breeze, rain and mild heat – is in no fit state to shelter us from this changing climate.”

Conditions are similar in much of North America, where many homes and apartments lack air conditioning and are now suffering in the summer.

So why don’t people invest in shading? The design guide notes:

“Too many stakeholders see shading products purely as a maintenance cost; a ‘cold climate’ outlook which considers shading products as superfluous still prevails, while open-ended legislation encourages smaller windows instead of proposing external shading products. For many, the upfront cost remains a significant barrier, despite the mechanical ventilation and cooling savings that early shading design integration can provide.”

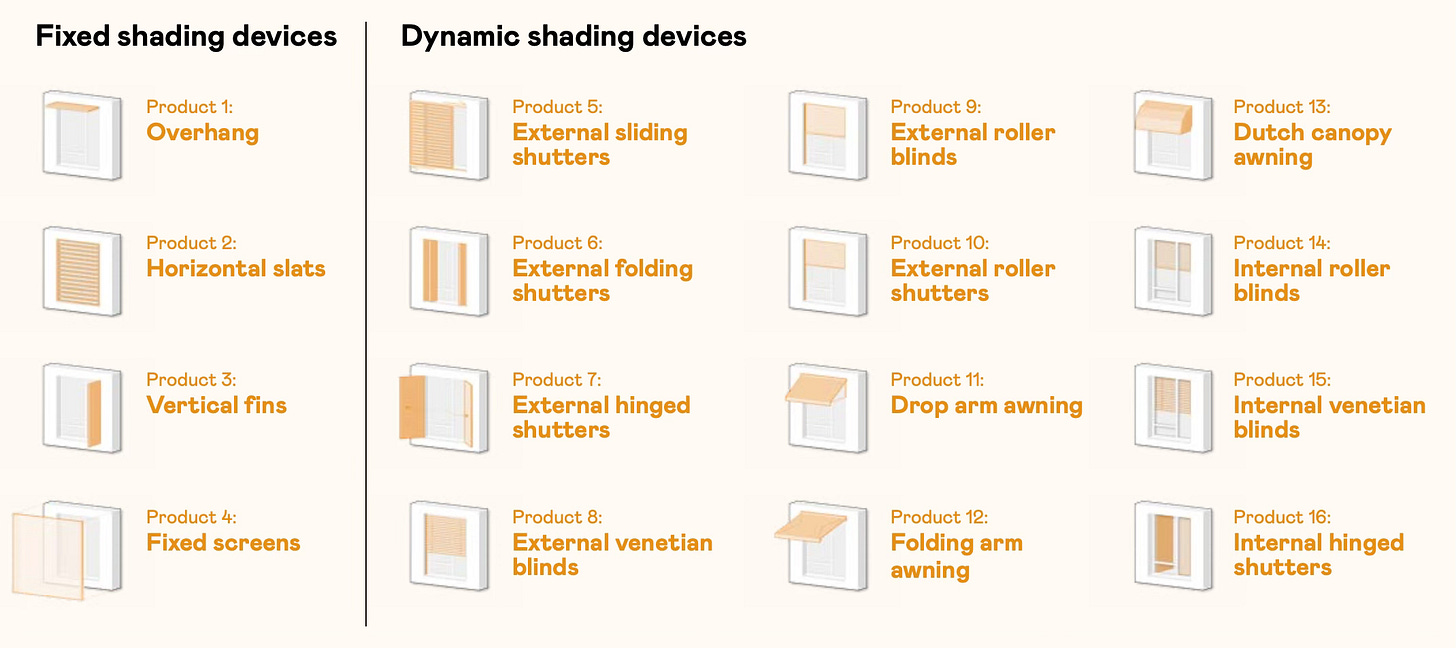

The guide shows a lot of dynamic shading devices, which is not surprising given who the sponsors are, but I am partial to fixed devices that are less complicated and likely less expensive, although they don’t work very well on west-facing walls.

Here is an example, Mikhail Riches’ Goldsmith Street housing, where you can see the shade cast by the fixed shading devices.

Here’s a version on a much larger scale, where Stas Zakrzewski put them on his Passivhaus tower in New York City.

As I noted in the heat of last summer, we used to know how to do this. We can do it again, using this guide which calls for “a design culture in which the everyday specification of shading products on domestic buildings – or the designing for shading from the start – is second nature among developers, housebuilders, architects and consultants.” Download it here.

I have written many articles here and previously on Treehugger under the heading “Nice Shades:”

Nice shades: Beat the heat with awnings

Nice Shades: This NYC Passivhaus Condo Has Terra-Cotta Baguettes

Nice Shades: Inside and Outside Merge in Australian Courtyard House

Nice Shades: Bogotá School is Clad in a 'Wonderframe'

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ).

What about deciduous trees in the yards of one-story and two-story houses and buildings? They block and soften the sun in summer and let the sun shine in during winter.

The 1963 Victor Olgyay book “Design With Climate” has a wonderful chapter on solar control that includes an easy to read graphic chart that shows different shading techniques and their effectiveness. The book should be an essential reference for students and designers.