More lessons from Canadian small house designs

You don't need a thousand square feet per person to live comfortably.

I recently wrote about how the Canadian government is developing house plans for the 21st century, and promised that I would move on from the 1947 competition to the wonderful 1965 book of small house designs that I have treasured for years. I love these plans because they show a different way of living, before bathrooms and kitchens took over our houses and added so much cost and complexity, but I certainly don’t believe that plan books will solve our current housing crisis; we don’t need more single-family houses built on farmland, which is pretty much what these books are about.

Neither does Allan Teramura, a past president of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada. He writes in the Globe and Mail that while these pattern books were useful at the time,

“Today, the situation is far more complex. Rural land adjacent to cities is largely in the hands of developers, who have a pre-established model for exploiting its commercial value, which does not include one-off, nonmarket projects. Providing them with templates they can copy-and-paste into place is not likely going to change that. Inner-city infill sites, on the other hand, are all unique, and cannot be retrofitted with prototypical buildings.

Teramura notes that we need strategies for dealing with exclusionary zoning, intensifying existing neighbourhoods and redeveloping moribund strip malls and other under-utilized sites, and increasing energy efficiency to the Passivhaus standard.

But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be looking at the fundamental questions of design. As architect Andy Thomson noted in LinkedIn,

I STILL think the reboot is a fantastic way to explore solving the problems we face wrt resilience, performance, climate mitigation and economic growth/degrowth. The Feds, by providing the right answer to the wrong question have inadvertently exposed the raft of problems we are facing, and I think today's architects are incredibly well suited to both unpack and resolve these questions - if only we were at the table!

So let’s get back to the 1965 book of small house designs. I believe it’s important to look at them to see where we have come from and how home design has changed and certain aspects have gotten out of control.

My poster child for what’s wrong is this so-called 3400 square foot retirement home built by Taylor Morrison in Florida, with three bedrooms, two and a half bathrooms and three kitchens: a fancy open kitchen with a giant island, a “messy kitchen” where you have all the stuff you actually use, where you nuke your Lean Cuisine and toast your Eggos. Oh, and then there is a big outdoor kitchen. Again, this is a home for retirees, probably two people.

Let’s compare it to one of my favourite houses from the plan book, this almost lavish three bedroom house by FW Hunter and DL Sawtell of Vancouver, built around a patio with a sunken living room, a single kitchen partially open to the dining room, and it even has a walk-in closet in the master bedroom. The bathroom is broken up so that two people can use it at the same time, and there is a utility-laundry room off the kitchen, all in 1270 square feet. Seriously, if you were getting older, would you want three kitchens to manage? Eight sinks to clean? Kitchens and bathrooms are the most expensive rooms to build and the hardest to maintain, yet that’s where all the change is from 1965 to 2020. They are both still just three bedroom houses.

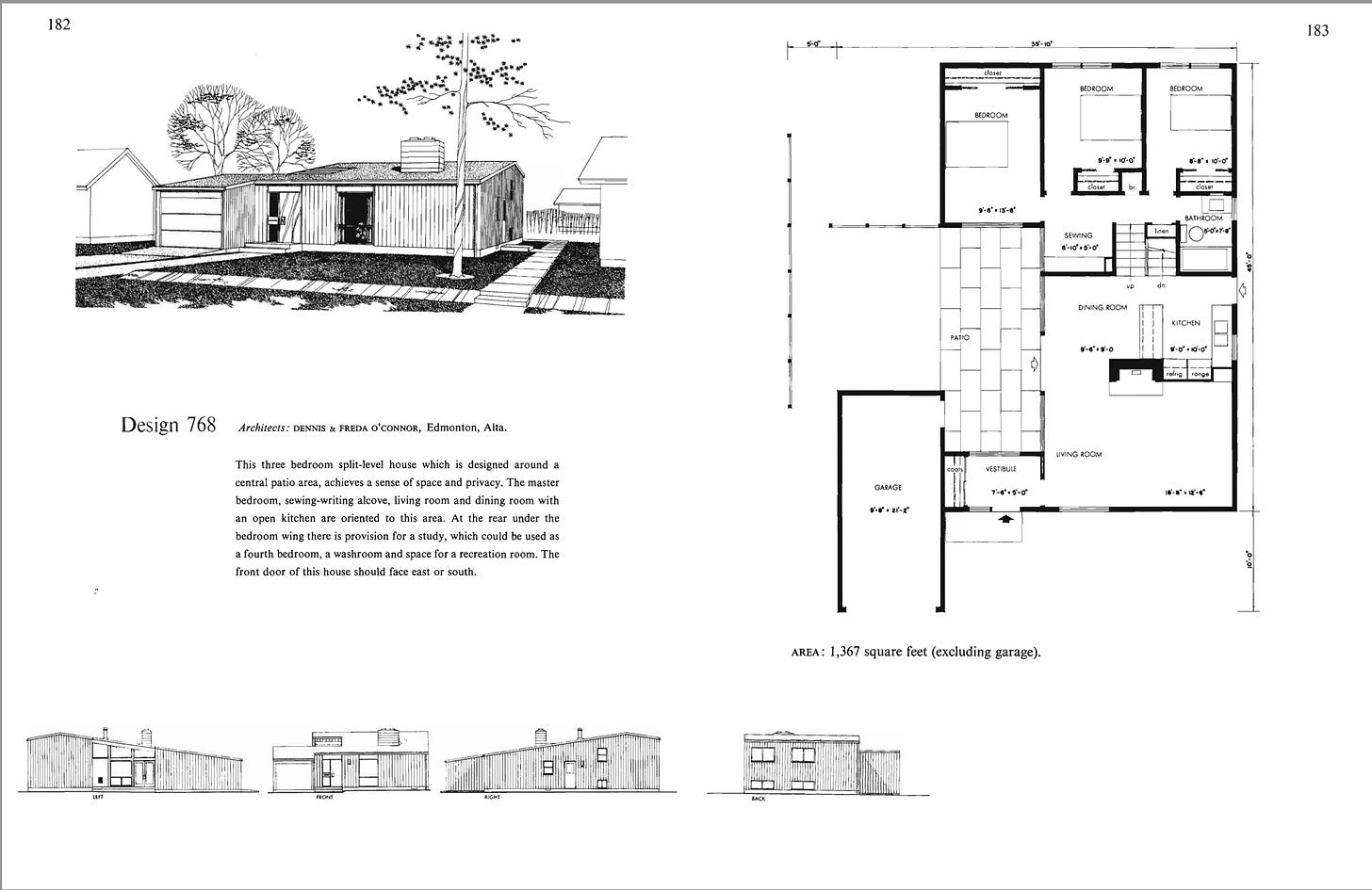

Since we are talking fancy plans built around patios, have a look at this one designed by Dennis and Freda O'Connor of Edmonton. It’s the only male/female team in the book. Freda O'Connor"was the first woman elected to Alberta Association of Architects, 1966, and was an early example of a spousal partnership, with Dennis O’Connor." According to another Edmonton architect, "Freda kinda gave the women’s movement a little jolt when she came, because she was upwardly mobile and she was going to do as well as any man.” Their firm continues today as Maltby & Prins Architects.

Here’s another interesting house by the O’Connors. It's a raised bungalow so that lower level is bright and useable, but upstairs, the plan is split with kids' bedrooms on one side, master on the other. This is very common in apartments now but was probably unheard of in the mid-sixties. Turn that washroom into a full bath (and how about a coat closet?) and you have a real liveable house here.

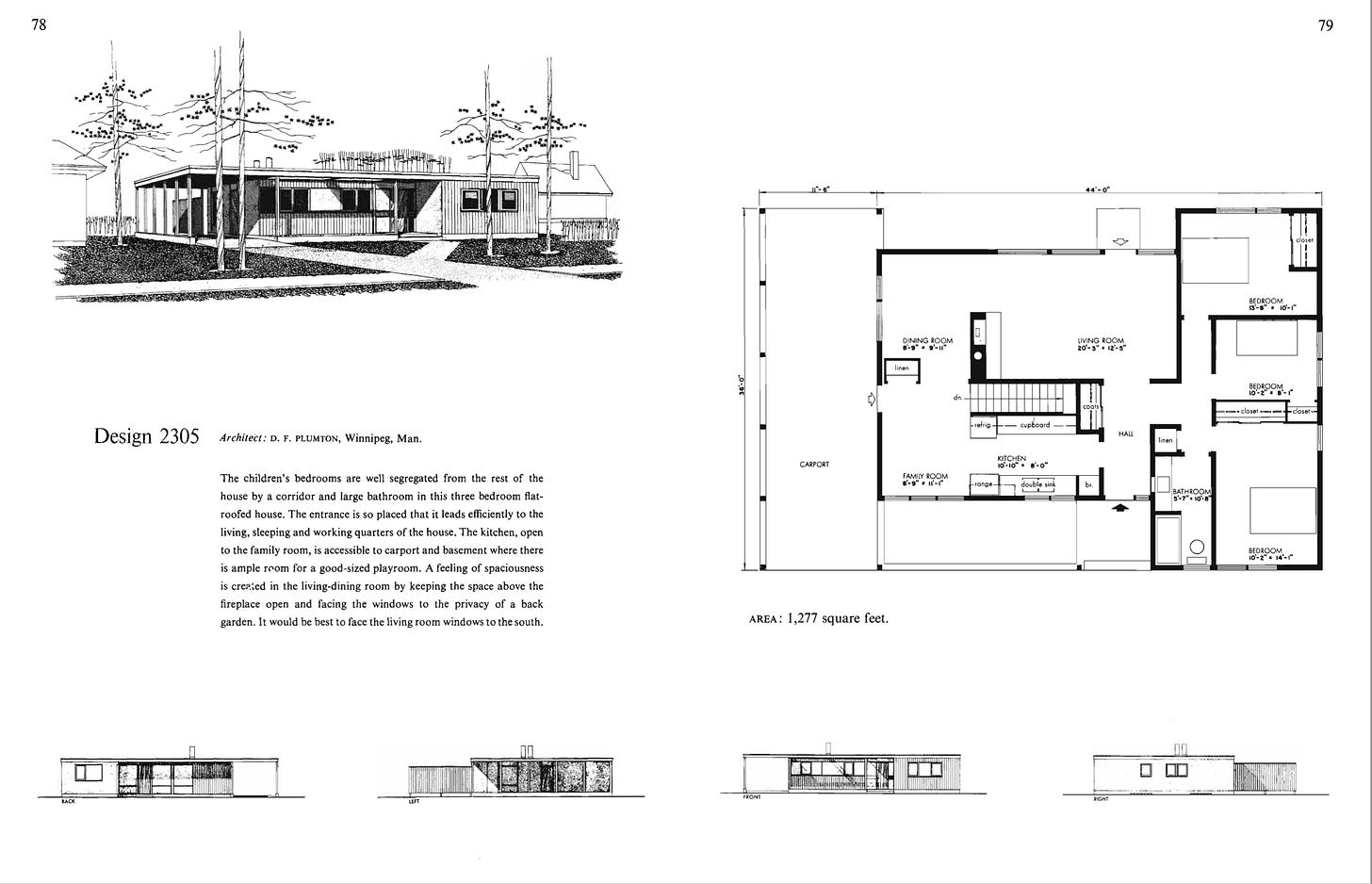

These houses have grown since the 1947 plans, and often have family rooms and even second baths. But they all have classic U, L or Galley kitchens. I don’t know how people raise kids now in completely open kitchens where they can run around everywhere, where there is no delineation of spaces. Or where you have big islands covered in dirty dishes while you are trying to eat, which is why the messy kitchen was invented.

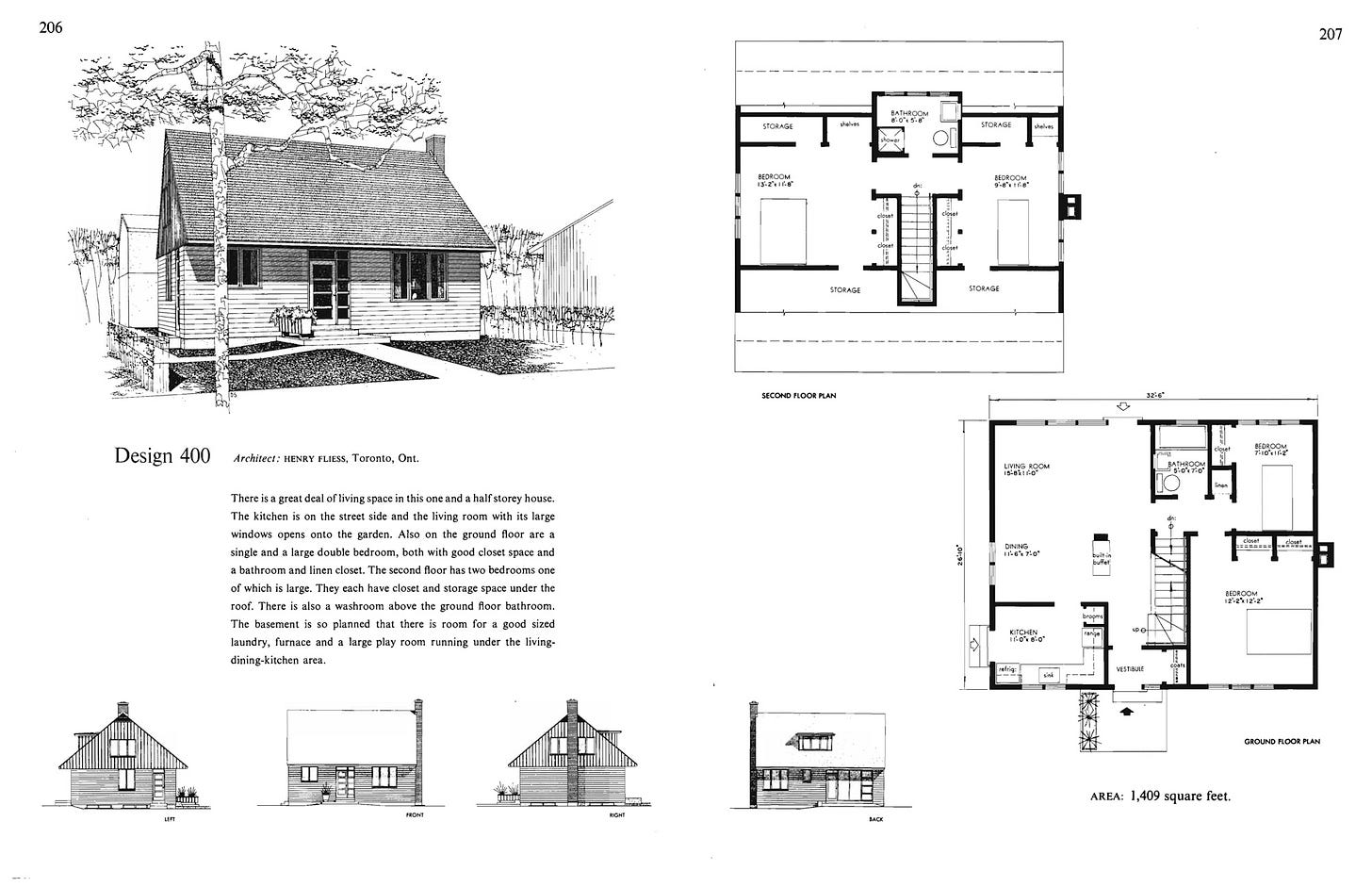

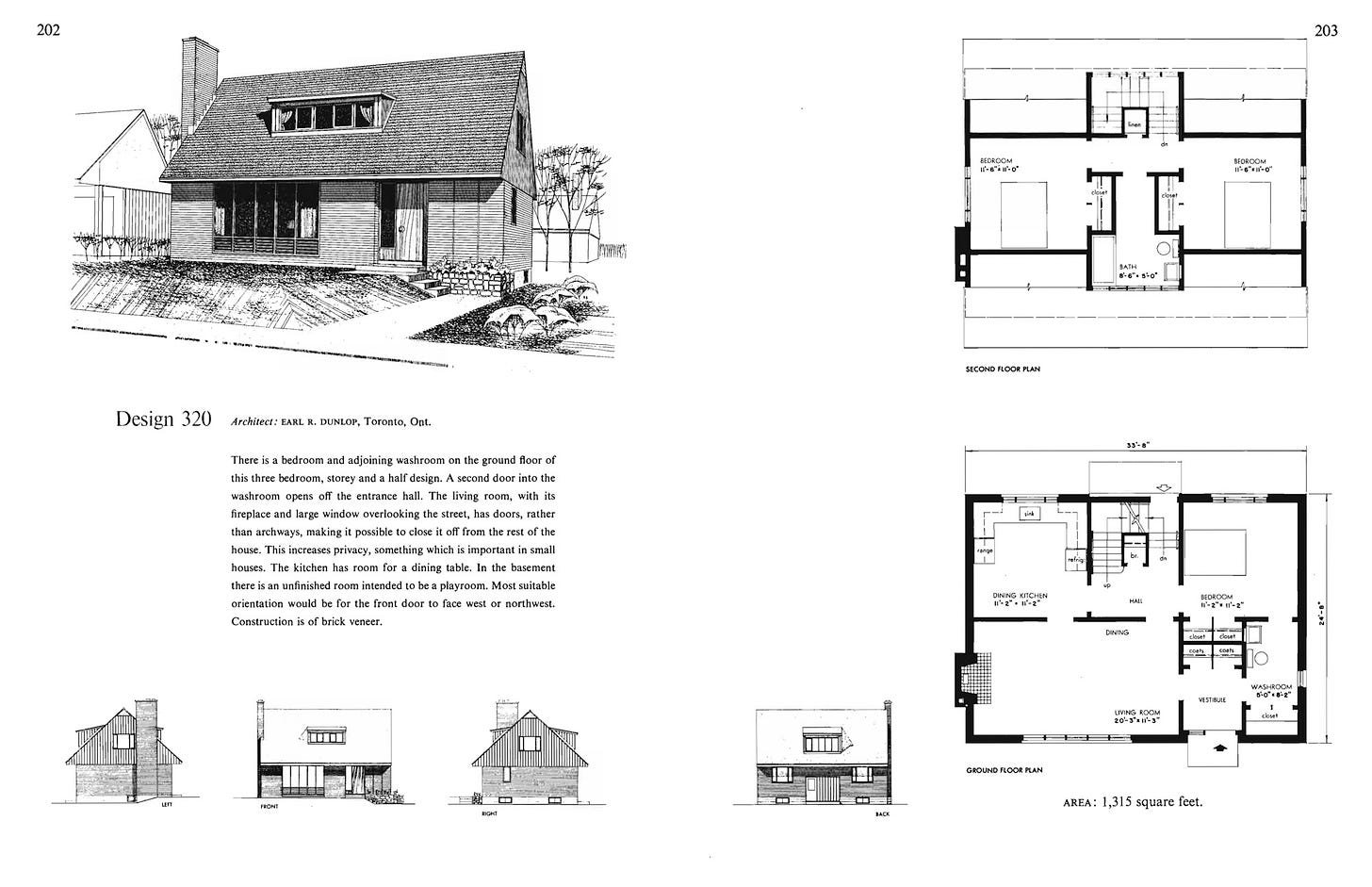

Bring back the 1-1/2 Storey House

One of the most common designs in postwar housing was what was called a 1-1/2 storey house, with the upper level built into the roof. They were very economical to build, since there’s nothing cheaper than shingles. But they are also great designs if you are thinking of the family life cycle. As this design by Henry Fliess shows, you generally get a main floor bedroom and bath, then two bedrooms up in the roof for the kids. It’s got what you need when you are starting out with enough room to start a family, and with the bedroom and bath on the main floor you can stick around for a long time.

These all get knocked down now, which is a shame; in 2008, architect David Fujiwara worked on the Now House, a prototype for renovating a 1-1/2 storey house to near net-zero.

The steep roofs were at a great angle for solar power, both thermal and electric here. The house was full of foam and still had natural gas (hey, it was 2008) but Now House notes: “In reducing energy consumption, the house has reduced its contribution of greenhouse gas emissions by 59%, or almost 6 tons per year. Electricity use is reduced by 60%.The Now House has demonstrated that energy independence is possible for existing single-family homes, even in a cold climate.”

It’s funny that just about everything that was written about this house has been scrubbed from the internet but the first thing that popped up on search was my interview of David Fujiwara, which looks like it is the first time I ever held a camera. At about 3:50 I start asking if he thinks people can live in such a 1300 square foot house in an era when most houses are twice the size. David notes that they did drop the basement floor to make it more liveable. They considered adding more floor area but realized that “a small house is better for energy efficiency.”

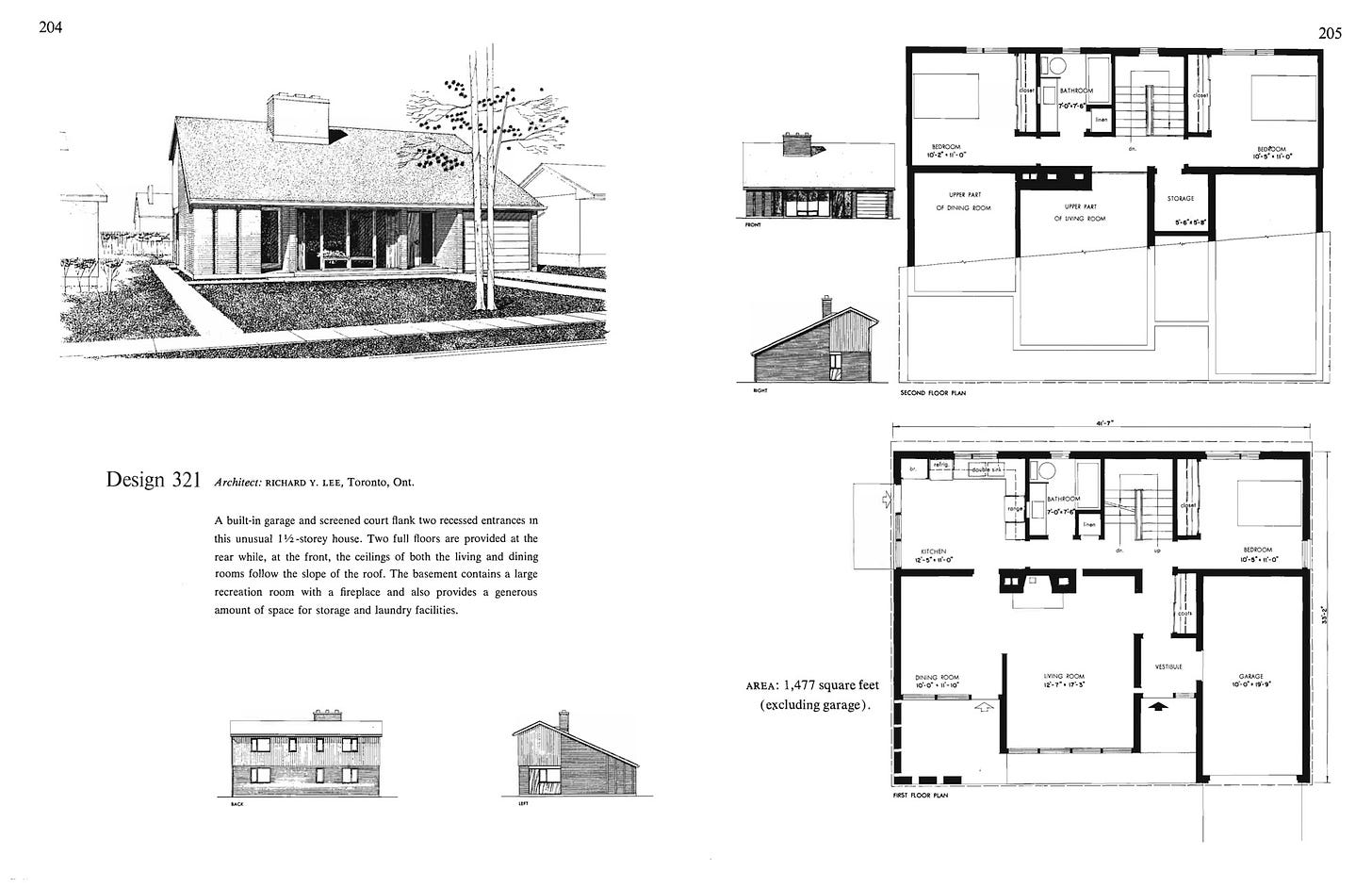

This design by Richard Lee is relatively large at 1477 square feet but look at that living room with the cathedral ceiling and the overlook from the second floor above. You have a kitchen big enough for a table but also a nice dining room with a view and a door into an exterior court that might have a breakfast table. These are generous rooms, yet the “basement contains a large recreation room with a fireplace and also provides a generous amount of space for storage and laundry facilities.”

CMHC brought in different architects from all over the country and showed many different ways to design a home, many of which would be perfectly comfortable and adequate for families today. I can see this one coming out of a modular home factory and others stacked up into triplexes. We may not need a lot of single family house plans these days, but we do need creativity, efficiency, and sufficiency, building no more than we really need. This is the real lesson of the CMHC plan books.

When I bought my 864 ft2, 1929 Inglewood house in Calgary in 1981, I learned that it had been enlarged in 1960 by Bruno and Maria, postwar Italian immigrants, by adding 10’ (240 ft2) to the back and excavating a basement by hand, with buckets. Two adults, five children, one small bathroom. In 1981 Inglewood was considered a slum, but I met everyone on the street almost immediately, knew their names and bits of their histories.

Inner city neighbourhoods being the low-hanging fruit for densification, I now know no one on the street other than my next door neighbour, an original postwar German immigrant family. There are now many new two-storey infills, one or two people in them with at most one child who no one ever sees. As you point out Lloyd, it is the expansion of bathrooms and kitchens that means that what was an 800 ft2 house across the street with two people in it, is now a 5500 ft2 house with two people in it. It isn’t densification as much as it is largification.

Upshot, maybe, is that no one has to rub up against, or make way for, anyone else, even within the family. Civility on the decline.

Great read Lloyd. What happened in the last 50-60 years? These designs are fantastic. Building these types of family homes to net zero operational emission standards, with low carbon building materials is the only way forward.

I live in a 100 year old 1 1/2 story heritage style home. Needs an energy retrofit which will commence shortly and happen over time. Low carbon materials of course. Its more than enough for us.

I also like the idea of stacking the last design into a triplex.

Thanks you for sharing