Canadian government to develop house plans for the 21st century

Their house designs from after the Second World War introduced a new generation of architects.

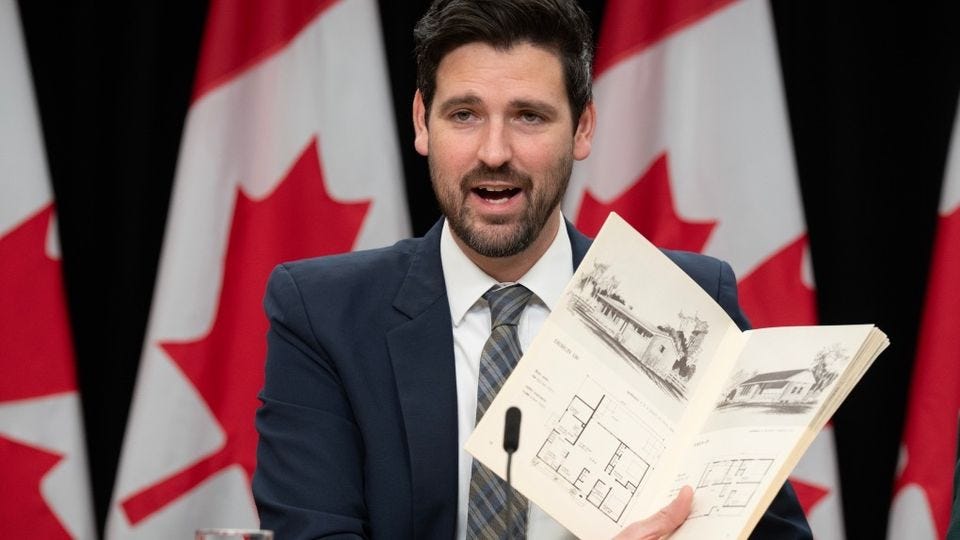

It’s Canadian Content Day, as Sean Fraser, the Minister of Housing, has announced the Ministry will develop a catalogue of pre-approved plans to speed up building approvals and production. This was done after the Second World War by the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and continued through to 1974. The Minister says, “We intend to take these lessons from our history books and bring them into the 21st century.”

Sean Fraser totally makes sense in this video, noting that they won’t look like the plans of the Victory Homes of the past. “We might use modular, panelized, mass timber, even 3D printing. But if we are willing to learn from the lessons of the past, we can identify solutions that will solve the housing challenges that Canada faces today.”

If they do this right, it could be brilliant. Hire good architects, set high standards for efficiency but also sufficiency- what do people really need? These are some of the lessons that can be learned from these plan books, which were about more than just houses, but also about developing a distinctly Canadian culture and identity.

Many of these houses were simple and tiny, and some were architectural gems. In her thesis, Building small houses in postwar Canada: Architects, homeowners and bureaucratic ideals, 1947-1974, Ioana Teodorescu argues:

“The postwar houses, despite their small size, are a major arena for the expression of modernism defined as it were by ideals of an egalitarian democracy and by scientific rationalism embraced by Canadian leaders at the time and projected unto the Canadian society. In this respect, the CMHC catalogues were vehicles to educate and convince ordinary Canadians of the values of modernism.”

She also notes that “In a postwar Canada obsessed with detaching itself from Britain and creating new national ways in almost every field, it is not surprising the CMHC advisers militated for national schemes which would support a Canadian identity from an architectural perspective.”

Some were designed by in-house architects and some by young architects who would go on to greatness. Some were the results of architectural competitions, and some were invited; one from the late ‘50s said if a plan were accepted for inclusion, the architect would be paid C$1000 (serious money- according to the Bank of Canada calculator, that’s C$10,366.01 today.) CMHC would then sell the working drawings for ten bucks and send the architect another $3.00. Or the public could just look and learn, as noted in a 1958 book: “Whether you intend to plan and build your own individually designed house or whether you are "window shopping" in the local subdivisions, it is hoped that this book will help you as it has helped others.”

There are about 35 plan books on the Canadian government site, all uploaded to the Internet Archives by scruss, but I have looked closely at the 1947 competition and the 1965 Small House Designs book that I have owned since the ‘70s. Let’s look at the 1947 competition in this post and the 1965 version tomorrow. This is updated and expanded from a Treehugger post I wrote a few years ago.

The 1947 competition problem was to design a home for “Mr. & Mrs. Canada,” described in Magdalena Miłosz’s essay Simulated Domesticities: Settings for Colonial Assimilation in Mid-Twentieth-Century Canada as “a white, heterosexual couple with two children, who exemplified the national ideal of the homeowning family.” According to the brief:

"They have no preference concerning style but dislike the freakish or the bizarre or picturesque. They are very interested in contemporary ideas of utility and livability and would like "built-in furniture" but do not want "gadgets." They want a well-lighted and healthful interior and are interested in the trend to larger glass areas. Since their budget is carefully planned, heating and maintenance costs should be at a minimum. They have no objection to departures from traditional materials provided their architect can assure them that the new ones he suggests will give just as good service.”

Conditions and tastes vary across the country, so the competition was broken into regions. The winner in the Maritimes was J. Storey; I wondered if this was Joe Storey, who was not a Maritimer and became a very prominent modernist architect in Chatham, Ontario. His daughter, Kim Storey, a prominent architect in her own right, confirmed:

"Yes, he was just out of school, won $500 and moved back to Chatham and set up his practice with the winnings!" When Kim was born, the local newspaper covered the event saying, "Local architect adds another Storey to his house". I wondered why he entered in the Maritime category- were the odds of winning better? Kim told me: "I don’t know—but I remember in the CMHC competition we entered in 1979, many architects cleverly entered the maritime and the prairies for that reason. Better prize money too! (We didn’t figure that out and got a ‘Mention’ in Ontario.) So my father may have been thinking along those lines."

Everyone seems to be playing this game; second prize in the Maritimes went to Michael G. Dixon of Ottawa. He went on to be the most prolific plan generator for decades, turning up in every plan book multiple times. According to his obituary, “Michael entered the McGill School of Architecture at the age of 16, graduating in 1936, at which time he won the Hugh McLennan Travelling Scholarship enabling him to tour Europe. He had a very distinguished career with the Federal Public Service and was President of the Ontario Association of Architects in 1970.” Dixon also won second prize in Quebec.

Third Prize in the Maritimes went to another Ontario architect, Kent Barker, who later unsuccessfully tried to teach me how to draw at the University of Toronto School of Architecture. I would have expected better drawing from him!

Architects in Halifax must have been really upset with all these ringers dropping in.

Going Maritime was clearly a smart move, given how tough the competition was in Ontario. The second prize in the Ontario region went to a 25-year-old John C. Parkin, just back from Harvard. His entry shows Dad coming home by helicopter. It has a tight, efficient plan, the kids' bedroom opens up with a folding wall, and a guest bed built-in beside the fireplace. Parkin went on to become one of Canada's most prominent and successful architects. He started his practice the same year as the competition; according to Wikipedia, by 1960, John B. Parkin Associates had grown to be the largest architectural firm in Canada.

Third Prize in Ontario went to Henry Fliess, who became one of the country’s best residential architects, designing much of the suburb of Don Mills. According to Dave LeBlanc who interviewed Fliess in 2006,

“He designed design Sherway Gardens (phases one and two) with fellow architect James Murray, as well as the Village Square in Baltimore's Cross Keys Village for influential American developer James A. Rouse. He also created about 15 designs for home in Don Mills, and as if to illustrate this, he fanned out on his teak dining table photographs of some strikingly modern beauties. In total, he estimates 300 to 400 were built, as well as a handful of custom one-offs near the Donalda Club.”

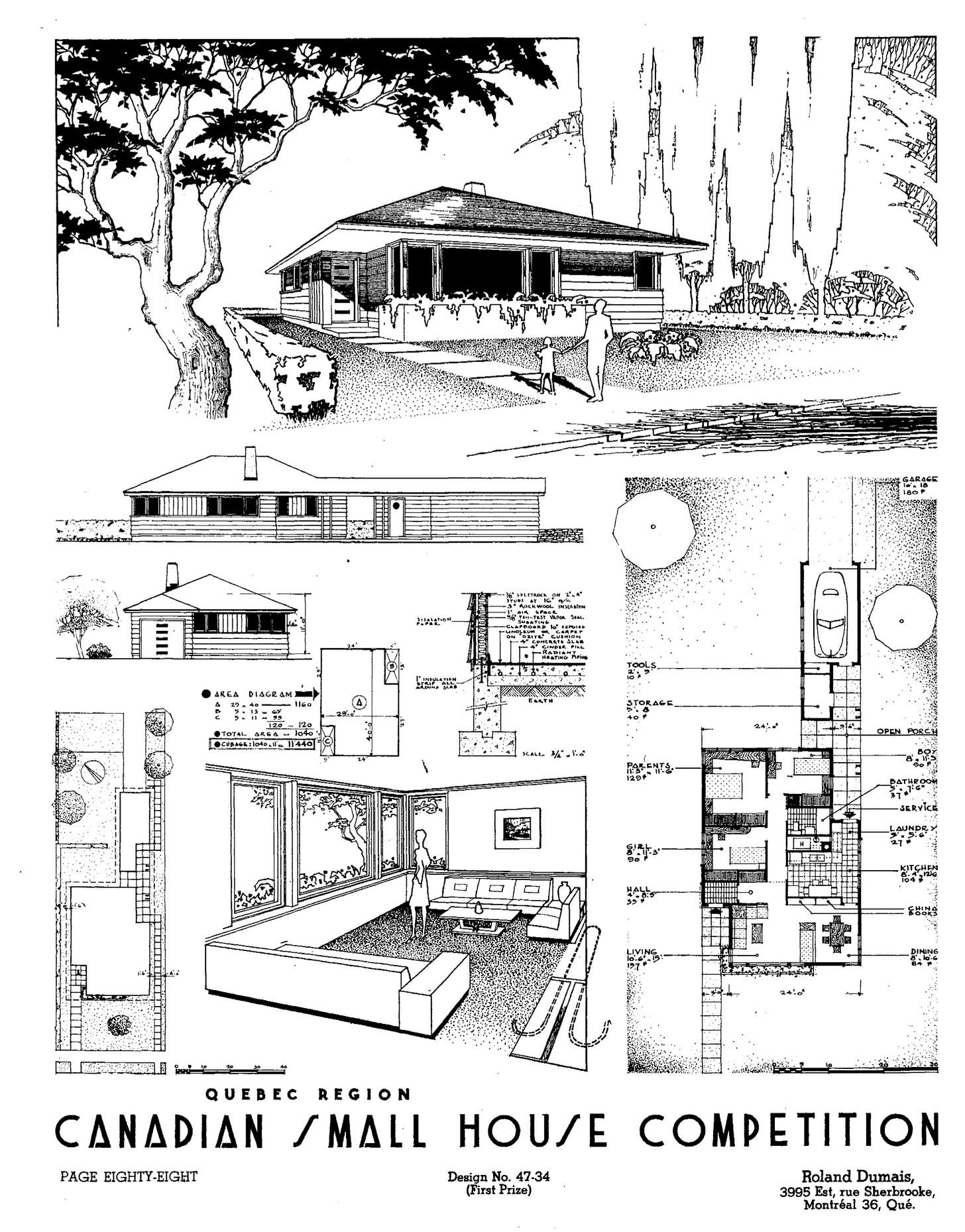

First prize in Quebec went to Roland Dumais, and it’s got some great things going for it. Unusually, it has no basement and radiant floors, a kitchen separated with a bookcase, and a definitely modern look. Dumais went on to design over 500 buildings and according to the CCA,

“Between 1940 and1960, Dumais focused on designing and building residential homes (villa, cottages, duplex, and triplex), apartment buildings, schools and churches. In the 1960s, Dumais’s projects diversified to include shopping centers, shops, offices and multi-purpose buildings. Dumais’s built projects are largely located in the Montréal area, but he also completed several projects in Repentigny, Châteauguay, and Berthierville. His most well-known built project to date is the École des Hautes Études Commerciales (HEC) (1967), located on Decelles Street in Montréal.”

Moving west, Andrew Chomick got first prize on the Prairies with a clever backsplit design that produces a very useable multipurpose space in the lower level, and for some reason, an elaborate closet system. He went on to do many houses in Vancouver which were published in “Low Cost House Plans” by his son, Steve Chomick. Surprisingly, none of the West Coast winners were very interesting, and none of the winners there show up on Google searches.

According to the Canadian Competitions Catalogue, the jurors were disappointed that “the elite of the architectural profession failed to show up” because everybody was so busy.

“Finally, the jury regretted that no new building techniques emerged from the competition. Besides, despite the jurors feeling disappointed by the limited attendance of experienced firms that "had been unable to contribute on account of the pressure of present business" they applauded the effort put forward by participants and claimed that "the first three choices in each Region would well provide the Canadian public with some novel and interesting designs for future house construction".”

But looking back, we got the best of the young architects just out of school, the likes of Storey, Fliess, and Parkin, all showing how much life you can squeeze into a thousand square feet. Everyone somehow got by with a single bathroom and tight, efficient galley kitchens.

Many of the designs hold up today; Charles Worsley’s design was probably too freakish or bizarre to win a prize, but architect Andy Thomson has updated it to modern materials. He kept it to one bathroom, telling me "we all grew up with just one bathroom, it is ridiculous now that in new houses, every bedroom has an ensuite!" He also complains, as I have, that "giant kitchen islands are consuming the house" and keeps a small, efficient kitchen. Buy it here.

Of course, the Conservatives are claiming that “Sean Fraser announced he’ll “persuade”builders to build communist style tiny wartime homes for young Canadians to be forced to buy.” That’s why I left Twitter.

But Minister Fraser is on to something here. Let’s find a new generation of Storeys and Parkins who kickstart their careers doing affordable designs. But we need more than plans; while we’re at it, let’s bring back CMHC funding for cooperative housing and maybe even co-housing and baugruppen. We’ve done this before; we can do it again.

Download your own copy of 67 homes for Canadians including Small house Competition here.

I am enthused. This is a great initiative and I am really happy to have found your article on it this morning! The caveat here is the implementation. My mind fills with great opportunities, but who is capable of collating the many attributes, many of which should be cutting edge?

There were some really smart people involved in this program then, while the issues were not the same then at all. Energy was to be used, colonialism was not at issue, singe family housing was a given, transport was cars, sewage went in a pipe, we could assume with 25 year max rainfall ...

I pray that the path will be well executed.

I really enjoyed this article! My parents were of the generation that built houses after WWII; these plans transport me to their homes. An uncle gave me his small-home idea books from the 1940s, and he remained intrigued by the Lustron home he visited in NYC, 1947(?). I've a picture of my cousins sitting at a fireplace much like the drawing in the 1st place winner. We had multiple bathrooms, however, and no coal bins. I'm a New Yorker yet lived in the Baltimore region for decades, which included ten years with Habitat for Humanity. We renovated row homes from ~1880 to 1915, with many on lots as narrow as 12'. James Rouse dedicated the first home I oversaw, and I was often at Cross Keys Village Square. Many Baltimore homes of the 1960s had radiant floor heating, generally hydronic, which generally failed by the 2000s. A few had heated ceilings--one had to be quite cautious when doing renovations.