Lindal Cedar Homes gives Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian homes a second life

These are wonderful designs, "translated" for the modern world.

Lindal Cedar Homes has teamed up with the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation to produce a new line of kit home packages, the Imagine Series, which “unite the enduring design principles of Wright’s Usonian homes with current developments in technology, construction and design theory.”

Twenty years ago, I worked with Royal Homes in Ontario to develop a line of small, modern modular prefabs designed by prominent living architects, with the intent of making good design more accessible and affordable. It didn’t work out; maybe I should have hired dead architects. But reading Lindal’s history, I see it faced some of the same issues and made the same mistakes.

Lindal, along with other pioneers like Acorn, (see At Home With Tomorrow: A look back at prefab in 1947) provides a package of building materials that are assembled by the purchaser, much as Sears Roebuck did 50 years earlier. Kits can travel farther and there are none of the building code and approval issues that come with modular.

Lindal was founded by Sir Walter Lindal (Sir is is first name, not a title). In a 2006 interview he explained how it started:

During the war, I saw how the Army could build encampments that housed 25,000 men in a season thanks to mechanized production and prefabrication. We don’t like that word because it denotes something cheap and shoddy, so we say precut. I thought we could use the same idea for packaged homes. I picked Toronto as Canada’s fastest-growing city. But it’s a solid brick town–they don’t build wood houses in the city. So we were relegated to summer cottages and country homes.

I live in Toronto and had the same problem..

We made some mistakes. We didn’t bend to trends that should have been obvious. We tried to keep prices down and build small. But that’s not what people wanted. They wanted to go big. They didn’t mind going into debt for 30 years. It wasn’t my instinct, but that’s what they wanted.

I found the same thing; all my plans were too small and missed the market. It’s why I am a writer today.

Lindal moved west and ended up in Seattle to become “the largest North American manufacturer of custom post-and-beam homes made of cedar and other quality materials. We help you design and build your home, using an efficient and predictable kit of premium materials that can be delivered worldwide.”

Most of their homes are their own designs, but there is so much to learn from Frank Lloyd Wright.

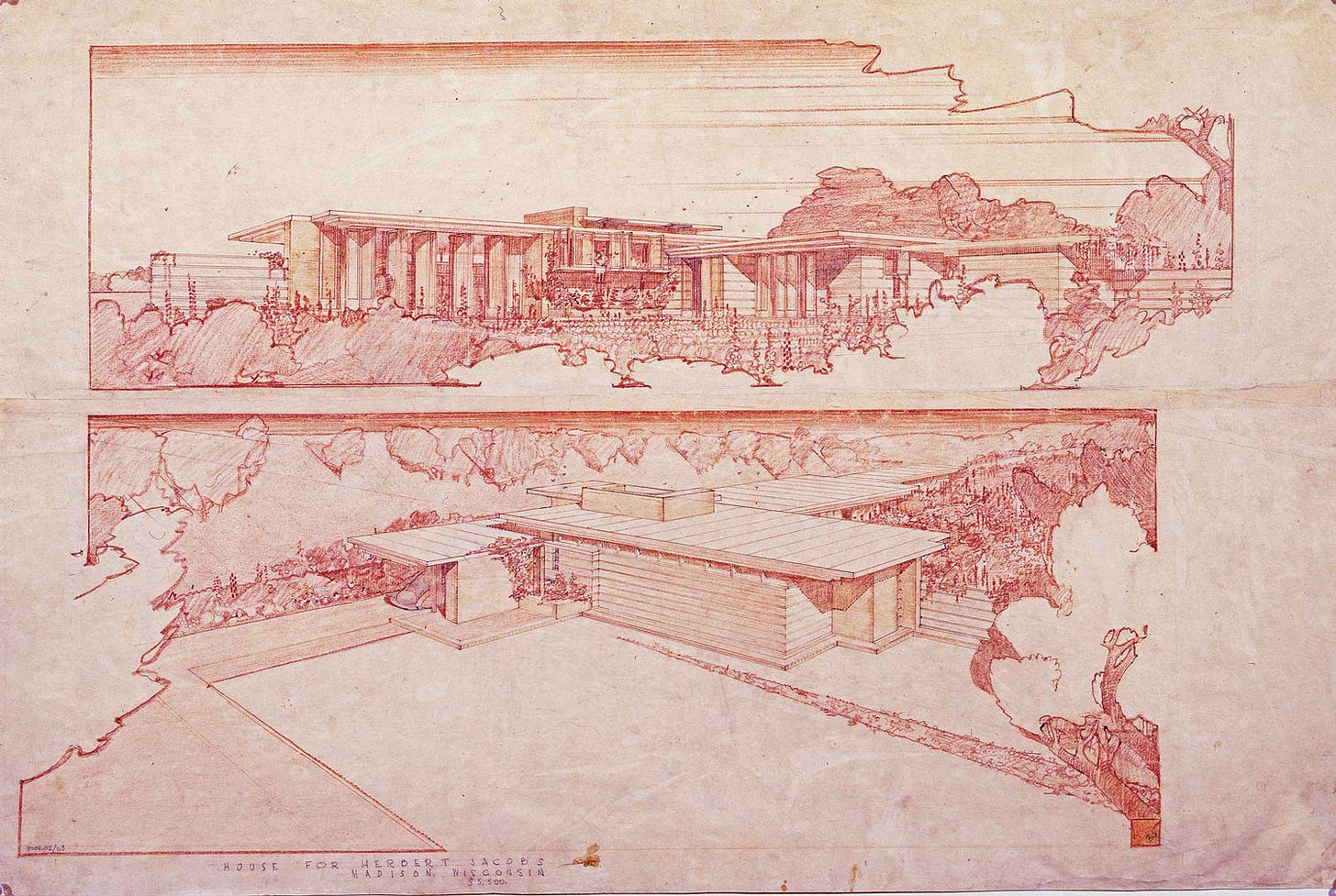

After the Second World War, Wright developed his Usonian houses, which were designed to be reasonably sized, and often prefabricated, affordable homes for average Americans. Josefin Kannin of Lindal Cedar Homes notes in a press release:

“There’s been a surge of interest in mid-century modern homes for the middle class that are affordable and aesthetically pleasing. These homes will meet that demand; they are unique, are integrated with nature, and have the feel of a much larger home. We hope the new Imagine series will be much more accessible to people who want the look of an architect-designed home but may not have the budget for a completely custom creation.”

Each of the designs is based on an existing FLW plan, and what immediately pops out is how faithful Lindal has been to the originals, and how good the originals actually were.

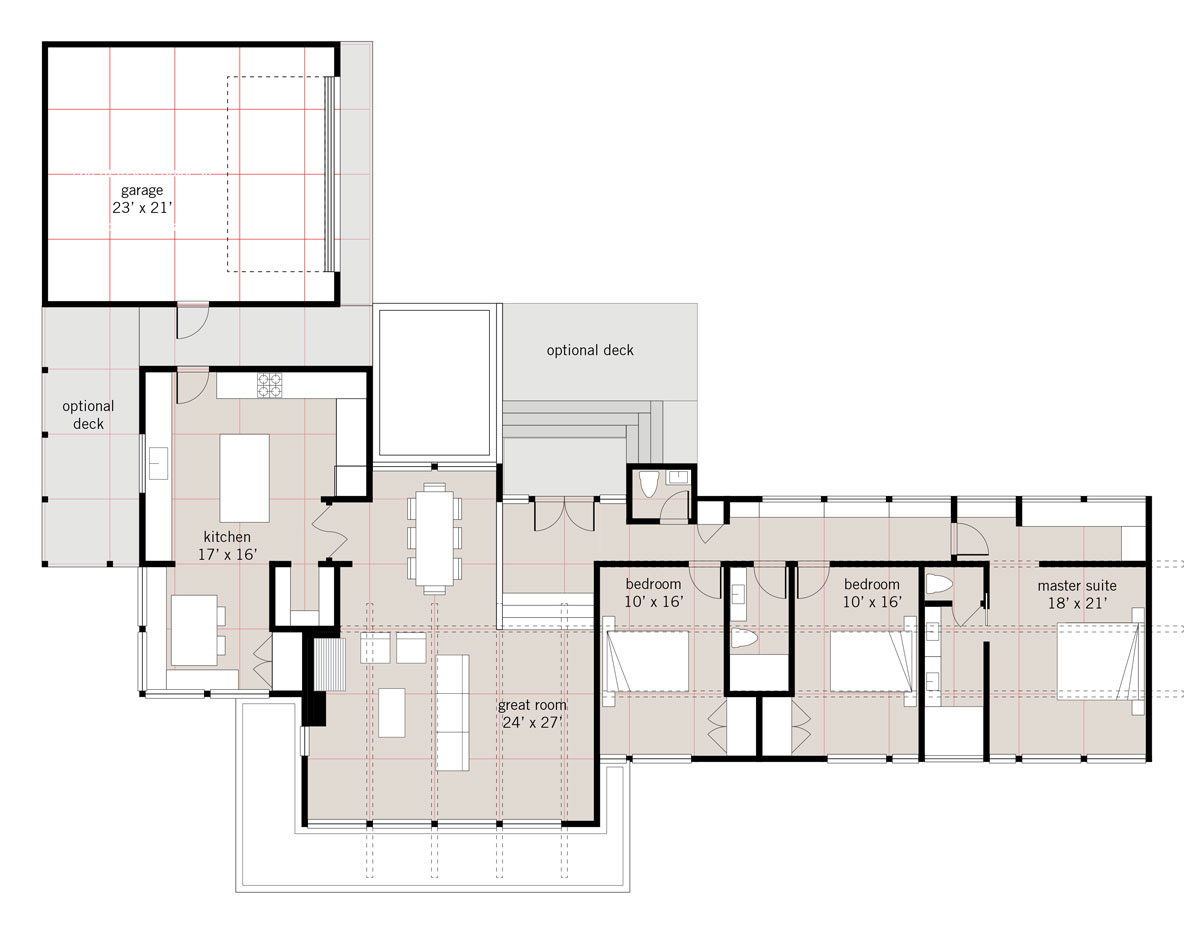

I am going to focus on one house in particular, Lindal’s 2125 square foot Laurel design; it is a “modern translation” of the Duncan House, which my wife and I have stayed in, so I can compare the original to the new design and discuss the changes that Lindal’s designers have made.

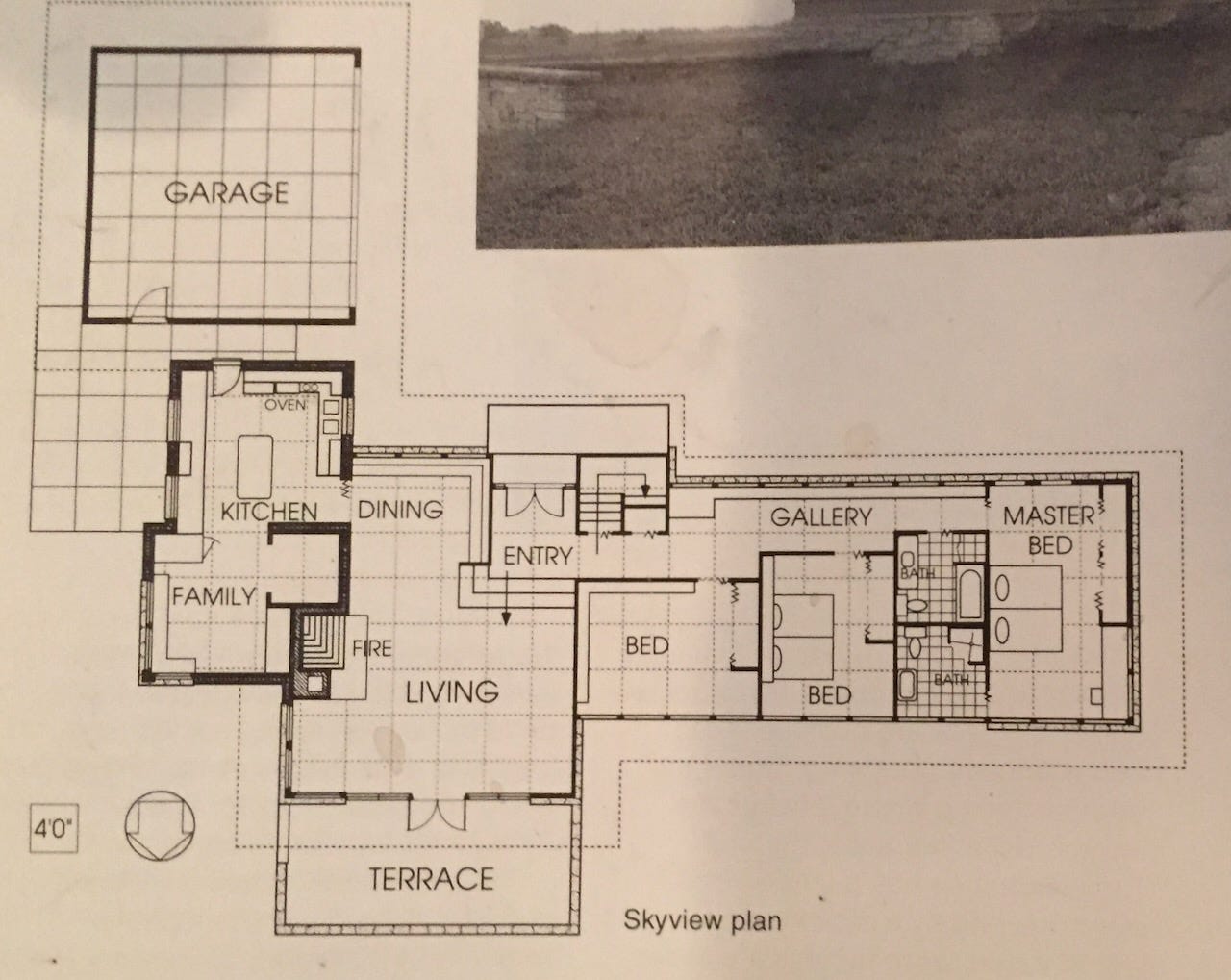

The Duncan House was one of eleven houses designed as a prefab for the Marshall Erdman Company; it is almost identical to the plan for the Jackson Skyview home shown above, but with a carport instead of a garage.

The reason so little had to change to modernize the Duncan House is that it was such a modern plan in the first place. For example, the kitchen is huge, vastly bigger than the kitchen in Fallingwater, which was designed for servants. in his book “The Future of Architecture,” Wright wrote:

“Because of modern industrial developments the kitchen no longer has a curse on it; it may become part of the living room by being related to another part of that same room set apart for dining.”

But I liked how it was still separate from the dining room. There is also an extra space labelled “family” in the Duncan House; Wright described it as:

"An extra space, which may be used for studying and reading, might become convenient between meals. In such a house the association between dining and the preparation of meals is immediate and convenient. It is private enough, too."

What has changed in the Laurel? Remarkably little. Lindal even keeps the garage detached from the house, unheard of in modern designs, but true to Wright’s principles; he considered attached garages to be dangerous.

The stair down to the furnace room has been replaced with a powder room, and the bathrooms are much more generous. The master bedroom gets a dressing area/closet, and the bedrooms are slightly larger, although still modest by modern standards. (Wright thought bedrooms were a waste of space and needn’t be much larger than the bed. He called these “small but airy.”)

Some of the flaws of the original Duncan House are carried over into the Laurel. There was and is almost no closet space at the entry, and no mudroom or vestibule at the kitchen entry. In the Duncan house, that family area was being used for storage.

They also maintain the stairs down from the main entry to the living area. This was an FLW trick to make the house feel bigger: when you come in, the ceiling in the hall is very low, with a feeling of compression; the living room is down three steps in the Duncan House (four on the Laurel plan and five on the Laurel rendering) and the ceiling is way, way up. The effect is dramatic, but I do wonder whether we should still do this in a world where we should be promoting universal design.

I imagine some will complain that these designs are not really suitable for today’s world. Passivhaus architect Elrond Burrell wrote ten years ago:

“I used to enjoy the rhythm of rafter ends projecting out around the eaves of a house. I admired timber and steel beams apparently gliding smoothly through external walls or floor to ceiling glazing. No more! I can’t help but see the thermal bridging these details create, the resultant heat loss, material degradation risks and mould risks.”

Of course, beams gliding through floor to ceiling glazing is exactly what we are seeing here in the Silverton model. Some might argue that the time has passed for this kind of thermally incorrect design.

But I have no doubt that these houses perform a lot better and leak a lot less than Wright’s ever did. I think Lindal has done a fabulous job here; they have given Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unsonian Homes a second life, reincarnated for the modern world.

A pal in Colorado designed a number of homes that they called "off site construction" rather than Prefab as the developer thought the term Prefab was off-putting to buyers.

I love the aesthetic of many of FLR designs but he was not particularly good at dealing with issues that flow from the necessity of getting rid of water/moisture. If the choice was between sensible construction and preserving the look and feel of his spaces he tended to favour the latter two. Be prepared for mold and rot if the updated versions of his designs have not systematically addressed the problems caused by that preference.