At Home With Tomorrow: A look back at prefab in 1947

A bonus from the archives, looking at the work of Carl Koch.

There has been so much news recently about how prefab could finally revolutionize housing. The Canadian government in particular has suggested that Prefabricated housing offers one solution to the supply crisis. Architects have been saying it for years; when a major prefab company went bust in 2008 I wrote a post, now deleted, about how long people have been saying prefab is the future of housing.. I found it in the Wayback Machine and republish it here:

While writing the obit for Empyrian Homes (formerly Deck Homes and Acorn Homes) I alluded to the original Acorn house, describing it briefly and noting that Acorn founder John Bemis put it together with Architect Carl Koch. I could find little information, other than references to a Life Magazine article and one reference to a book by Koch. Through the wonders of ABE I was able to find and buy a copy.

And what a remarkable story it tells, and how little things have changed in fifty years.Koch tells the story from the very beginning:

As to how it began: The idea of demountability is, of course, not new. The nomads of Asia have been at it for years, with houses of frame and hide- Yurts. Even before the second world war, there were a number of experiments with demountability or yurtdom....

At wars end I was stimulated to read about vast available amounts of surplus material. Aluminum, for instance...I began trying to bring the idea together with realities.

He began looking at stressed skins:

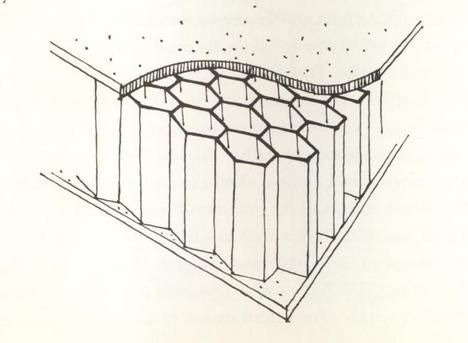

The Forest product laboratory has done a considerable amount of development work on [stressed skins.] IF you impregnate the paper honeycomb with plastic and glue it rigidly to a sheathing material you get what is known as a stressed-skin construction, which has strength and insulative ability out of all proportion to its weight and a theoretically very low cost.

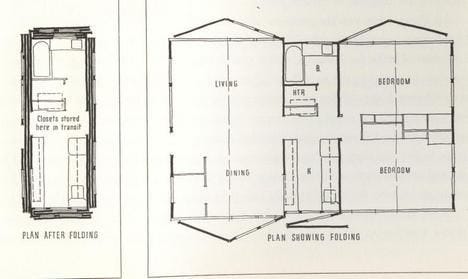

He then designed the house, using a principle reinvented many times since, in Michelle Kaufmann's Breeze house and others, where you build the core in three dimensions but the big rooms in flatpack.

Here, at any rate, was an estimable means of enclosing space- but how much space, of what shape, and how divided up? Here there was a handy necessity: if the house were to be portable by truck, no section of it should exceed a width of eight feet. The question then was what part of the those might be designed, sawed, folded or otherwise compressed into eight foot widths and what might not?

It seemed reasonable that one such section, 8 by 24 feet, should comprise the core of the house: the kitchen, and bathroom, plumbing heating and the like. The reasons were several; For one thing, eight feet is a good width for a kitchen. For a second....the stringing of pipes to widely separated areas, and the innumerable, individual tasteful ways of hitching them up have raised plumbing from a craft to a fine, expensive art. For a third reason, to anticipate a point, it's hard to fold a bathtub.

He then went off in search of surplus materials and thought the airplane companies might want to build the house- they needed something to do. They said SURE!

If the government would put up a few million dollars to get the thing started for them. After all, that is how they made planes- cost-plus and all that.

He went to the government- interest and promises but nothing practical or immediate.

He went to the aluminum companies:

They weren't just sure that they wanted to manufacture whole houses. But the research director of one of the largest companies was pinning his bright future hopes for housing on the making of doorknobs.

Finally he met John Bemis, an engineer and son of a pioneer builder, who decided that if no one else was going to build the house, then by gollies, he would.

They were not fond of the name Acorn, (Folding Homes and "Resin-dences" were considered) but stuck with it. That is when the trouble started. For it was not a conventional house.

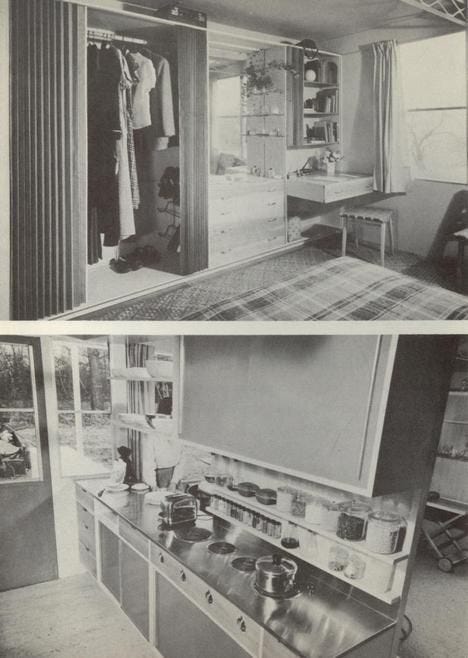

Nothing but the best: Photo credit Ezra Stoller

To understand our difficulties in this regard, [finding a site] you need only reflect on the matter of building codes, and on how vastly different the Acorn was from what people were used to. In appearance, to be sure, it was rather unobtrusive and demure, but with respect to structure, particularly in methods of plumbing, framing, and foundation, it was probably in violation, on fifteen or more counts, of the building codes of every town in New England. That is was superior on all counts to most houses constructed by code was, as we would discover, nothing to the point.

I wish I could continue typing the next three pages of their fights with building inspectors, it is familiar to any innovative architect alive. The discussion about foundations (the house sits on piles) is particularly delicious:

"But look at that foundation! It wouldn't support a meringue". Because of the Acorn's light weight, we would explain, it wasn't a matter of holding it up as much as bolting it down.

To me, lightness and tautness and resiliency are joyful, like that of a boat. But to generations of good citizens, lightness is equated with weakness, destructibility.

But if the codes were a problem, the politicians were worse. at one board of appeal, a member noted that while the house was not his cup of tea, the engineering data were convincing and he would approve the application.

The second member spoke up. " I," he said, "was elected to stop the building of cracker boxes in the town of Belmont."

They moved to Concord, and set the house up with coverage by Life Magazine and photography by Ezra Stoller, the best architectural photographer in the East. They got lots of favourable publicity from it and Architectural Record, and then, in words that so many architects and pioneers of prefab could write themselves:

We received several thousands of letters from legitimate, interested buyers, as well as many offers of land to put up more samples on. And a few messages, under important seeming letterheads, saying "If you can deliver four thousand units in the next three months, maybe we can talk business."

Over the next year or so, we followed down as many leads as we could. But we were beset by the same problem we had begun with- the chicken and egg: without a demonstrated product, no capital, no plant. Without capital and plant, no product to demonstrate......a trip to the moon was easier.

And as we know from the history of Acorn and Empyrian, Bemis and Koch moved on to building prefabricated components that any building inspector and politician could look at and understand. But it will come back; Koch concluded with tongue in cheek:

Any day now, we expect to hear that the government has hit upon the idea of prefabricated housing, and is considering a series of tests to evaluate it. Might invite a number of firms to design and enter houses.....

Since I wrote that original post, I have returned to Carl Koch and that original Acorn house in discussions of Boxabl:

Boxabl Launches $50K Foldable House

Also I mentioned it whan discussing a new design from Broad in China, which has also been deleted but is in the Internet archives. I will reconstruct it next. And a hat tip to Gary Fleisher, whose Modular Home Coach site was the source of that first link back in 2008. He will never be deleted.

Affordable Vet housing approved by the VA

What is , if there is , the difference between prefab and a structure that would be manufactured at a local facility and structural elements ie walls etc delivered to the building site for assembly.

My personal feeling is the current prefab infrastructure is energy wasteful and a throwback to the Sears catalogue.

Given modern technology, wouldn’t a localized facility using CAM technology be more efficient?

Where is the disjoint(s) in the building industry?