Is good old plywood the ultimate engineered mass timber?

This guide from the early sixties shows how you can do so much with so little.

It’s summer, it’s hot, the Olympics are on, and I have found it hard to think and write. Last week was the first since I started this Substack that I just couldn’t crank out three posts; I apologize to everyone who was staring at their inbox in anticipation. Also, we are at our cabin in the woods, and it’s hard to look at a computer when you can look at a lake.

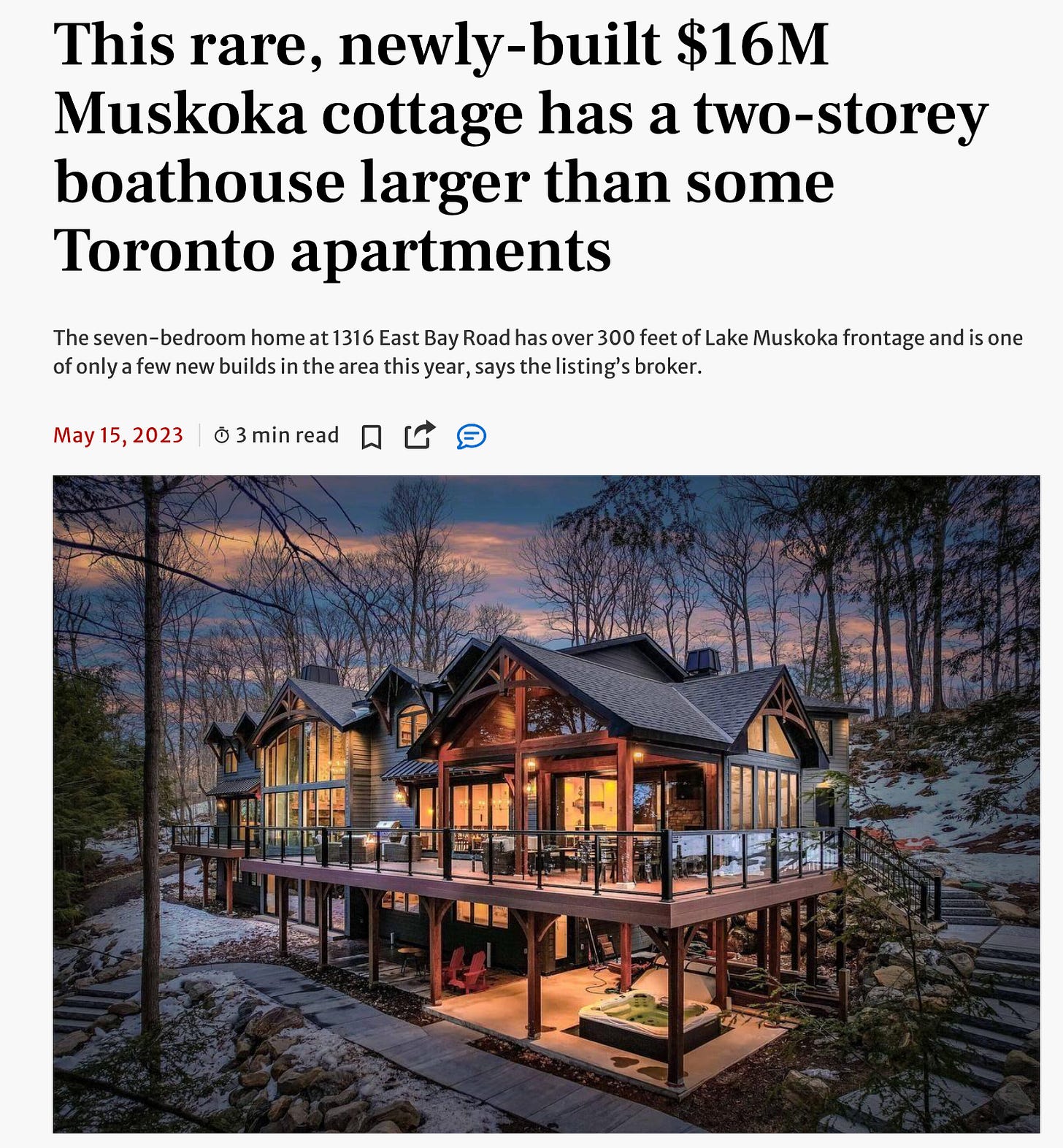

I do find time to look at the real estate ads and worry about the proliferation of vast, expensive second homes in Muskoka, the high-end cottage country in Ontario. This one isn’t the largest, the glassiest, or the grossest, but I liked the Toronto Star headline describing how the boathouse alone was bigger than many Toronto apartments.

It got me thinking, as I do about everything, about sufficiency, about what is enough. How much do you really need? Of course, the immediate answer is that nobody needs a second home at all, but I bought a tiny geodesic dome years ago before I learned that. Most of the cottages built on our tiny lake were modest, built by Second World War veterans, and many were handed down to their children who have made modest additions.

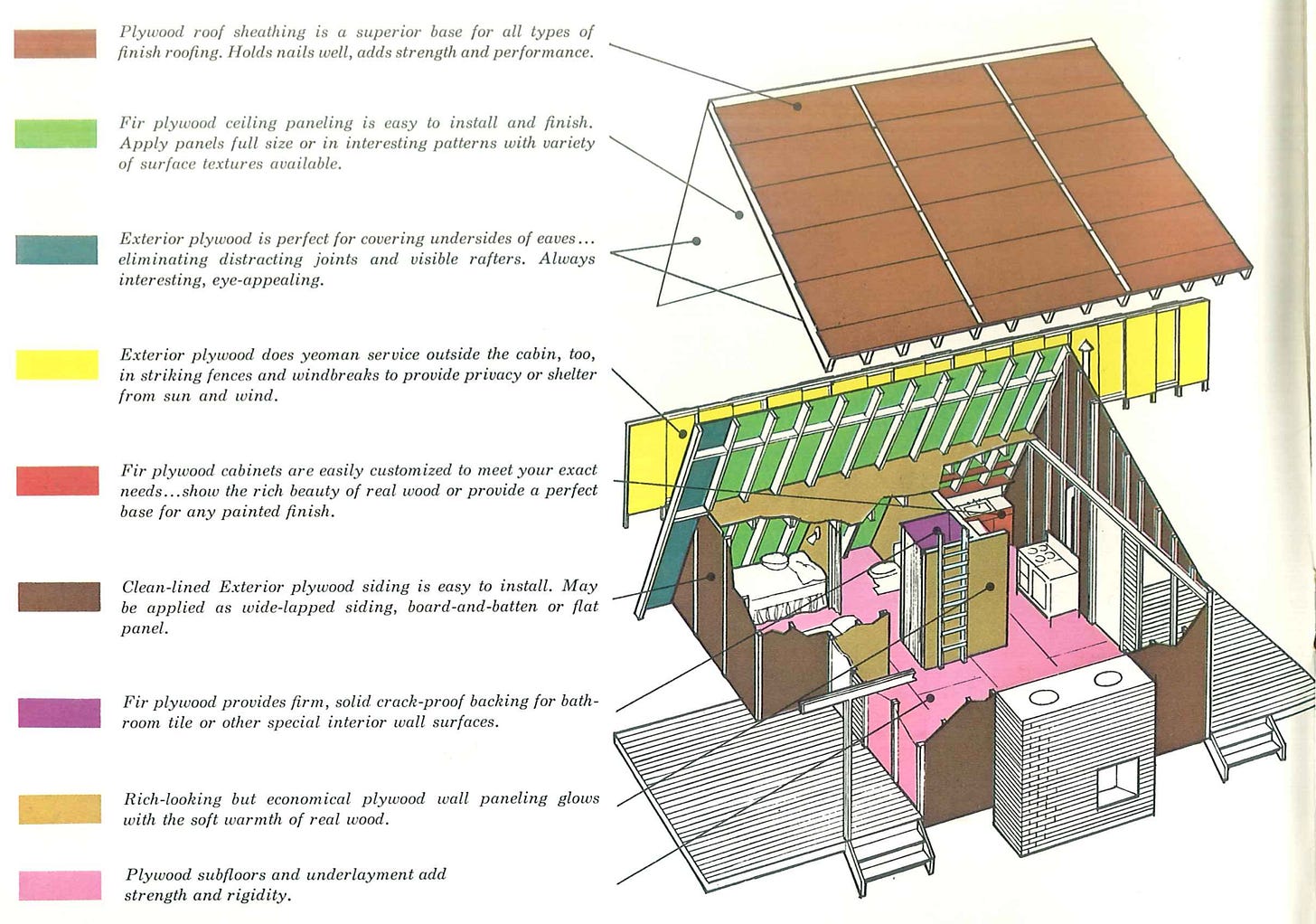

Families across North America did the same thing, and they did not look like the massive timber frame and glass house. They might look more like some of the designs from the Douglas Fir Plywood Association (DFPA), promoting their product, “big 32-square-foot panels of fir plywood enable you to “hurry up and rest” if you do the building yourself… save untold hours of costly on-site construction if you hire to get the building done.”

There are so many wonderful wood technology acronyms these days, from CLT to NLT to DLT to LVL, (see my post explaining the difference between them all) but good old plywood is the original engineered wood, so thin and so strong. Perhaps it needs a sexier name; mill decking was around for 150 years in every factory and warehouse and is now NLT or nail-laminated timber. Maybe plywood should be CLV for Cross-Laminated Veneer; it is thin, strong, and modular and put to great use in these minimalist designs.

Besides sufficiency, these designs follow another important principle that I often discuss: The DFPA says, “One word of caution before you start your second home project: Keep it simple!” Combine radical sufficiency with radical simplicity, and you have a design where all the material can probably fit in the back of a pickup truck (if pickup trucks could still carry a 4x8 sheet of plywood)

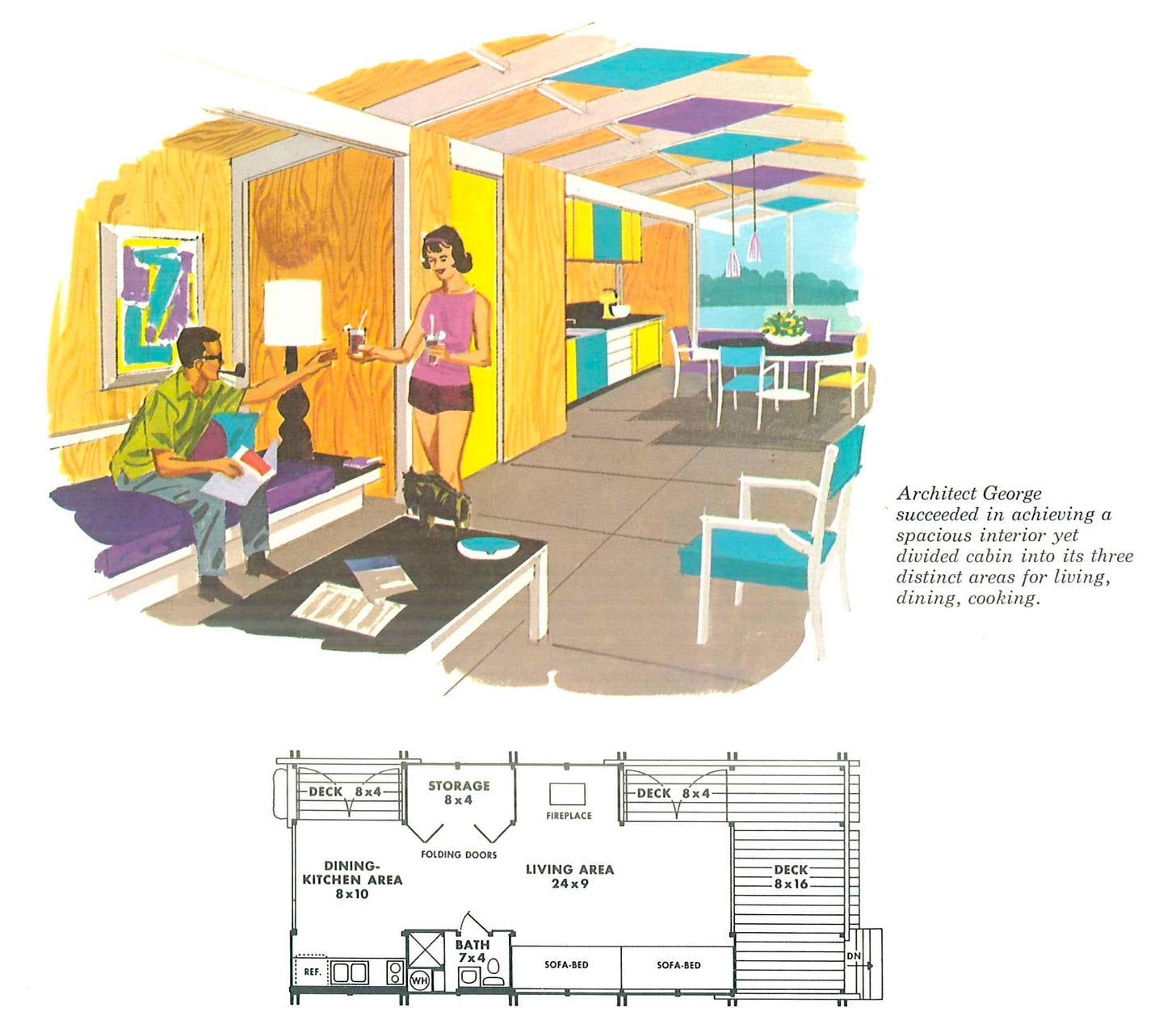

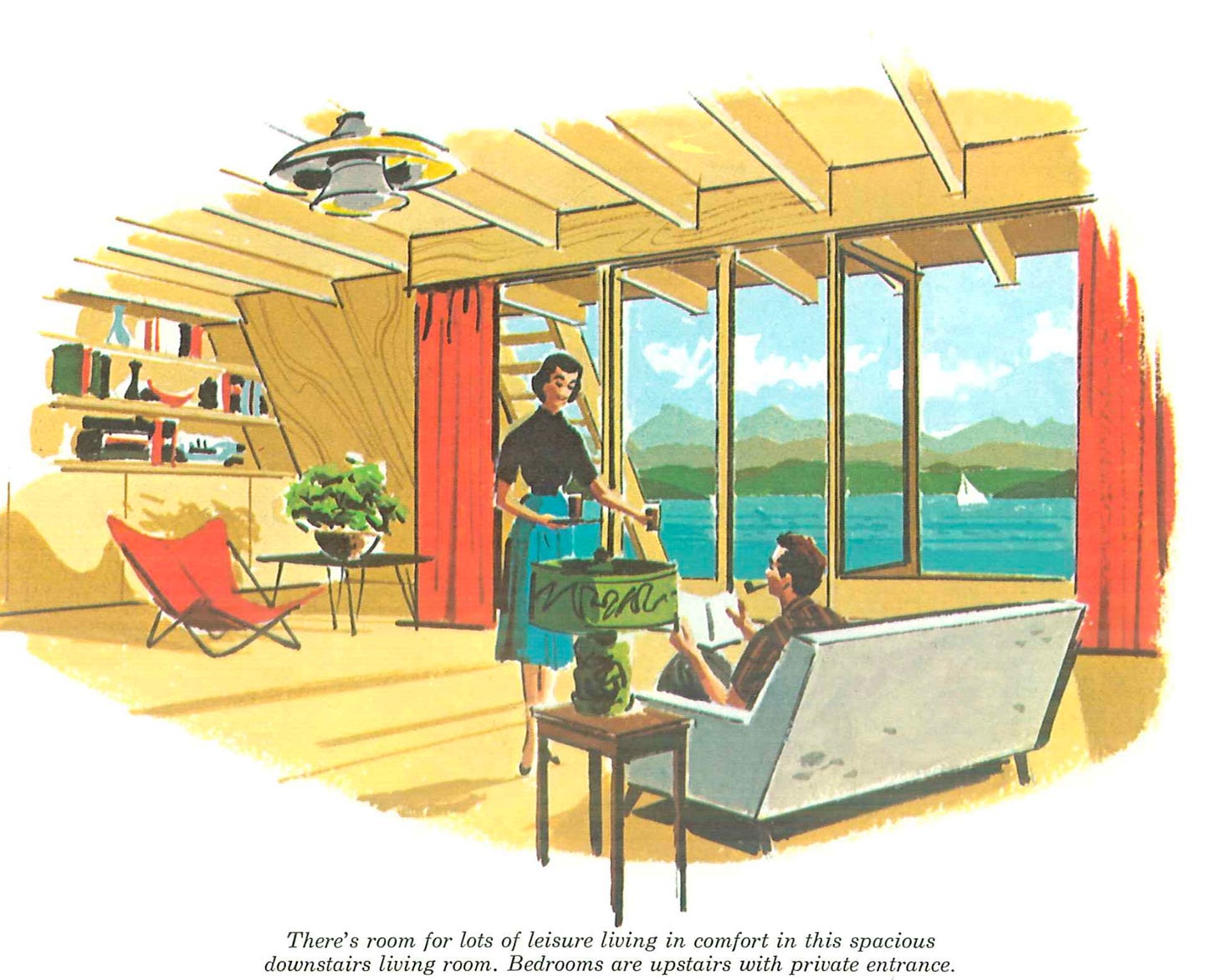

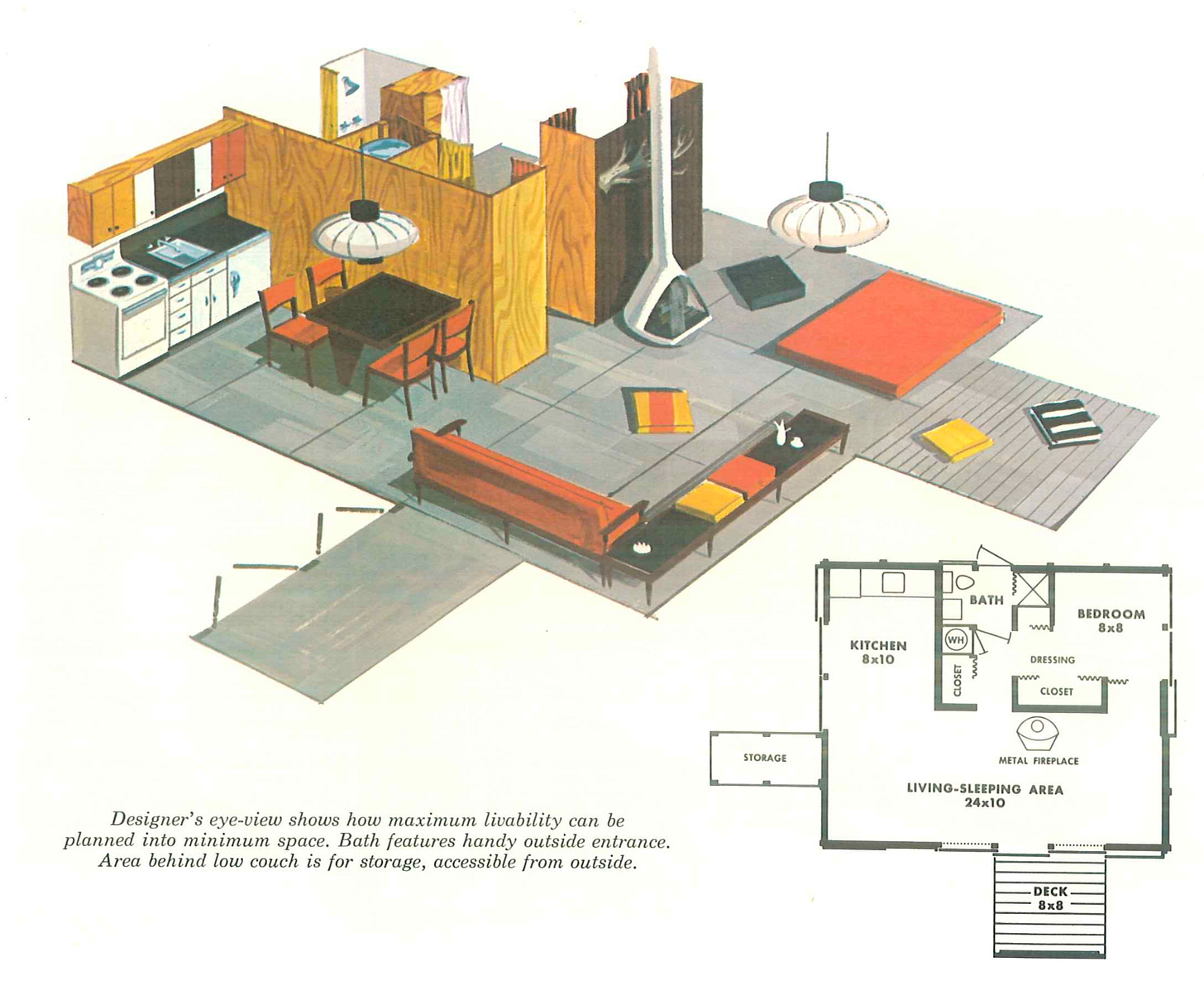

Some of the plans were so modest that they didn’t even have bedrooms; you slept in the living room. Perhaps Architect George could have closed off that last sofa bed on the right with a moveable partition. It’s really a plywood tent; "Exterior fir plywood serves as both inner and outer wall- presenting a durable paintable surface to the elements on one side; a warm friendly atmosphere inside.”

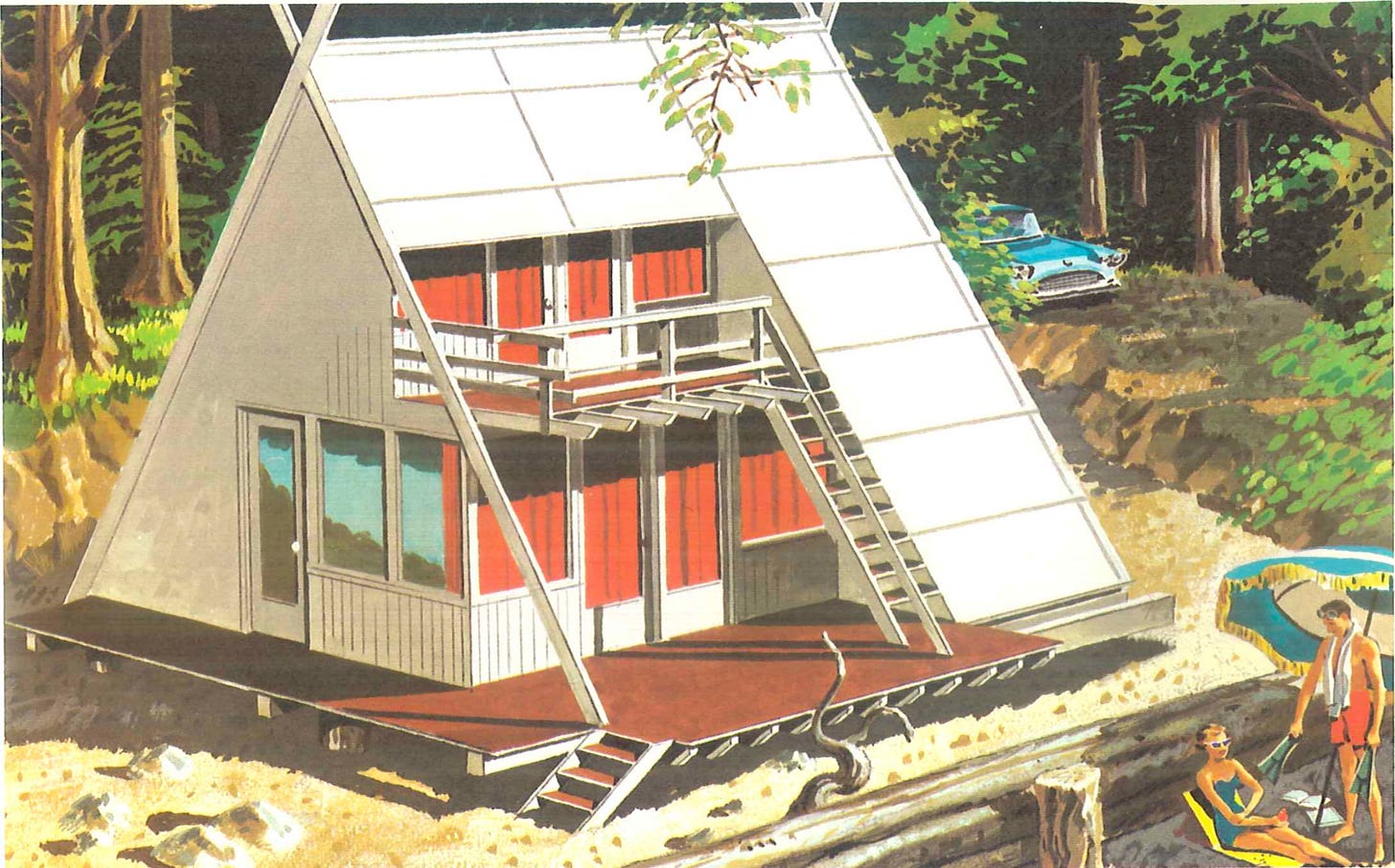

Among the simplest designs are A-frames, which can be among the cheapest to build; there are almost all roof, and nothing is cheaper than shingles. They often fail for design efficiency, since triangles enclose the least amount of area and the second floors are very tight. But as Chad Randl noted in the introduction to his book A-Frame:

"A" was the architectural letterform of leisure building in postwar America. Eager to stake out mountain and lakeside retreats, an entire generation of high-end homebuilders and weekend handymen found the A-frame an easy and affordable home to construct; its steeply sloping triangular roof distinctive and easy to maintain (almost no exterior walls to paint!). Fueled by A-frame plans and kits, the style became something of a national craze, with tens of thousands of houses built.”

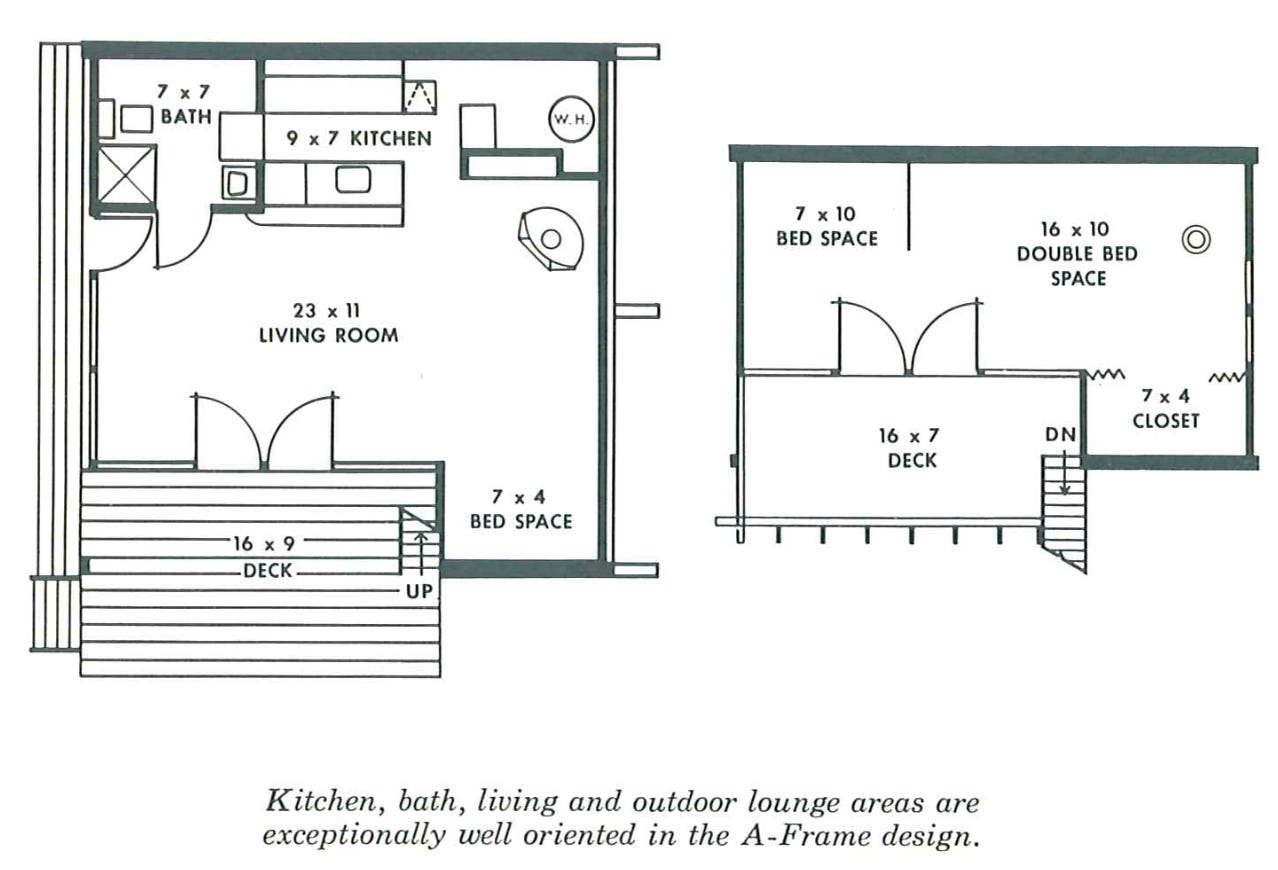

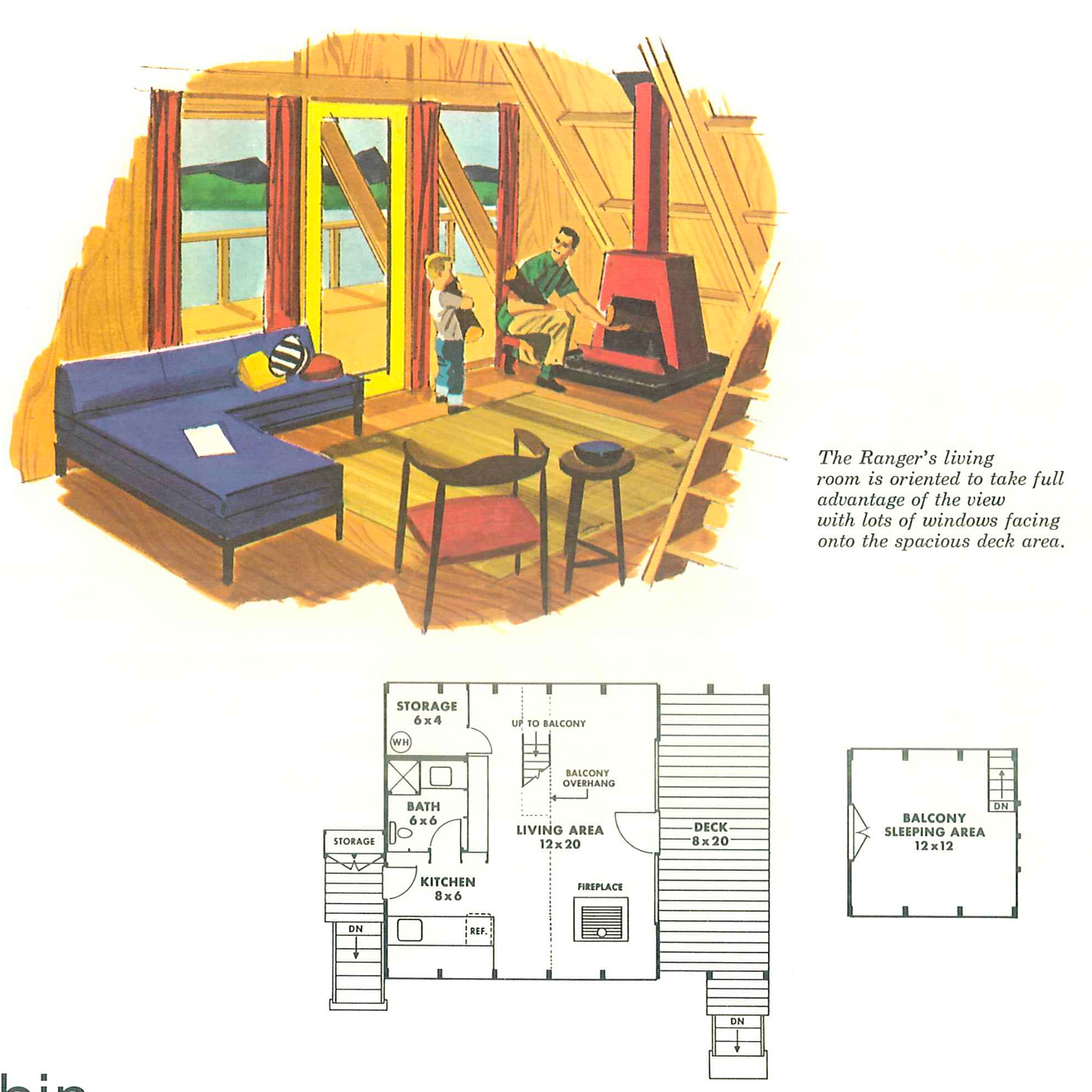

This plan works because the stairs are outside, which can be a bit of a pain if you have to go to the bathroom at night and it’s raining. It also mucks up the simplicity of a-frame design with that deck on top; there is some weird framing going on to hold it up.

The ground floor is generous, though, as they often are on A-frames.

But even the greatest architect of the A-frame, the late Andrew Geller, mucked up the purity of the frame to get a little extra room on the upper level, as seen with that box on the left in the Elizabeth Reese House in Sagaponack, New York. Alastair Gordon describes Geller's thinking in his obit for Geller:

“His theory was that the sloping walls of the A-frame would be “storm proof”– less resistant to hurricane winds. That was the idea anyway; it also happened to be the cheapest way to build a roof. Complaints from the local building department were countered with the explanation that the unusual shape of the house was derived from local potato barns.”

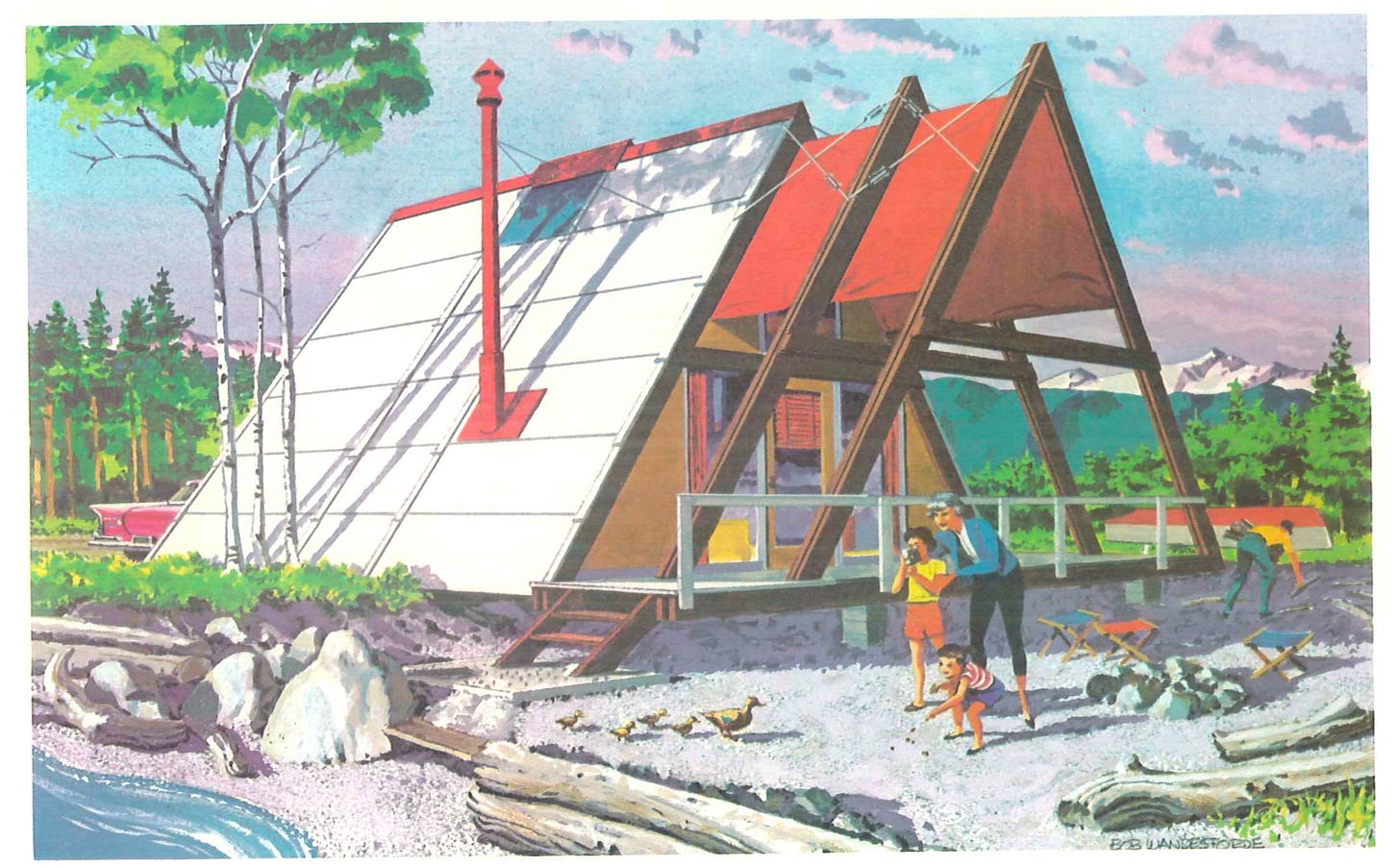

The other DFPA A-frame has two extra frames added to the exterior “to relieve the spartan A-frame lines” but also to provide “a spacious sundeck to for a shelter from the sun in both summer and winter.”

But it also has an awkward plan, with just a 12x12 sleeping area over the kitchen and bath. The closer I look, the more I wonder if my love for the A-frame is misguided.

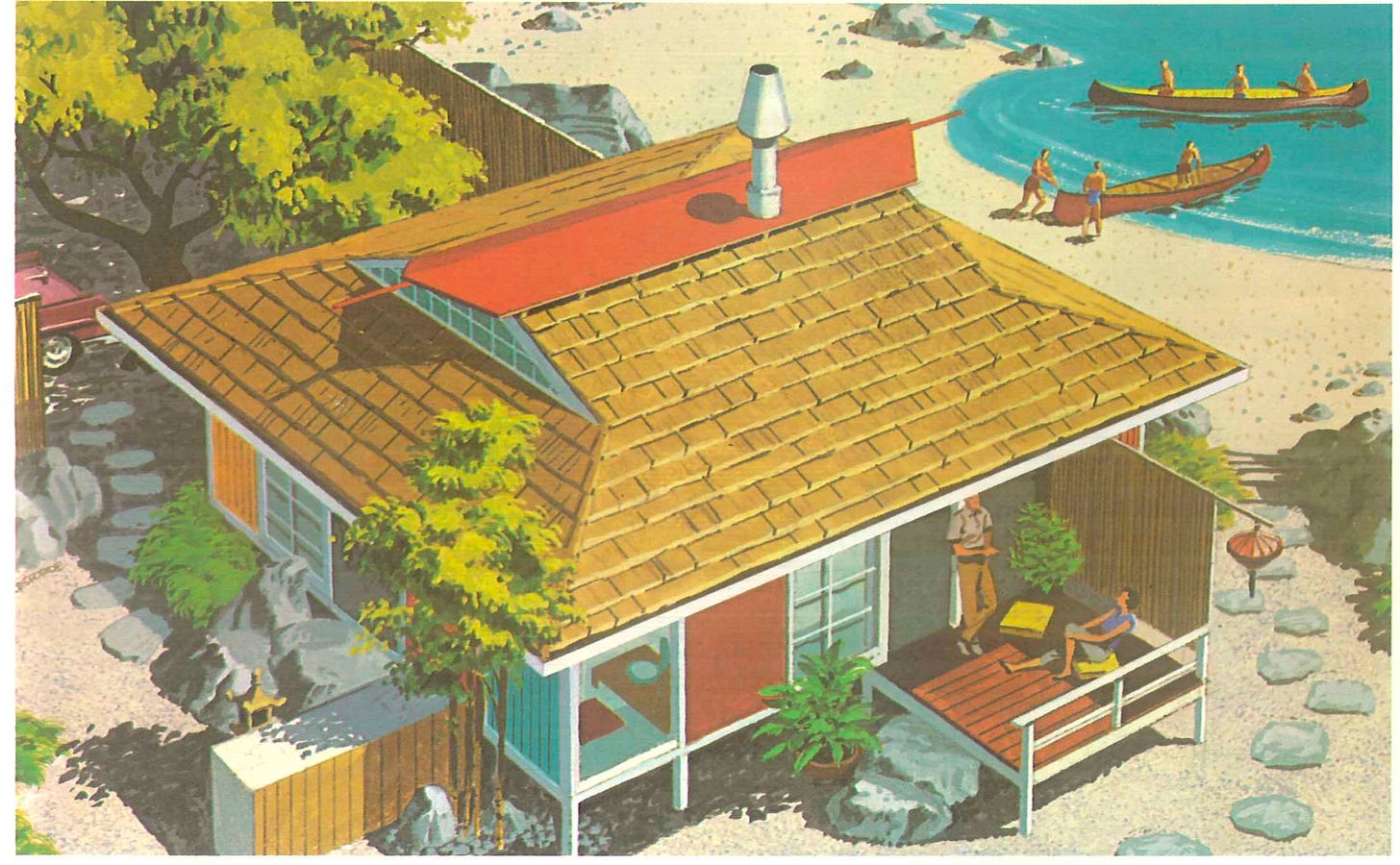

Look at what architect Laurence Higgins fits into 480 square feet: a Japanese-inspired “tea house.” Just don’t do that roof with the upper triangular windows; I did that on my cabin, and the framing gets complex. My builder Brad disparagingly called it a “Pizza Hut roof,” and I have never got that image out of my head and have wanted to change it ever since.

But look at that clever plan, so much in such a small area.

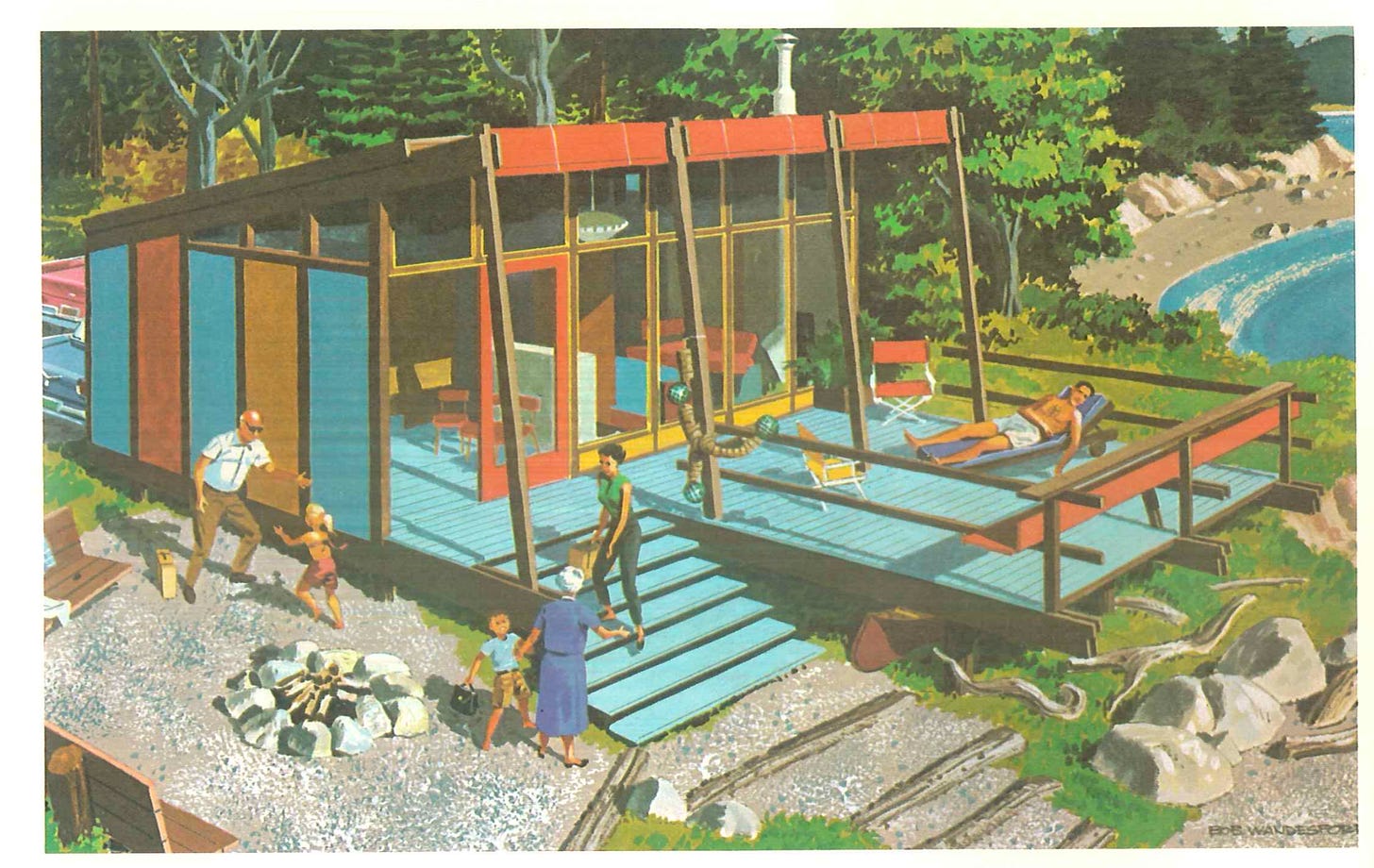

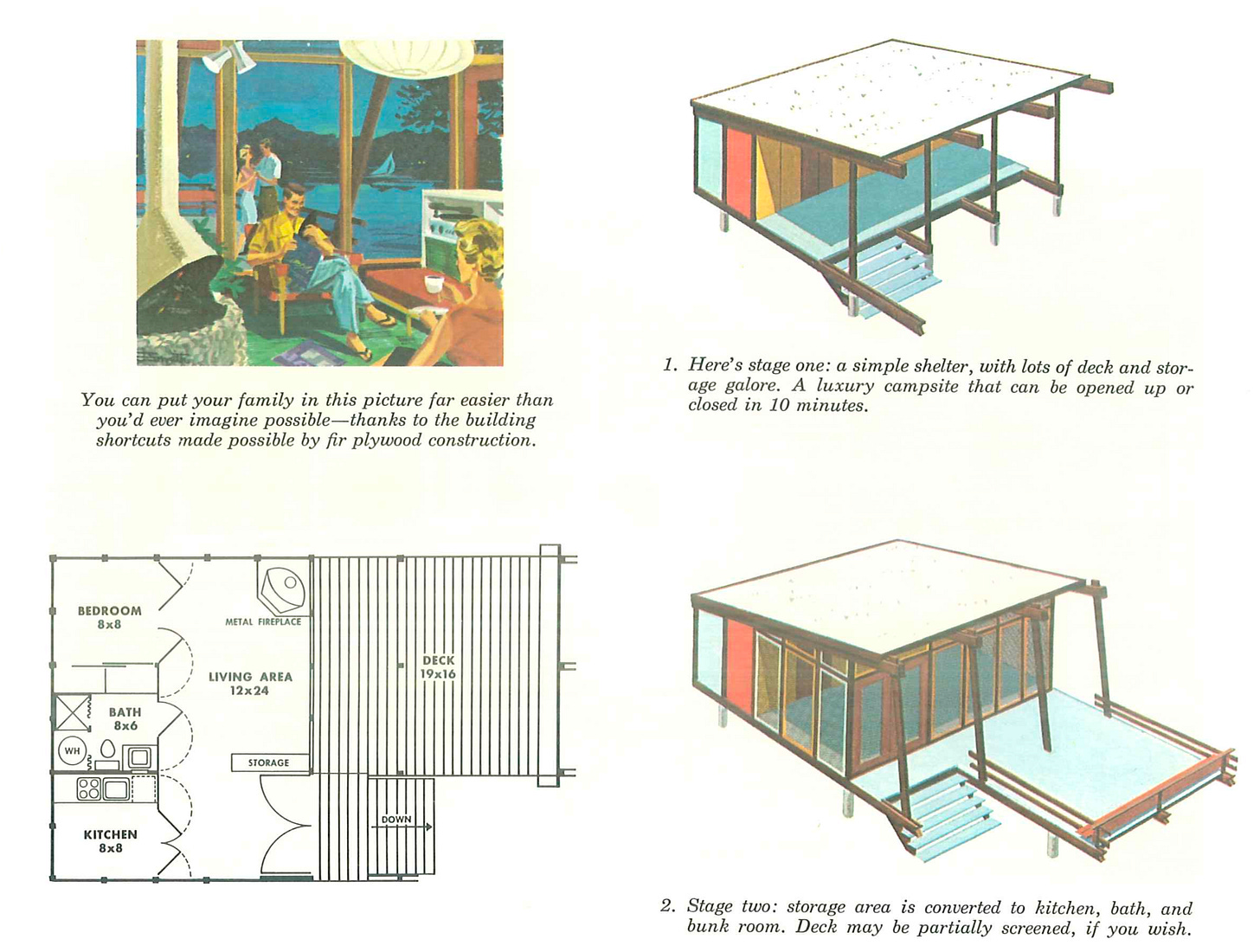

Then there is the “3 Stage Beach Cabin” where you start with $900 worth of materials and build a storage shed on the beach, which then gets expanded in stages until it is big enough to invite the grandparents.

Stage two is pretty silly: just screening in the living area. Just close it in and be done with it. But “big, light, strong fir plywood panels make the work simple.”

Unfortunately, one probably can’t build any of these anymore; here in Ontario, if you want a building permit, you have to build to the building to code with insulation and double-glazed windows. I got away without doing any of this because there is an exception for sites without access or services like ours. And then there are often minimum floor area requirements to keep out the riff-raff- municipalities are not interested in sufficiency, they want real estate taxes.

And really, who is going to go to a summer cottage without a “soundproof home theatre with a stadium seating of 10 chairs” like this one in the Toronto Star cottage?

There is no question that people’s expectations have changed, but perhaps there is a happy medium.

I have long been a fan of plywood, whether in Eames chairs or Mosquito airplanes. After visiting a wonderful show on plywood at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2017 I wrote this post for Treehugger that has not yet been deleted: It's Time for a Plywood Design Renaissance.

And I just wrote last week about the wonders that Facit Technologies is doing with plywood boxes. It is still the miracle material.

I love plywood too but OSB is now half the price and has taken over. Personally I'm not a fan of building with stiffened oatmeal, however.

I would have thought that LVL had the edge on traditional plywood. From what I have seen the utilisation of the raw material is higher with less wastage. It can also be used for more structural purposes than plywood. The only place plywood seems to win is in applications that need very large thin panels.

Would you agree Lloyd?