Based on Le Corbusier’s Manual of the Dwelling, this is a series where we develop a manual for understanding the homes we have today and what they must become – resilient in the face of change, supportive of our health and well-being. Efficient but, more importantly, sufficient – just what we need to be happy, healthy, and comfortable.

Yesterday I reposted some older posts I wrote about baby boomers and the housing market. Many of those boomers live in houses with stairs, which many people think is a problem. In fact, those stairs may well help keep them healthy and in their houses a few years longer.

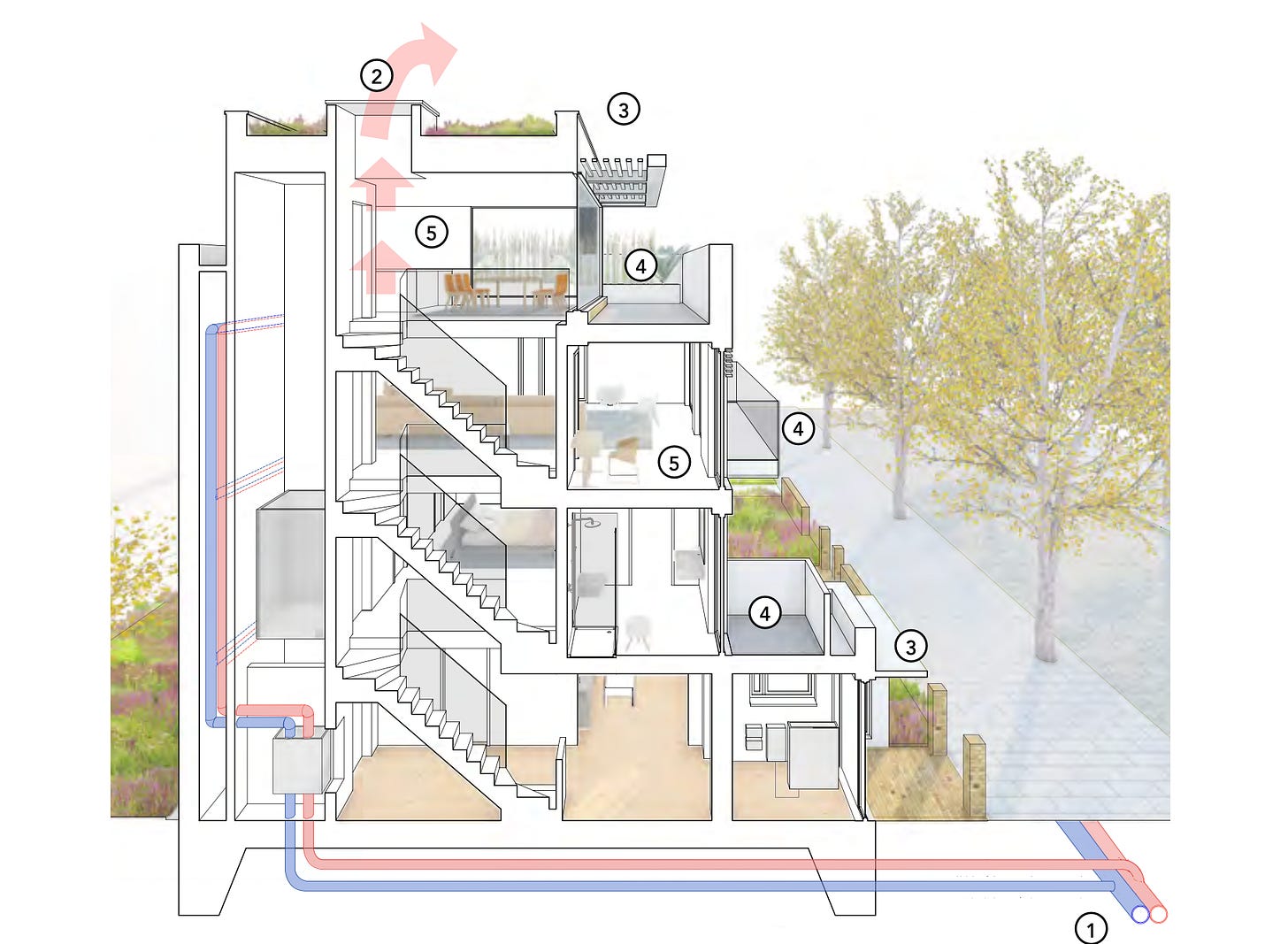

A few years ago, I wrote a post about a British report, Futurology: the new home in 2050 and the comments were all “This is housing for the future? So many stairs! What about when you get older?” In fact, that house of the future has a lift, the grey box behind the stairs, so it is accessible. But every time I showed a house with stairs, people would complain. You can imagine the comments when I admired the stairs in Montreal.

Contrast that with the North American dream of a retirement home, which is almost always in a sprawling single storey with a garage big enough to have a wheelchair-capable van, in a community with a walkscore of zero. Discussing this house, I noted that it wasn’t designed to age in place in; but is in fact probably exactly the opposite, a house that might in fact age you in place.

A Japanese study1 found exactly that; it followed 6,000 people who moved from houses with stairs into single-storey dwellings lost the ability to perform “instrumental activites of daily living” (IADL) significantly sooner.

“The presence of stairs in the home was associated with prevention of IADL decline over a 3-year period in older women without disabilities. Although a barrier-free house is recommended for older people, our findings indicate that a home with stairs may maintain the capability to perform IADL among older adults without disabilities.”

There is even a syndrome called “bungalow leg.” Dr. Carolyn Greig told the Daily Mail: ‘There is a deconditioning element associated with moving into a bungalow and a definite concern that moving may hasten decline. Climbing stairs is a very good way of maintaining or improving muscle strength and muscle power. If there is a significant number of stairs it also provides an aerobic challenge as well.”

Stairs are great exercise, as the numbers show on these stairs in Seattle’s Terry Thomas buiding. In his book, The Miracle Pill, Guardian columnist Peter Walker writes:

"It goes without saying that habitual stair use brings health benefits, and equally inevitably these have been proved via long-term mass studies. A 2019 paper using some of the decades of data from the Harvard Alumni Health Study, first developed by Ralph Paffenbarger, found that even after factoring out all other activity, habitual stair climbers (those who ascended thirty-five or more flights a week) had just 85 percent of the mortality risk over the course of the study than those whose weekly average was ten or fewer."

Duke University noted the benefits of taking the stairs:

There is a significantly lower risk of mortality when climbing more than 55 flights per week

Stair climbing requires about 8 - 11kcal of energy per minute, which is high compared to other moderate level physical activities.

Active stair climbers are more fit and have a higher aerobic capacity

Even two flights of stairs climbed per day can lead to 6 lbs of weight loss over one year

There is a strong association between stair climbing and bone density in post-menopausal women

Climbing stairs can improve the amount of "good cholesterol" in the blood

Stair climbing increases leg power and may be an important priority in reducing the risk of injury from falls in the elderly

Stair climbing can help you achieve and maintain a healthy body weight

Stair climbing can help you build and maintain healthy bones, muscles and joints.

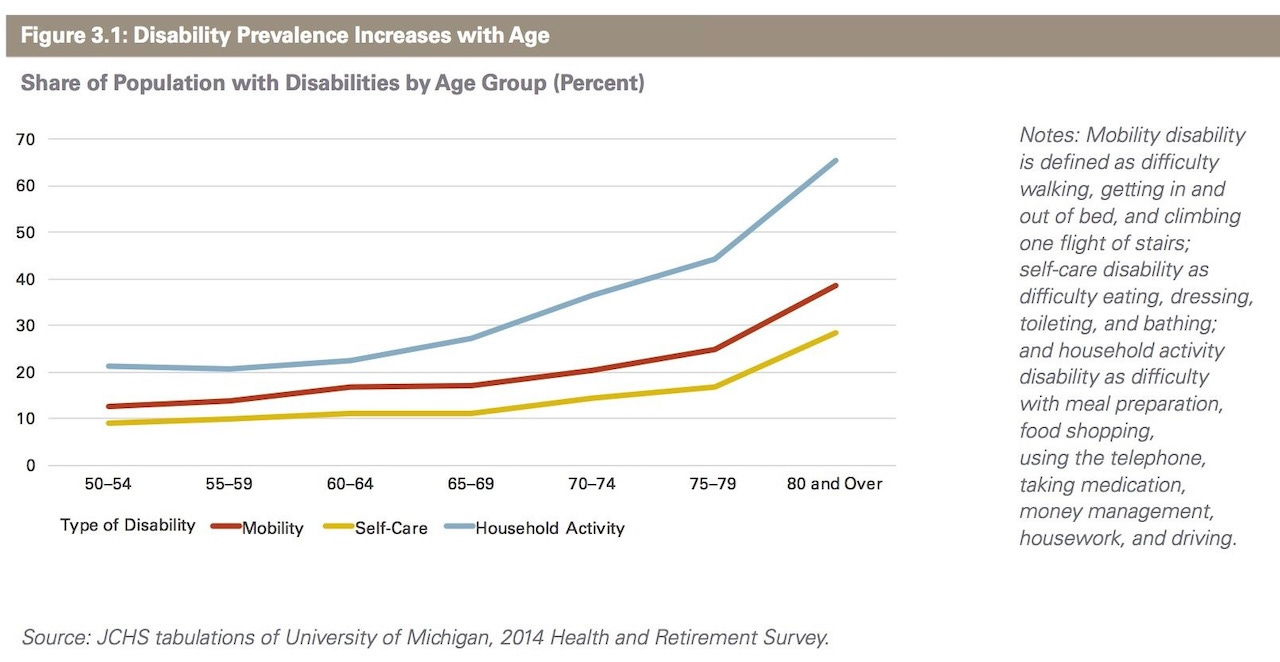

The other factor that the bungalow crowd ignores is that one tends to lose the ability to climb stairs (mobility disability on this table) at a significantly older age than losing the ability to drive (household activity.) So you are much better off to live in a walkable community with a few stairs than you are in a bungalow in the ‘burbs.

At some point, the stairs can become an issue. My mother-in-law lived in a 60s sidesplit with the kitchen on one level and the bed and bath up half a level, a powder room at the entry down half a level. Some days near the end of her time there she had do decide which was more important- access to the kitchen or the bathroom, because getting between them was so hard. That’s when she decided it was time for a retirement home. But my wife Kelly is certain that the stairs kept her going a lot longer than she might otherwise have; it was the only exercise she got.

There are ways to deal with this through good design; we have shown many plans with a “flex room” and a full bathroom on the ground floor of two-storey houses that can go from being a home office or den to being a bedroom, as shown in the Go Logic Home shown here. That seems to be a smart compromise.

We need smart compromises, because there are obviously people with disabilities who need universal design and full accessibility. But we shouldn’t lose the stairs because people also need the exercise.

I renovated our house so that we could stay in it forever, downsizing to where we live in the lower level and ground floor, with stairs in between. Kelly and I are up and down those stairs many times a day, if only to let the dog out.

I am not particularly worried about not being able to climb them, but there is a nice void space in front of that bookcase where I can slip in a lift if we have to. Every house should be designed to be adaptable and flexible in case circumstances change; it is as simple as designing stacked closets so that a lift can be installed if required; that costs nothing now and can make a great difference later. But the data show that the number of people who will need it is very small.

With our renovation, our house went from one dwelling to two, from two people to six and three dogs. Shortly after the reno I was interviewed by Alex Bozikovic, architecture critic for the Globe and Mail, and described why:

Alter, who is a writer on design and sustainability and an adjunct professor at Ryerson University, argues passionately that being located in a walkable neighbourhood, served by transit and connected to neighbours, is what matters as one ages.

"Older people, when they move into single-family houses in subdivisions, they're setting themselves up for failure," he says. "It's a hell of a lot likelier that they'll lose their keys before they lose their ability to walk up the stairs.”

"This is one solution: this re-intensification of our neighbourhoods."

I used to see my elderly neighbour Gonsalves dragging the recycling bin up his front stairs and would offer to help; he always turned me down, telling me his family in Spain lived in a town with hundreds of steps, and they all lived to be a hundred. He made it well into his nineties, taking what Peter Walker called “the miracle pill”- walking everywhere and taking the stairs. We all should.

Excellent article. My mantra for the past few years has been “just keep moving”. If I am moving I am pretty sure I am not dead. It seems to me that somewhere along the line we developed the notion that we should respond to aging by taking it easy so that we don’t hurt ourselves. My experience is that the exact opposite is true. As I have aged I find that I need to push myself physically, and mentally, harder. Neglecting to do so accelerates my decline at an astonishing rate. So, I push myself constantly to lift more, stretch more and walk more and to actively seek paths in my day to day activities that force me to climb. The results when I slack off are terrifying. The results when I push myself are inspiring. While being careless about it and not accounting for the reality that time breaks us all down is a mistake, the evidence is clear that we can slow our decline dramatically by pushing ourselves physically and mentally. I seem to recall reading somewhere that there was a remarkably high correlation between active life expectancy and the degree of elevation change that people covered over the course of their days across most or all of the so called blue zones around the world. While I am very careful when connecting correlation to causation in general, I say bring on the stairs.

I don't understand how you resolve this line: "At some point, the stairs can become an issue."

... with, "We need smart compromises, because there are obviously people with disabilities who need universal design and full accessibility. But we shouldn’t lose the stairs because people also need the exercise."

It's not about stairs, it's about remaining active, PERIOD. Many more people fall down stairs and become seriously injured when they're elderly than they do maintaining health simply by traversing stairs multiple times a day. I fail to understand how you're trying to thread the needle by stating BOTH can be true and that people should put stairs into their homes strictly for the purported health benefits.

The Japanese study? It's an attribution study, and doesn't necessarily reflect anything any more than two completely disparate metrics correlating. A person gets just as good of health benefits walking on loose sand at the beach, all without having to rip out a corner of one's home to install stairs or a lift.