In praise of slow cars

Slowing down is a great way to deal with the climate crisis. It also saves lives.

Doug Ford, the Premier of the Province of Ontario where I live, is trying to kill us. At the same time as he is closing hospitals, he is making beer and wine available at corner stores (we used to have to get wine from the government-run liquor stores and beer from special beer stores). And now, he has increased the speed limits on some highways by 10 km/hr. His trained seals, who repeat everything they are told to tweet, say, “Under the leadership of “Fordnation,” our government continues to stand up for drivers.”

10 km/hr isn’t much (6.2 MPH), and everyone drives 20 over the limit anyway, but it speaks volumes. The speed limits were dropped to 100 in 1976 to save energy, following the American reduction to 55 MPH, but it also saved lives; according to the Ottawa Citizen,

“A major study of [American] driving records by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety from 1993-2017 also revealed some harsh realities. The report said that 36,760 deaths would have been prevented if limits had not risen — including more than 13,000 on interstates and 23,000 on smaller roadways.”

When British Columbia raised the speed limit by 10km/hr in 2014, the number of fatal crashes doubled. But hey, this is “standing up for drivers.”

The original reason for lowering the speed limit was to reduce fossil fuel consumption; the lives saved were an unexpected byproduct. But that doesn’t matter to Doug Ford; he is part of a world that worships speed and energy consumption. As Vaclav Smil noted in his book Energy and Civilization, all of human development has basically followed a pattern of increased intensity of energy usage, and civilization has basically been a quest for higher energy use. And we are not using the energy rationally:

"Urban car driving, preferred by many because of its supposedly faster speed, is a perfect example of an irrational energy use.... with well-to-wheel efficiencies well below 10%, cars remain a leading source of environmental pollution; as already noted, they also exact a considerable death and injury toll."

Smil believes we have to move toward a less energy-intensive society, but it won’t be easy.

“Such a course would have profound consequences for assessing the prospects of a high-energy civilization—but any suggestions of deliberately reducing certain resource uses are rejected by those who believe that endless technical advances can satisfy steadily growing demand.”

Slow Movements

A low-energy civilization is invariably a slower civilization.

That’s one reason so many slow movements have developed around the world, starting with food. The slow food movement “was founded in 1989 to counteract fast food and fast life, the disappearance of local food traditions and people’s dwindling interest in the food they eat, where it comes from, how it tastes and how our food choices affect the rest of the world."

Other slow movements that I wrote about in now-deleted Treehugger posts (but I got in my archives!) included:

Slow cities- “According to Der Spiegel, "Slow City" advocates argue that small cities should preserve their traditional structures by observing strict rules: cars should be banned from city centers; people should eat only local products and use sustainable energy.”

Slow Travel: “It is happening in Sweden, where 8,000 charter trips were offered this summer, "not just eager eco-travel buffs snapping up the train charter trips, but also a heretofore untapped group of travelers afraid to fly, as well as recent retirees who are nostalgic for the longer train trips of their childhood."

Slow Fashion, meaning “clothing and accessories that start with thoughtfully-chosen beginnings, are constructed by well-paid individuals, and are meant to remain wearable for years to come."

Slow Design, “much like its gastronomic predecessor, is all about pulling back on the reins and taking time to do things well, do them responsibly, and do them in a way that allows the designer, the artisan and the end user to derive pleasure from it.”

And my contribution to the genre,

Slow cars

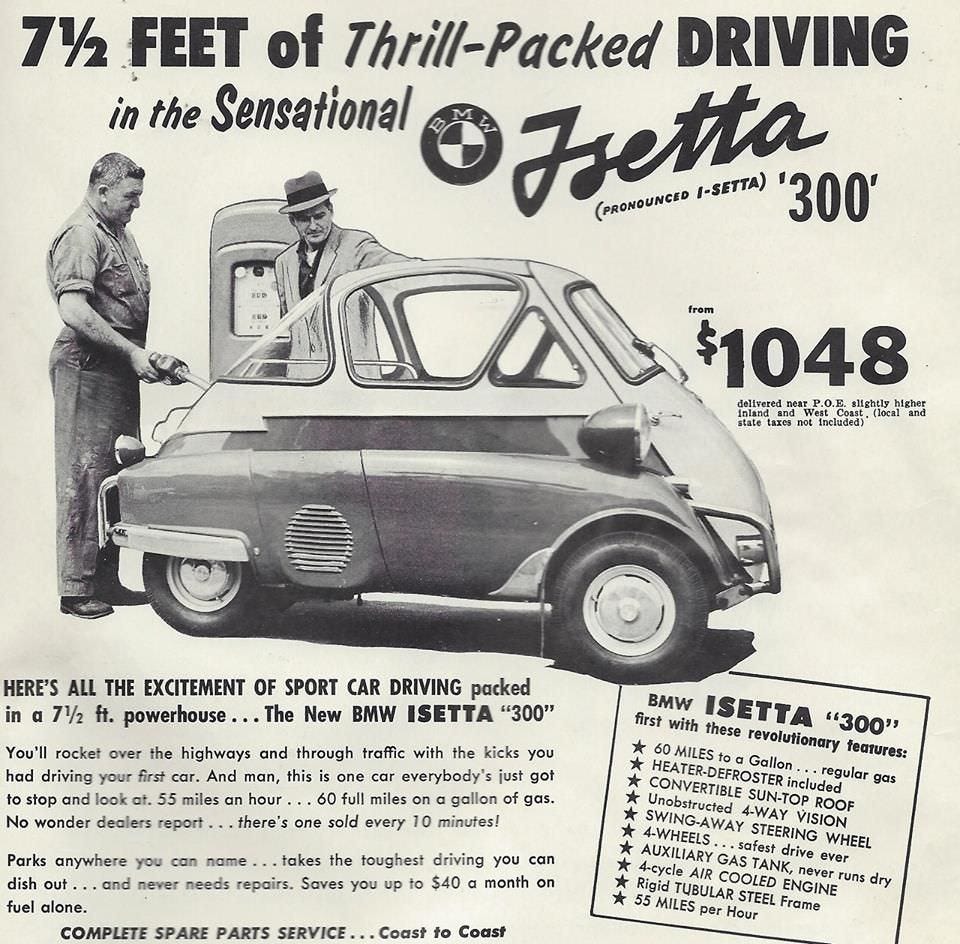

As cars have gotten safer, they have gotten bigger and heavier and way more expensive. In my last years of driving my 1989 Miata, I was terrified to be on the highway; it felt like I could drive under the pickup trucks. About 15 years ago, I admired the BMW Isetta of the 1950s and wondered,

“Perhaps, like the slow food movement, we need a slow car movement, a radical lowering of the speed limit so that the private car can survive in an era of peak oil and global warming, simply by being smaller and slower.”

Being slow, they wouldn’t need all the stuff we build into cars and trucks that go fast, like crush zones and airbags, although, as Mercedes subsequently demonstrated with the Smart Car, tiny cars can be safe.

They take up less space, cost less to buy ($1048 in 1958 dollars is $11,319 today, still cheap!) and have much lower upfront carbon emissions. In our new all-electric world, they could have much smaller batteries.

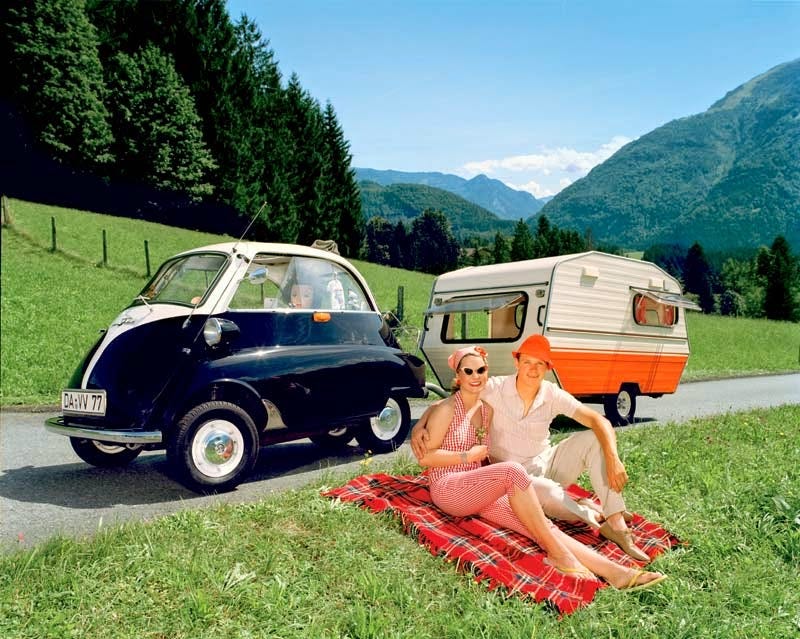

It’s not like you are stuck in the city, either; the whole world is your oyster.

A few years later, when self-driving cars were just showing up on the radar, Alex Steffen wrote The Future of Cars is Slow. He did the math:

“The danger drivers pose to pedestrians, other drivers and themselves is largely a function of how fast their vehicle is traveling. An eighteen wheeler nudging you gently at 1 foot per minute is an inconvenience; one hitting you at 45 miles per hour is probably a death sentence. Slow cars are safer, and when you own a fleet of them in a highly litigious society, safe is a business advantage.”

“Reaction times are shorter the faster a vehicle is going. Even if the “driver” is an algorithm, reaction times count — and for physics reasons alone a car moving 15-20 miles per hour is going to be way easier to safely navigate down a busy street with drivers, bicyclists and pedestrians moving through it than one going 45 miles an hour.”

He pointed out that there were many other benefits, including cheaper infrastructure:

“Roads built for heavy vehicles moving fast are more expensive and wear out quicker than roads designed for light vehicles and slow speeds (there’s also evidence that slow roads are easier to engineer with less polluting and more permeable materials).”

Another benefit of having slow cars is that it will create demand for fast alternatives. Those infrastructure savings could be invested in alternatives to driving. To his credit, Doug Ford’s government is bringing back rail in the north-south corridor that spouse Kelly drives me through when we go north for the summer, which used to be regularly serviced by trains.

Fast trains could be a viable alternative to driving, much as they were 100 years ago.

We have to do something! When I was in Detroit recently, I was astonished at how big cars and trucks being sold as normal transportation had become. I would have trouble climbing into this.

This, seen in New York at the TWA hotel, was far easier for me to get into.

Surely, we have to end this arms race of bigger trucks travelling at higher speeds down wider highways and perhaps slow down and think about what we are doing here. I may have my tongue in cheek with the Isetta, but there is probably a happy medium.

And perhaps Doug Ford should consider the inevitable result of combining higher speeds, more accessible alcohol, and fewer doctors.

Citroen Ami...

The Isetta was my first car and learned to drive in it!