How do we move forward in dealing with the climate crisis?

I spent a summer thinking about what I was going to write about for the next year. Here is what I came up with.

A recent New York Times article titled The Old Climate-Activism Playbook No Longer Works. What Else Can? discusses how difficult it is to get people to care about climate change, in a time when we are essentially going backwards. One of my heroes (and a subscriber!) Earth Day co-founder Denis Hayes is quoted: “You can make a pretty decent case that everything that I’ve worked on in my entire professional life has gone down the toilet in the last six months.”

But the problem goes further back than the last USA election. Interest in climate change and the environment has been waning for years; otherwise, I might still be working for a website named Treehugger. I have been frustrated, and have been thinking about this all summer. When I sit down at my computer to write a post, I often feel like I have been saying the same things for years, just rearranging the words. Nobody seems to care, and nothing changes.

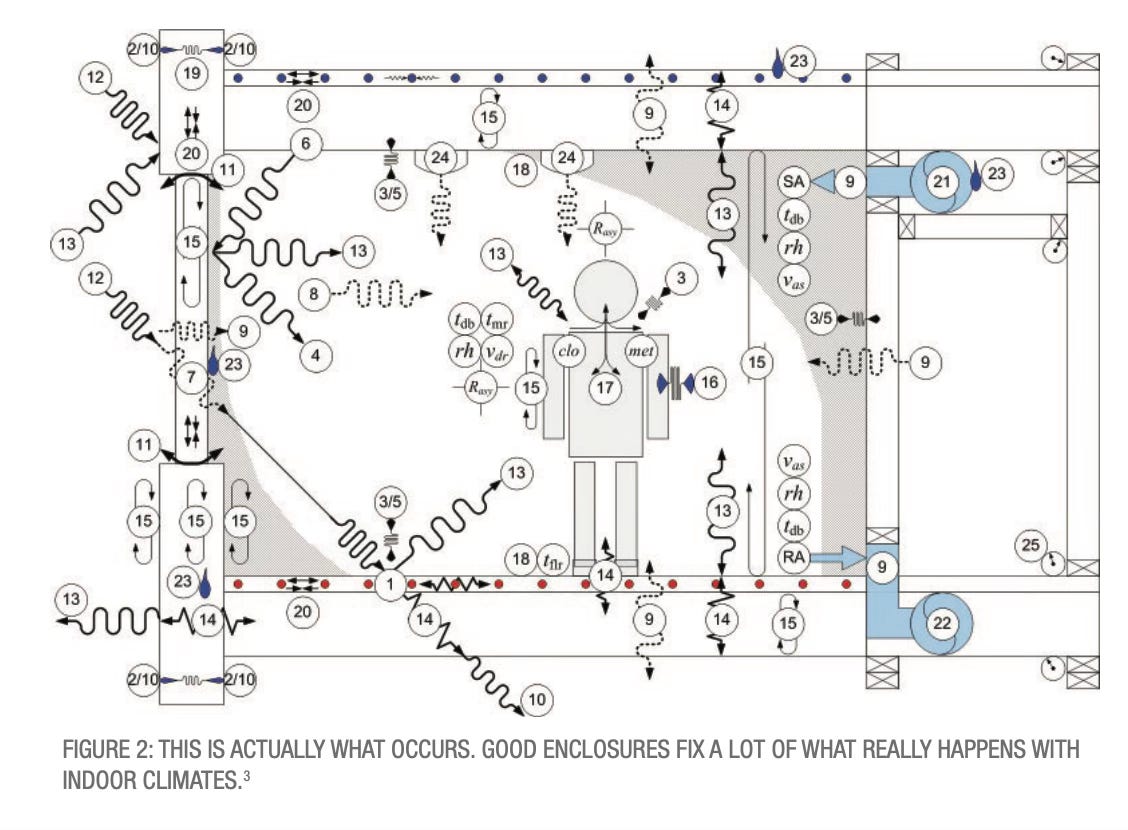

I am not alone in this. Robert Bean has been a profound influence on my thinking about buildings and energy, going back about fifteen years, when I first discovered his website Healthy Heating. He recently noted on LinkedIn, “10 years ago I wrote an essay for Home Energy...nothing has changed except the date.”

He republishes the essay and suggests that only three percent of the industry understands what comfort is.

“Consumers are telling the industry they want comfort and we keep responding with energy efficiency as if the two were synonymous. I'm not a PhD, just a low life technologist trying to scratch out a living, but even I can figure out that if millions of people are looking for comfort from an industry purported to be in the comfort business, better than three percent ought to be able to define it, own the standards and be able to describe the metrics.”

In the article, Robert listed three points explaining why energy efficiency, airtightness, and good windows deliver comfort. It was the reason I became such a fan of Passivhaus; it delivers on these three principles. Yet I suspect that maybe three percent of Passivhaus designers understand why.

Robert wrote an article a few years ago, Integrated Design Illiteracy: The Root of All Evil in Architecture, for a magazine (page 8) that is a great summary of his thinking; you can download it here.

Robert wrote (in 2012): “I have stated multiple times before that building codes need to drop the reference to controlling air temperature and replace it with controlling mean radiant temperature (MRT).” I have been writing about MRT ever since.

A dozen years later, maybe five percent now know what MRT is. And we are going backwards; when people spend money on their homes, they don’t want efficiency or a low carbon footprint, they want comfort and security. Yet now we are pushing Net Zero and “fabric fifth” which deliver neither.

Robert suggests that we start a therapy group for those of us who are banging our heads against the wall. That might help, but during my summer of frustration, I tried to figure out how I got to this place and where I want to go.

In writing my two books, I learned that when you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes. While many are saying “electrify everything,” I became concerned about the upfront carbon emissions from building all the new electric cars and buildings. This is the root of my preoccupation with e-bikes and retrofits.

Even as our buildings get more efficient and our cars more electric, we are still burning more stuff than ever. The so-called energy transition away from fossil fuels doesn’t seem to get any closer, despite all the progress we have made. We are making more stuff than ever, using more concrete, steel, and aluminum, and generating more upfront carbon emissions. Efficiency is wonderful and solar panels are glorious, but this is why we need to ask how much we really need, why we have to seek sufficiency.

Finally, everyone everywhere these days is talking about abundance: “to have the future we want, we need to build and invent more of what we need. That’s it. That’s the thesis.” While the eponymous book is perceived to be leftish, the abundists are putting a new shine on right-wing thinking about unleashing the economy from the burdens of regulation. This is the biggest challenge: to push back against the abundance doctrine, this fantasy of “the future we want” with more of everything. Instead, we need less- less consumption, less stuff. It may not be the future we want, but it is the future we need.

Subscription note:

I usually do a pitch down here, asking people to subscribe. However, it appears that Substack is changing the rules, and subscribers using Apple hardware are being pushed through the App Store and charged a 30% premium. I disagree with this and am looking into alternatives. Please do NOT subscribe until this is resolved.

Great post, Lloyd - against "abundance" and for sufficiency sounds right to me. But it also feels like we are tiptoing around the underlying cause of the attractiveness of "abundance", and that's our capitalist system and culture. It seems that, unless capitalism is disregarded and replaced, a strategy of sufficiency cannot deliver the systemic change required. There are so many crises - climate, biosphere, economic, social, health, and political & public leadership - all captive to capitalism. Seems like we need to be hardcore capitalist abolitionists, but it is hard to imagine how to make that attractive enough to be effective, except perhaps after worst-case scenarios play out. We push on...

"Instead, we need less- less consumption, less stuff."

This is one thing I really believe in, how much stuff have we bought that gets thrown away after a day, week, month, year? Think of all the stuff at the dollar store for kids or storage and etc. Imagine paying a dollar and a quarter for something that came across the Pacific Ocean. Talk about cheap, and where does it end up, in the landfill to decay for 100's of years.