In a world where we should be using less stuff, we are using "more and more and more."

A new book questions whether energy transitions are real.

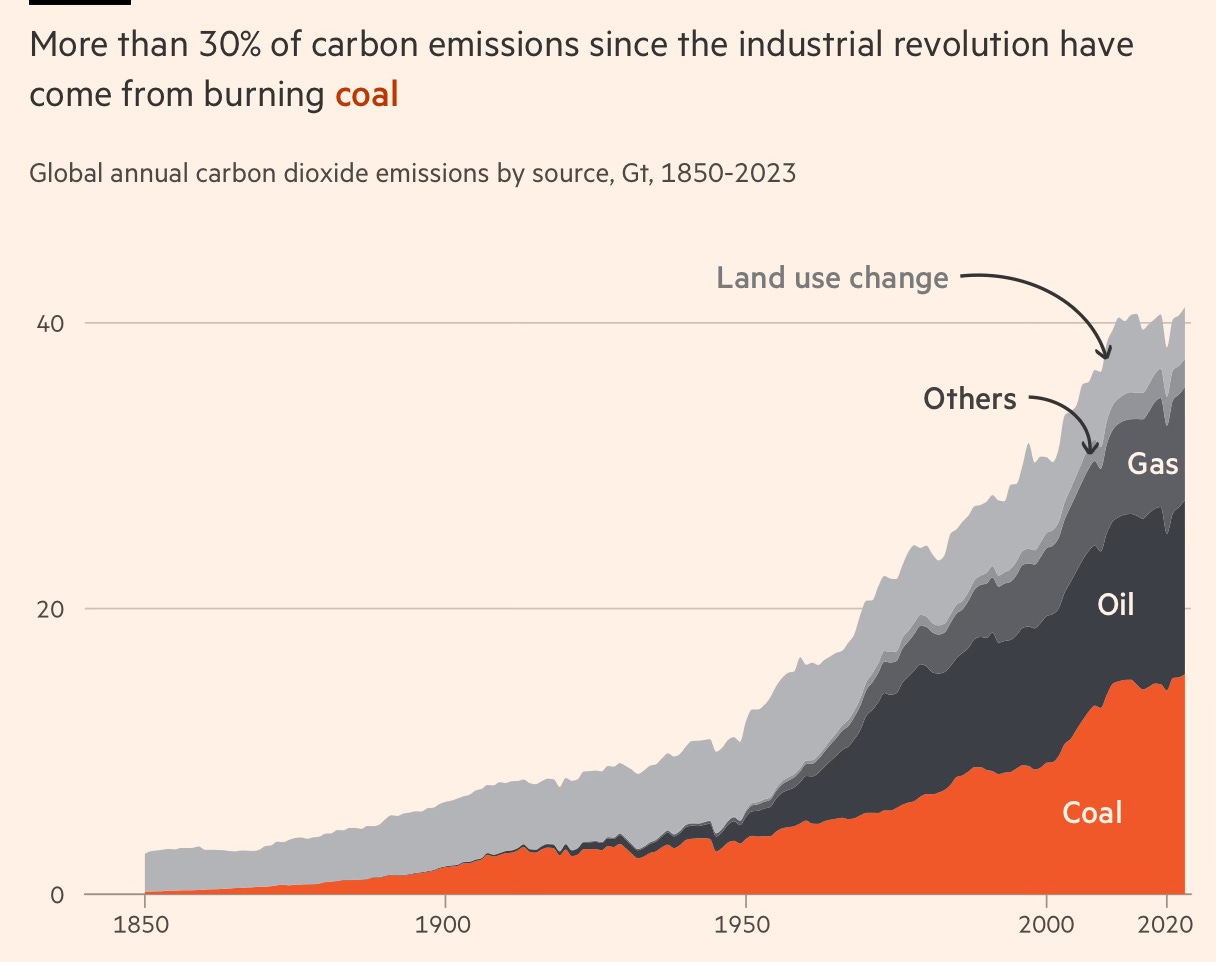

My main goal on this site is to promote the concept of sufficiency, asking “how much do we need?” Because efficiency clearly isn’t enough, we keep burning more and more coal and oil, using more and more resources, to make more and more stuff. Others say we are making an energy transition to renewables, but as I noted in my post “What is the true energy fallacy,” we will need many times the renewables that we have now. Efficiency and renewables simply don’t work unless we have that third leg of the stool, sufficiency.

This is why I looked forward to reading Jean-Baptiste Fressoz’s new book, More and More and More: An All-Consuming History. Fressoz questions whether there has ever been an energy transition from the wood age to the coal age to the oil age to, we hope, the solar and wind age; he explains that we are burning as much wood and coal as we ever have and that it is all additive.

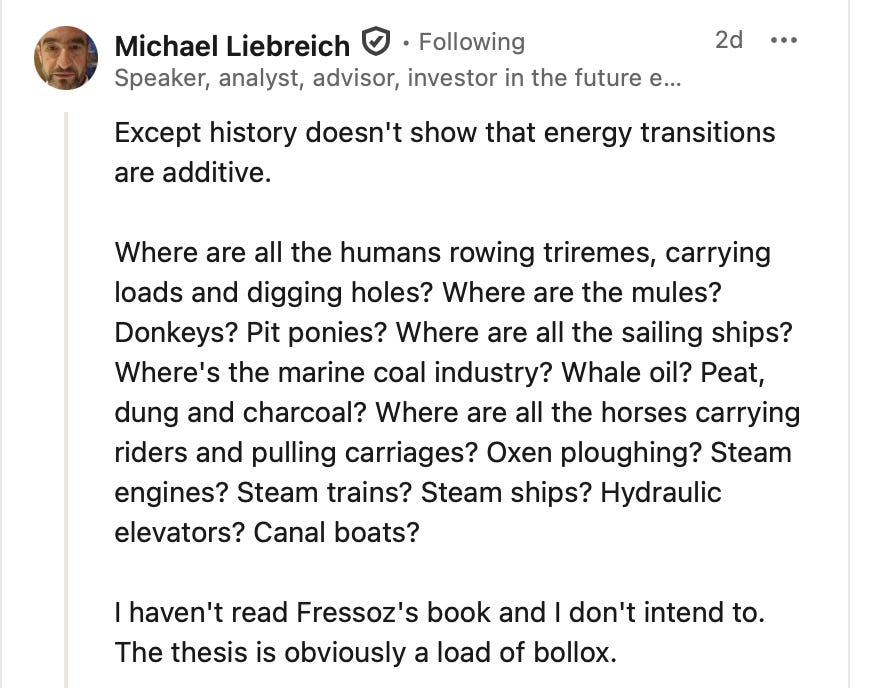

I wasn’t going to review it here because I am terrible at book reviews, and end up quoting endlessly. But then I saw energy analyst Michael Liebreich do a drive-by shooting on LinkedIn:

Liebreich should read the book, because it covers items on his list, including whale oil and charcoal. Whale oil use carried on into the 1970s; it was a fabulous lubricant for everything from watches to jet engines. The transition to diesel fuel for boats made whaling much easier, resulting in a massive increase in production. Its original use in candles wasn’t eliminated by a transition to the oil or gas age; it resulted from figuring out how to turn palm oil into better, cheaper candles.

Fressoz notes also that there has been no real transition from wood; the coal industry used it to prop up mines, and then the oil industry used more of it than anyone else to build derricks and make barrels, and surprisingly, it still uses vast amounts of wood to make charcoal.

In a perfect twist to the transitionist narrative, one of the world’s largest producers of charcoal happens to be the French company Vallourec, a leader in steel tubes for the oil industry. Here, wood is used to produce the steel used to extract oil… Vallourec Florestal now produces and consumes 1.2 million cu. m of charcoal a year, roughly as much as the entire American steel industry at its peak and four times as much as the entire French steel industry at its peak in the 1860s. The mass of wood harvested by Vallourec (around 3 million cu. m per year) probably exceeds the consumption of the world oil industry at the end of the nineteenth century, when derricks, barrels and tanks were all made of wood.

I wondered why they bothered with charcoal when most of the industry uses coke made from coal. It turns out that it contains fewer undesirable impurities like sulphur and results in higher quality steel. In countries like Brazil and Sweden, they have lots of wood and not much coal, and because of weird carbon accounting, “fast” carbon from burning wood doesn’t count while “slow” carbon from fossil fuels does.

As much as a hundred million cubic meters of wood are turned into charcoal every year for cooking and making steel. When people complain about how the transition to mass timber in construction is going to use up all our forests, I will note that all the mass timber in the world right now totals three million cubic meters, a small fraction of what is turned into charcoal.

Even concrete construction uses huge amounts of wood; China consumes 70 million cubic meters of plywood each year just for formwork.

The oil industry also uses vast amounts of steel, as much as 10% of the world’s supply of steel, much of which is made with coal. They didn’t transition from coal; they just used more of it. Even if that oil is not powering cars because they are electric, the cars are made of coal.

“In total, the automotive industry accounts for around 15 per cent of global steel flows, three-quarters of which is produced from coal – 1 billion tonnes in all. In China, where almost a third of the world’s cars are produced, life-cycle analyses indicate a consumption of around 2.5 tonnes of coal per car.”

The roads and bridges they run on are made of concrete, which is made with coal, and asphalt, which is made from oil.

Steel, concrete and plastics are the backbone of our economies:

“Wind turbines and solar panels are remarkable technologies for producing electricity, but they are of little use in the production of these key materials. To believe that innovation can decarbonize the steel industry, cement works, the plastics industry and fertilizer production and use in thirty or forty years, when recent trends have been the opposite, is a very risky technological and climatic gamble. Taken together, steel, cement, fertilizers and plastics account for more than a quarter of global emissions, enough to put the Paris Agreement target out of reach.

Fressoz believes that the idea of “transition” is illusory; we are burning more wood and coal than ever. Talk of the transition is no different from talk about carbon capture and storage- what Alex Steffen calls predatory delay. It lets us keep consuming more stuff, say an electric car rather than a gasoline-powered car, when in fact we should be thinking about living without so many cars.

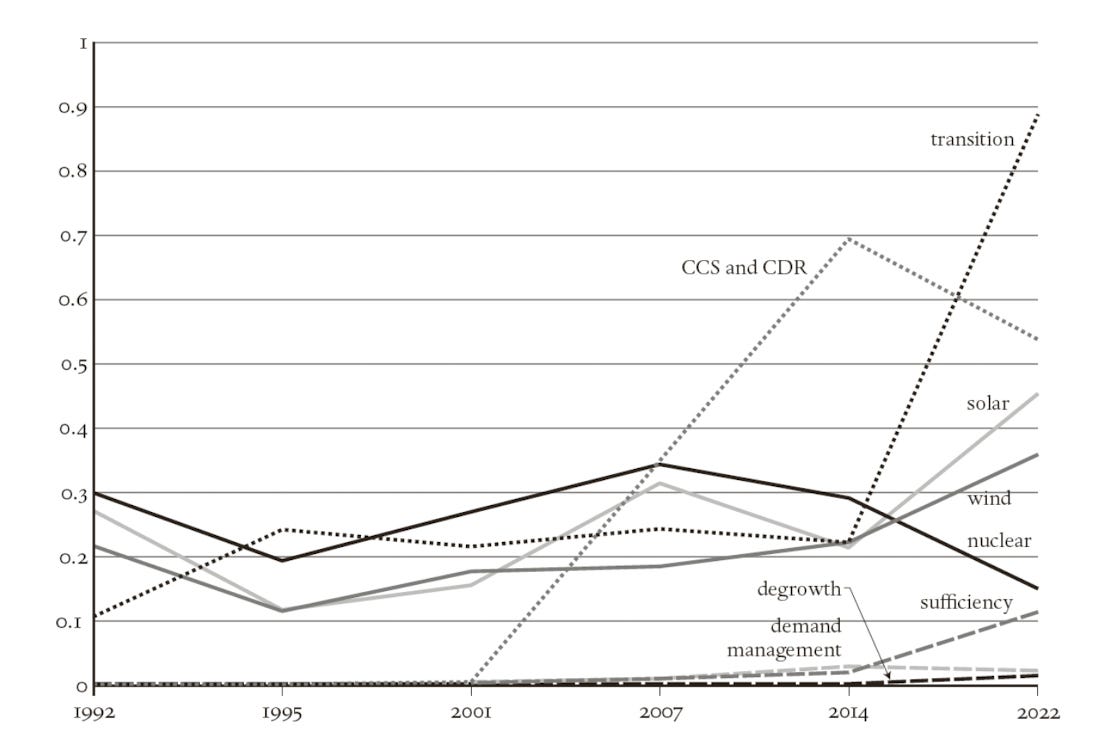

Fressoz complains that the IPCC pushed transition and ignored demand management and sufficiency until the 2022 Mitigation report, which I called a Prescription for fixing the Climate Crisis.

All of the IPCC Group 3 reports are dominated by technological discussions; “demand management” is mentioned 1/20th as often as “carbon capture,” and look where “transition” is.

Demand management and sufficiency don’t need as much technology; you reduce demand, use less stuff, fix what we have. For example, instead of filling concrete highways with electric cars and everything that goes into them, we design our cities around people on foot or on e-bikes. Fressoz concludes:

“Thanks to transition, we are talking about trajectories to 2100, electric cars and hydrogen-powered aircraft rather than material consumption levels and distribution. Very complex solutions in the future make it impossible to do simple things now. The seductive power of transition is immense: we all need future changes to justify present procrastination.”

Which brings me back to Michael Liebreich, and his final statement, “It won't take a decade for Fressoz and his promoters to look foolish.” I suspect that within a decade, people will realize we can’t keep consuming so much of everything. We have to drastically reduce primary demand for steel, concrete, and plastics because of the wood, coal and oil they are made from. It’s all in the title; Fressoz says we are using More and More and More, when fundamentally, we have to use less stuff.

I think Liebreich should read the book. It is a very different take from Dan Yergin’s, which he covered in a recent article. He might even appreciate Fressoz’s “pragmatism of robust but affordable climate action.”

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35- US$37-the dollar is falling ). I am running out of stock, so hurry!

Great to see this write-up. I'm halfway through he book and it is a sobering corrective that I didn't know was necessary. The author convincingly demonstrates that it may be a wee bit foolish to bet on an energy transition in the future, when it's really never happened before. Liebreich sounds particularly cartoonish as Frezzos says up front that because transition is illusory, what we require is wholesale systems/cultural/economic transformation to, yes, use much, much, much, less energy. The book rightly places us in the quicksand our economic system has trapped us in. No rainbows and unicorns.

Grim on more & more & more…