Happy 10th birthday and happy Earth Day, Bullitt Center

The world's greenest office building still sets the standard after a decade of operation.

The Bullitt Center opened its doors in Seattle on Earth Day in 2013. It was called the world’s greenest office building then, and it likely still is. It was designed by Miller Hull to the tough Living Building Challenge Standard; Lindsay Baker, CEO of the International Living Future Institute, which runs the LBC, says:

“The Bullitt Center lives forever as a moment in time when the gauntlet was thrown down. People thought the building was impossible until it existed. It shifted the paradigm about what’s possible in dramatic ways and got people thinking about what buildings could and should do.”

Denis Hayes, the coordinator of the first Earth Day in 1970 and now the CEO of the Bullitt Foundation, says, “We were told point blank by seven well-respected developers that a six-story office powered entirely by the sun was impossible in Seattle. I’ve never put much stock in conventional thinking.”

I visited the Bullitt Center in 2015 and got a tour conducted by Brad Kahn, who is still involved. I had some questions and concerns at the time and have watched the building evolve. Much has changed in ten years in the green building biz, but this building still has stories to tell, and Brad kindly answered my questions.

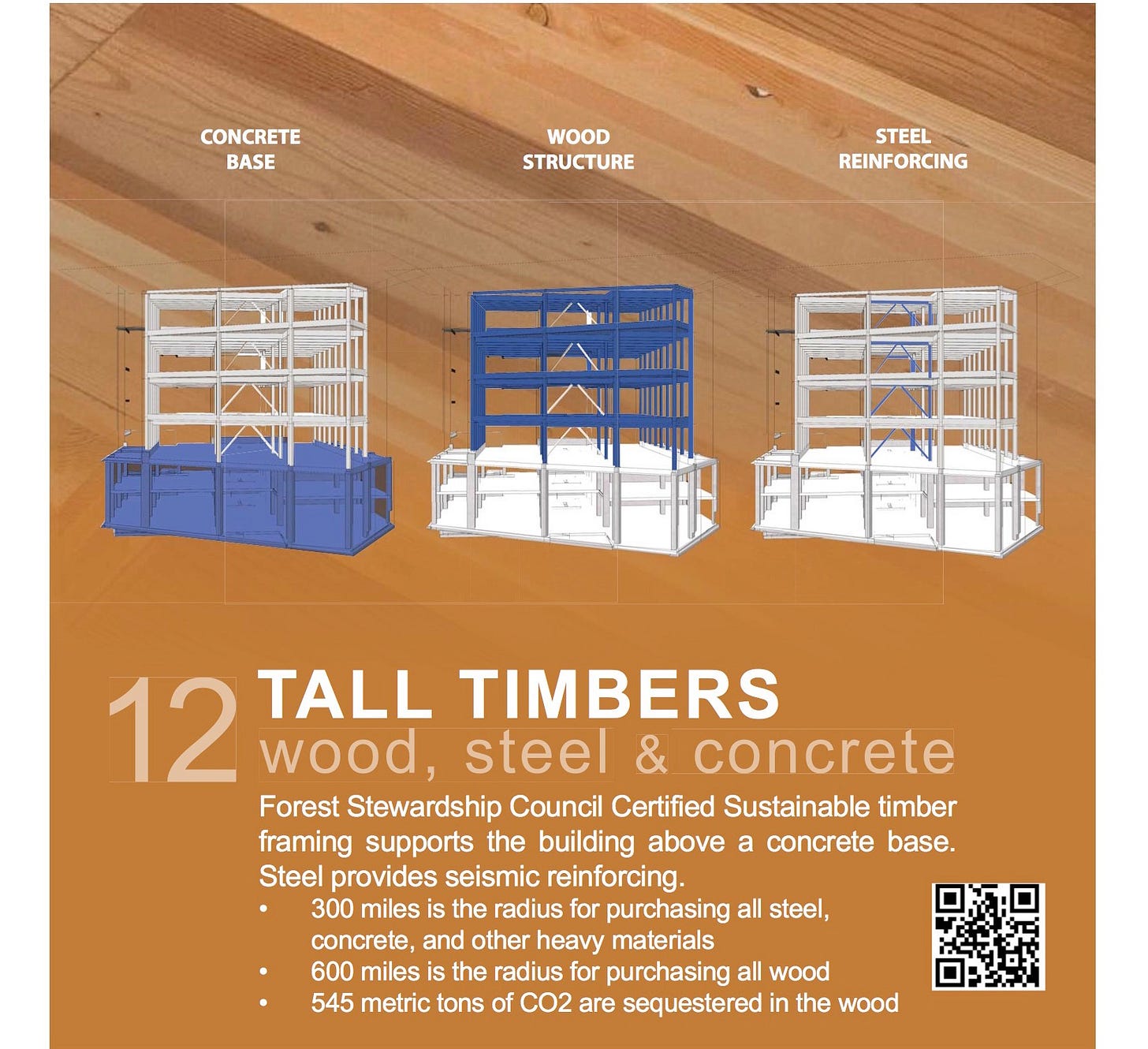

The building was an early modern mass timber structure, with nail-laminated decking supported on glue-laminated beams. They wanted to use cross-laminated timber, but it wasn’t approved at the time, whereas NLT, formerly called mill decking, is in every code and has been used in warehouses in Seattle for 150 years. It was the first modern mass timber building I had ever been in.

NLT was thought at the time to be less innovative and sexy than CLT, but it’s come into its own; Miller Hull used it again on the Kendeda Center in Atlanta where they mixed new 2x6 wood with salvaged 2x4 to make a stunning ceiling which looks even better than CLT, and was assembled by local labour.

Today, many companies are producing healthy building materials; a decade ago, it was hard to find products that didn’t have “red list” chemicals. Take that blue sleeve connection on the drain pipe; you can go to the Home Depot and pick up a neoprene one, but the foamed plastic is on the red list. It took time and a lot more money to bring this one in from Europe.

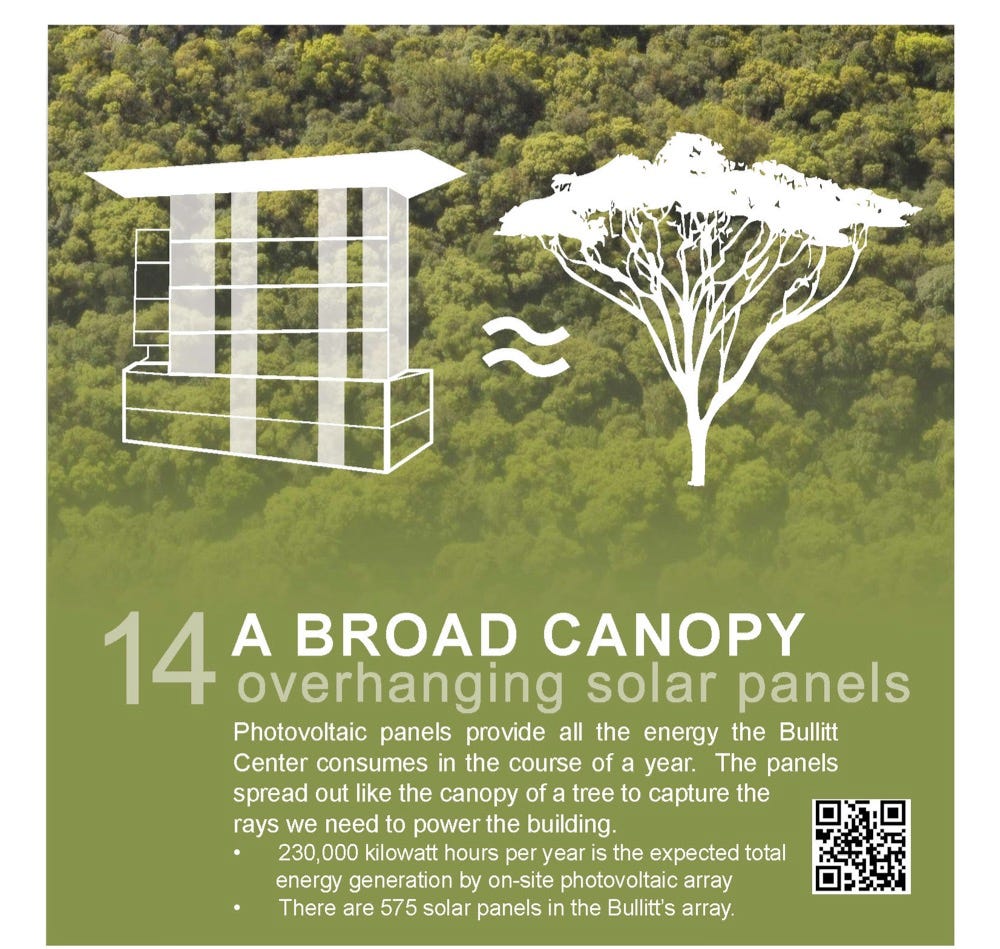

One of the most dramatic features of the building is the solar hat, extending out beyond the building and the property line. This troubled me; blocking the sky over public property is not a good precedent.

In the press release, Brad says, “In ten years, the Bullitt Center generated 2,475,021 kWh of energy, which was 551,481 kWh more than the building and its occupants used for all purposes.” In ten years, lighting and computers have become more efficient, and they had so much electricity to spare; I asked if they needed to have extended beyond the building. Brad responded:

“Maybe, depending on our goal. To hit net zero energy on an annual basis, we needed the current array in a couple of years (2018/2019) when office occupancy was at its peak. in particular, we had tech-intensive tenants who filled their spaces with high-powered computers. All things being equal, the array was appropriately sized to our goal of net zero energy on an annual basis.”

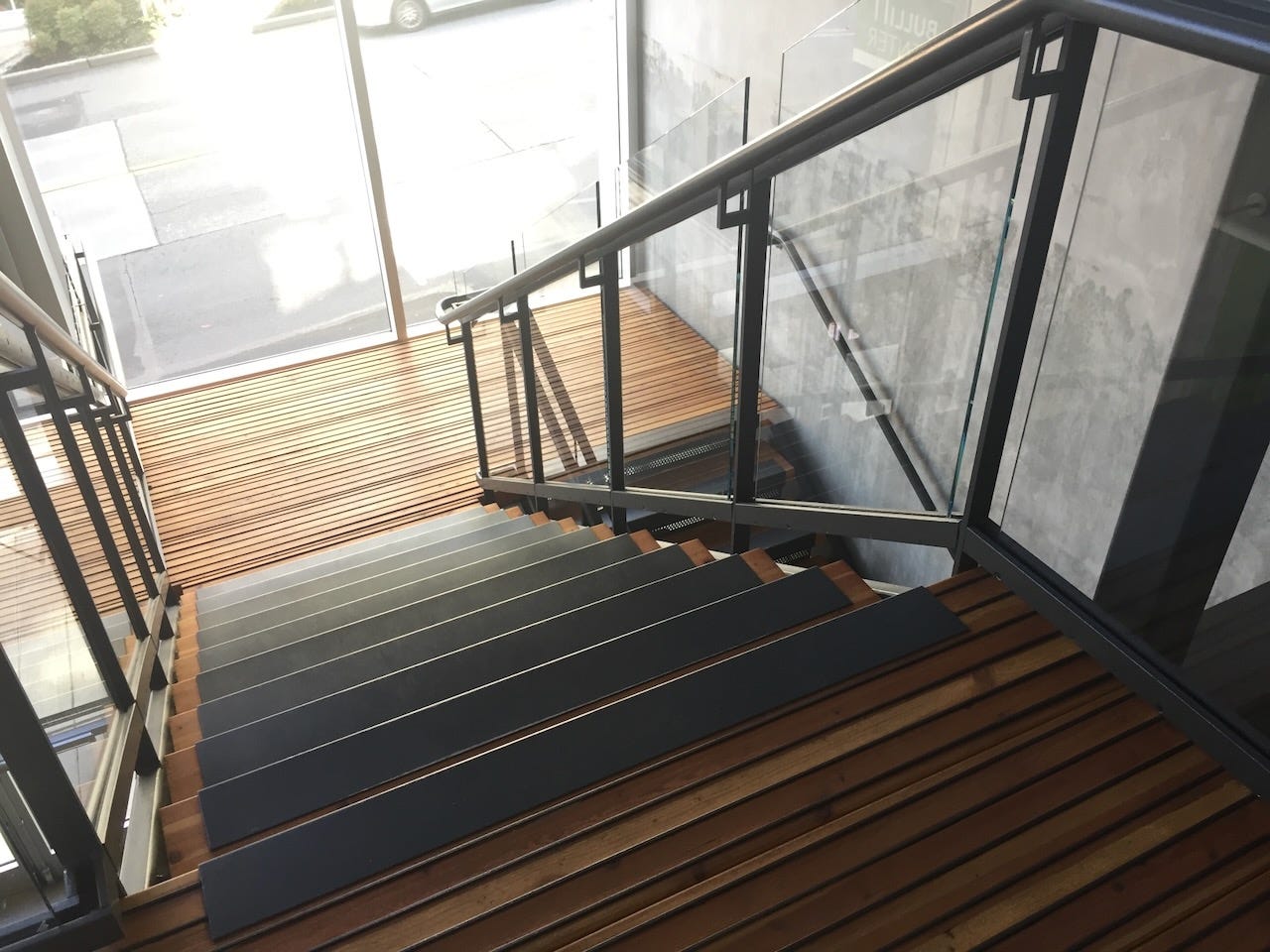

Another prominent feature was the stair. I wrote at the time:

“In most buildings, the stairs are buried in the interior. At the Bullitt, "active design" is part of the program, with this "irresistible stair" at the entrance of the building, designed to encourage its use. They claim that "This stairway has near-magical powers: people can’t seem to resist going up." It is a beautiful stair, all crafted of wood and steel and enclosed in glass, but I found it a bit scary near the top, seeing all the way across Seattle to the mountains.”

Ten years later, many architects and builders have learned this lesson. There is Fitwel certification to encourage people to use stairs, and during the pandemic, many people chose stairs over elevators. The stairs at the Bullitt are a bit less scary, too; they appear to have closed the open risers and replaced the treads.

The Living Building Challenge requires dealing with waste on site, so the building had composting toilets, a feature I was a big fan of; I called their washrooms "the sweetest-smelling loos I have ever been in." That’s because they are constantly sucking air down into the toilet.

Alas, they have all been removed; I wrote about this on Treehugger, noting the functional problems they had- not enough room for servicing, management problems because men poop more than women, but as I wrote earlier, I believe the real problem was cultural- In Europe, there are brushes beside every toilet. They say: "From a European perspective: why don't toilets in the US ever have a toilet brush in the bathroom? I can't leave the toilet like that!!" But Brad notes, “The composting toilets were a leading cause of complaints, mainly due to soiled toilet bowls. office workers are not inclined to touch a toilet brush, it seems.”

Denis Hayes was nonplussed: "We integrated lots of bleeding-edge technologies. If everything had worked perfectly, that might have meant we hadn’t been bold enough."

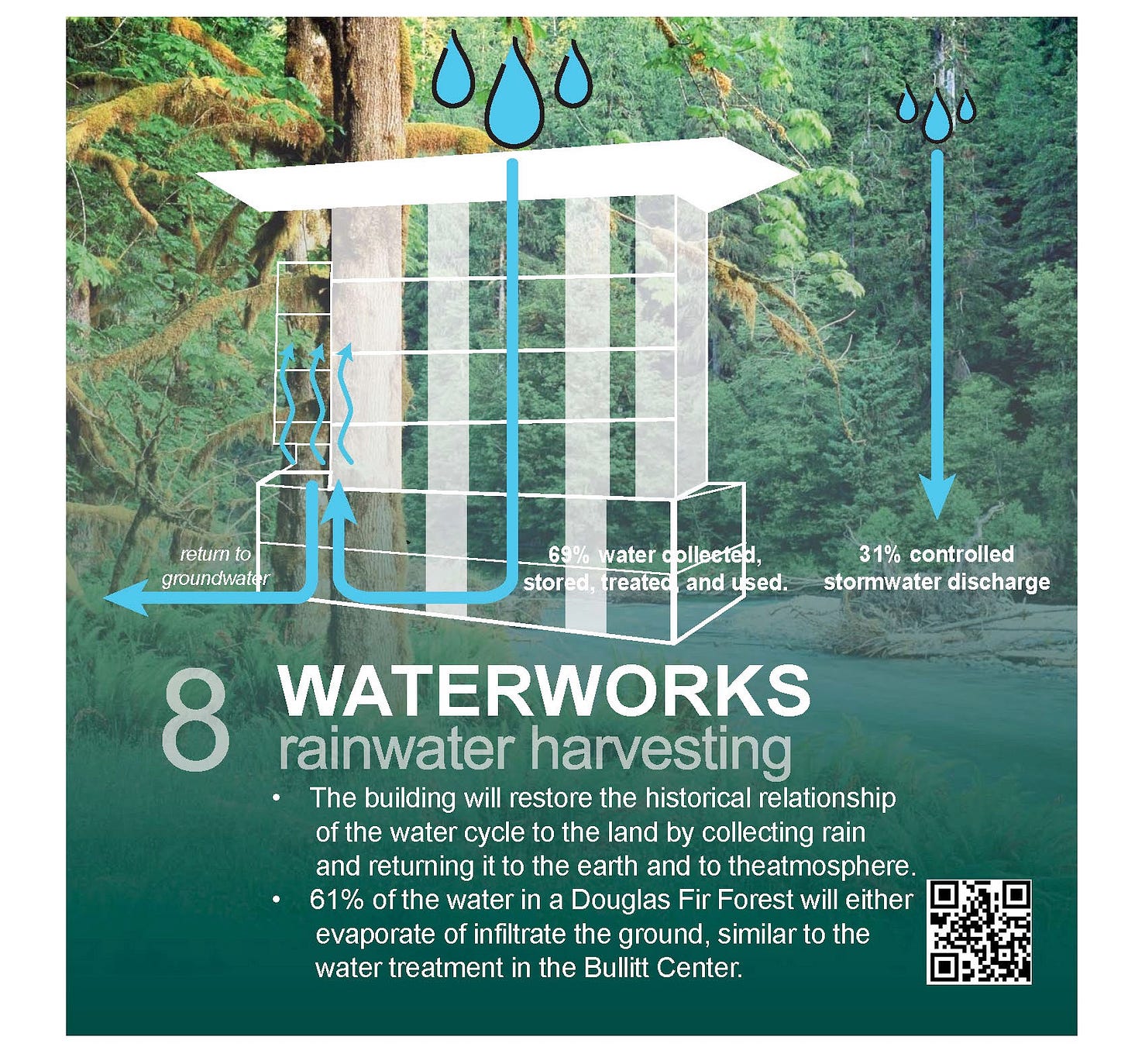

My least favourite feature of the building was the water system. The Living Building Challenge water petal at the time required that everything be done on-site, including gathering and purifying rainwater. So here we are in Seattle, with some of the best drinking water in the world coming off nearby mountains, monitored constantly.

Instead, at the Bullitt Center, they gather water and everything else that falls on the solar panels, filter it and are required by law to chlorinate it. Except chlorine is a red-list chemical and so they then have to dechlorinate it. They have a 56,000-gallon cistern to hold it all. The system wasn’t working when I was there; it took years to get approval.

I believe that the Living Building Challenge was wrong about water; we shouldn't privatize it. Water is a public service, usually carefully monitored and cleaner than bottled water. If you're part of a larger community with a safe municipal water supply, you should use it. There are some things we do better together; otherwise, you end up with Flint, Michigan and Walkerton, Ontario.

Brad says the system is working now and points out the value of that big tank.

“Arguably, the system is at least as important for stormwater mitigation. At the scale of one building, it does not make much impact on Seattle overall, but if more buildings had cisterns, we could avoid a lot of investment in infrastructure. for example, Seattle is currently spending close to $2b on a large cistern to capture stormwater to avoid polluting Puget Sound. If instead, the city had required cisterns in all new construction, with a centralized way to manage them, the same capacity could have arguably been developed at a much lower cost.”

But he also lists as a major lesson learned: “Don’t install a rainwater to potable water system before the public health department approves the system.”

The building didn’t have any car parking spaces, but it did have a gorgeous bike room. The one in the foreground was Brad’s e-bike; there were no electrical outlets in the garage, and Brad had to remove the battery and take it to his desk for charging. Brad advises that there are now outlets. As an e-bike evangelist today, I laugh now at the words I wrote in 2015:

“These are going to be seriously fit people; I walked there, and it was uphill all the way. Brad Kahn, who conducted my tour, commutes seven miles each way on this electric-assisted bike. I usually think these are for wimps but not in this town; I would get one here for sure.”

There are so many other things to admire here. Constructed wetlands wash 400 gallons of wastewater per day; Ground source heat pumps heat and cool, with extra holes drilled in case an earthquake breaks a few; the building is designed to last 250 years so they might need a spare. Exterior shutters keep out the sun; as architect Mike Eliason has written,

“There is effectively no active solar protection industry in North America. Power outages will increase in the future, especially during heat waves. How will building occupants keep cool when they cannot even keep the sun out of their buildings? Operable external solar protection offers a level of climate adaptiveness that planners and policymakers need to be thinking about in a warming world.”

Lindsay Baker said, “The Bullitt Center lives forever as a moment in time.” However, that moment is now a decade. It is still a role model, it is still an example of how we should think about buildings, and ten years later, most architects and builders are still ignoring its message. I asked Brad Kahn about the lessons learned:

“Examples alone do not change dominant construction paradigms. Most buildings are still wildly inadequate to meet the climate challenge. Codes still rule the roost and in the vast majority of cities, codes are far too lenient. The building sector needs to turn to advocacy and policy change if we hope to address the 40% of emissions tied to buildings. We are a leading contributor and other than a small number of examples, the building sector still contributes massively to climate change.

The Bullitt Center has arguably changed as many minds as any building in a generation. and yet, even in Seattle, most buildings are virtually obsolete the day they are built. We have to do much better, and the era of “carrots” alone is now behind us. We need more “sticks” to force the development of buildings that meet the climate imperative.”

Denis Hayes should be a happy man on this day, but he concurs with Brad:

“While I am thrilled with the way the Bullitt Center has performed, I am deeply saddened by the lack of progress in buildings overall,” said Hayes. “Despite obvious signs of climate change everywhere, we continue to race towards a cliff.”

But we do have the Bullitt as a beacon. Happy Birthday and Happy Earth Day, Bullitt Center and Denis Hayes.

Likewise, thirteen years ago, when I was with Sasaki, I led the design of the first ZNE laboratory building in the Northeast US at Bristol Community College, completed in 2016. Since then, such buildings have become commonplace. Of course, I wish I'd had a greater appreciation of embodied carbon, because there are a number of decisions that I would have made differently.

Great reflection Lloyd - I’ve always been curious about the inner details of this building - hard to believe it’s been 10 years.