Even with LEDs and e-bikes, we have to ask how much we need and what is enough.

"Efficiency without sufficiency is lost."

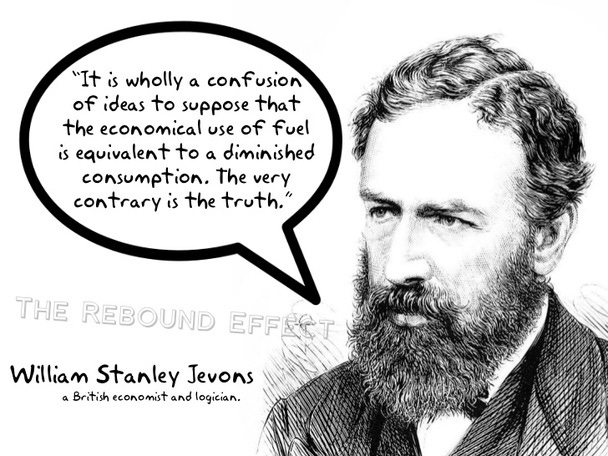

The Wall Street Journal recently published an article by research scientist Carey King titled Why Energy Efficiency Might Not Reduce Carbon Emissions as Much as People Think, in which the author invokes Jevons’ Paradox.

“A case can be made that strategies that rely heavily on energy efficiency to reduce emissions are bad bets. Historical data show that increased energy efficiency has gone hand-in-hand with more energy consumption over the long term, not less, and I would argue that any decarbonization approach that fails to take this into account runs the risk of backfiring.”

It’s not surprising that poor Stanley gets dragged out in the Journal; he is beloved by those who want to convince us that energy efficiency measures are pointless. King claims, “My own research shows that it takes about six years, on average, for improvements in energy efficiency to lead to higher overall energy consumption.”

I have often noted that greater efficiency has given us bigger cars, bigger houses, and in the most extreme example I can think of, The Sphere in Las Vegas. I have argued with Zack Semke of the Passive House accelerator for years about this (see comments to the Sphere post), with Zack noting that when they get more efficient, people don’t get a fridge that’s twice as big or drive a car twice as far, and even if the Sphere is excessive, LEDs still cut energy consumption. King gets this and notes,”Critics who dismiss Jevons’s idea often focus on consumer behavior.” But it is different at the industrial scale.

“When you zoom out further to the global economy, however, you see that industry reacts much differently to increasing efficiency. More efficient firms generate greater profits, which leads to more investment, more production and, crucially, more energy consumption to support more food production and population.”

What is interesting and different in King’s argument is that he doesn’t dismiss efficiency; he suggests it has to be tied to other measures that restrict the growth of energy consumption.

“If growth is the goal and you want to spur more of it, then keep promoting investment in energy efficiency with no other policies to restrict profits and investment. But if the goal is to balance growth with lower greenhouse-gas emissions, you have to direct investments toward low-greenhouse-gas technologies and away from high-greenhouse-gas technologies by penalizing emissions.”

That’s not quite a call for degrowth, but it is a call for restraint, balance, and maybe a big carbon tax.

I and others have called for policies that promote sufficiency, along with efficiency and a switch to renewables. (the SER Framework.) I have quoted Australian philosopher Samuel Alexander, who wrote, "Efficiency without sufficiency is lost." Alexander writes in his wonderful Critique of Techno-optimism:

"What is needed, at a minimum, is for rich nations to stop redirecting efficiency gains into production and consumption growth. Instead, efficiency gains must be used to reduce overall energy and resource consumption. For example, technologies that increase labour productivity should generally lead to decreased working hours, not increased production; technologies that increase energy efficiency must not be used to ‘do more with the same inputs’ but to ‘do enough with fewer inputs’."

Alexander is using sufficiency and Jevons in a call for degrowth. I like to make a case for “less, but better.” In my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, I picked a different Jevons quote than the usual one in the image above:

William Stanley Jevons wrote in “The Coal Question:”

There is hardly a single use of fuel in which a little care, ingenuity, or expenditure of capital may not make a considerable saving. But no one must suppose that coal thus saved is spared – it is only saved from one use to be employed in others, and the profits gained soon lead to extended employment in many new forms.”

So if we make things more efficient, we get more profits and more consumption instead of less. Our houses and cars all got bigger, and we used our savings to get more stuff to fill them with.

But there are two sides to every equation. Jevons also noted that when a resource gets more expensive, we use it more carefully. “It is true that where fuel is cheap it is wasted, and where it is dear it is economized.” Thus, when oil prices went through the roof in the seventies, we got the pivot to Pintos and small fuel-efficient cars and the Japanese invasion. When oil prices went down and engines got more efficient, we got SUVs.

Jevons works both ways. As lithium supplies tighten and the costs go up, batteries get new chemistries that use less lithium, and get greater energy density. They are also being used, as Jevons predicted, in many new forms; we have seen the explosion in micromobility, with e-bikes, scooters and mini-cars doing the same job of moving people with a fraction of the materials.

Stanley Jevons teaches many lessons:

Making the steam engine more efficient didn’t lead to a reduction in coal use; it led to an explosion in creative new ways to use the steam engine, the Industrial Revolution, and the modern world, including our current climate crisis.

Making the lightbulb more efficient has led to a reduction in electrical consumption for lighting but also an explosion of uses for the LED, ending up with The Sphere and other weird and wonderful uses of LEDs, which are probably eating up much of those savings.

Making batteries more efficient made my beloved e-bikes possible, but where they used to be “bikes with a boost,” they are now faster and heavier and more dangerous, closer to motorcycles than bikes, and we are facing an “e-bike-lash.”

King concludes in the WSJ: “Energy efficiency is a valuable tactic for improving well-being by expanding access to energy services. However, we must confront its unintended consequences.” I agree; even with the greenest of concepts, from LEDs to e-bikes, we have to ask what is enough, what is sufficient, what do we really need.

The title is an efficient and sufficient way of conveying a deep truth. Until we decide that there is such a thing as enough when it comes to material wealth we will continue on the fast track to oblivion.

Electricity is better energy than fossil fuels because there is far less heat loss, but it does make for a more diverse set of products that everyone wants. Like you, I ride an e-bike a lot. It makes biking possible for us old guys who would love to have the energy to challenge our hills, but don't. However, I don't need a designer e-bike for every type of riding: cruiser, cargo, folding commuter, mountain, etc. General purpose is enough. Degrowth is a must, but it requires an economy designed to contract without collapse. Depression is not a recommended solution to over consumption. Perhaps we can find the Howard Odum-David Holmgren idea of "a prosperous way down". That is greatly preferred to the dysfunctional chaos we inevitably face with the Trumpian mistake in the US. Capitalism in its totally free market form is basically a Ponzi scheme, and I fear the end game is coming.