Bonus: How Did Our Fridges Get So Big?

From the archives: The big fridge, the big car, and the big grocery store are all part of one economic machine; in a sense, you cannot have one without the other two.

I recently wrote about kitchens of the future and the role of refrigerators. I previously wrote about fridges for my former employer who chose to remove it from the site, so I am restoring it here from my archives. From early 2000 during the height of the pandemic. Some links may not work.

The pandemic and the lockdowns have changed the way many people use their kitchens, and designers are rethinking them as well. I have noted in a previous post on design trends that people are cooking more, and that preparing food has become more of a family affair, so I have been forced to reconsider my case for closed, rather than open kitchens.

I have also been forced to reconsider my thinking about the refrigerator as well. For years I tried to make the case that small fridges make good cities, that "people who have them are out in their community every day, buy what is seasonal and fresh, buy as much as they need, responding to the marketplace, the baker, vegetable store and neighborhood vendor." That's how people live in much of Europe, and that is mostly how our family lived in Toronto. But it became clear that fridges are like cars; they cannot be separated from where we live, and are part of a larger system. I had to reverse my thinking when I realized that good cities make small fridges.

However, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we use our cities. In our own home, spouse Kelly is now shopping once a week, and by Tuesday the refrigerated cupboard is bare. The martini glasses that had the freezer to themselves have been pushed out in favor of food that Kelly has frozen. My colleague Katherine Martinko notes that her family's cooking and eating habits have changed too; the pandemic is changing life in small towns as well, and many of these changes may well be permanent.

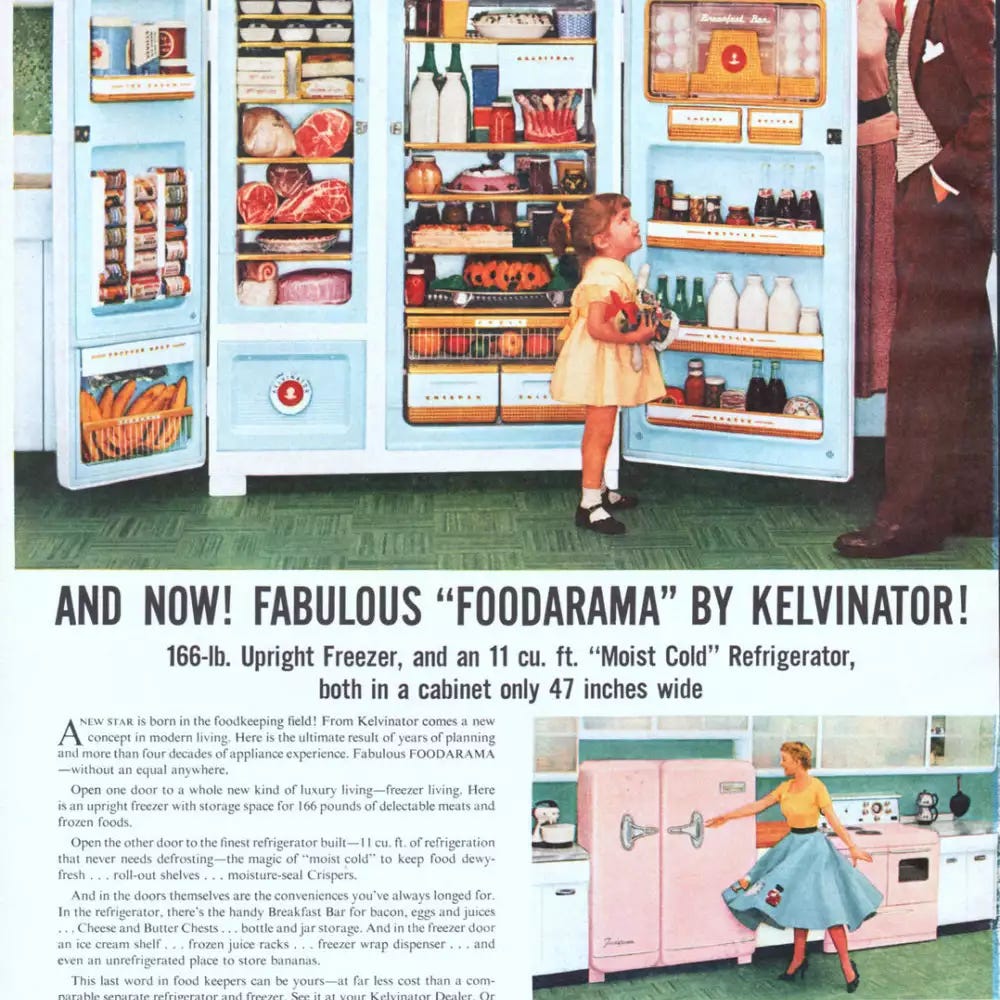

It's not the first time this has happened. While looking into the history of the Kelvinator Foodarama, the amazing giant fridge from the 50s that had a place for everything, I stumbled across an essay titled Visions of Plenty: Refrigerators in America around 1950 written by Sandy Isenstadt in 1998. It starts by describing the thinking of Industrial Design magazine founder and editor Jane Fiske Mitarachi, who thought in 1954 (as I have) that modern technology would make kitchens disappear.

"With cheap energy and miniaturized appliances, food preparation could be dispersed and meals could be taken at the family's leisure, outside as easily as inside. Consequently, the space of the kitchen could be used for a variety of other purposes. The kitchen, she concluded, was disappearing altogether. Except for one thing – the refrigerator."

Mitarachi knew something about food; she later went on to be Jane Thompson, who was a partner in the design firm that developed Faneuil Hall in Boston and the South Street Seaport in New York. She may have been wrong about kitchens, but she was right about fridges.

Isenstadt continues with a discussion about how the closed fridge might blend into the kitchen landscape, but when open, was a window to another world.

"Like a view, Kelvinator's 'Foodarama' was able to 'bring the outdoors indoors' by presenting a culinary rainbow within the kitchen. Ad copy, a 'panorama of foods at your fingertips', repeated the view's pictorial creation of depth within an arm's-length... Opening the door of the refrigerator was likened to throwing open a window, in fact, 'a big bay window', on to a landscape of material abundance and prosperity, territory both vast and agreeably convenient. Ease of movement between inside and outside, between hunger and satiety, brought the natural landscape that much nearer."

The Foodarama was a marvel. You started your day at the breakfast bar (6) for your bacon, eggs, and juice. It promised fewer shopping trips, better meals, easier meals. It even had a place for bananas (8), in a non-refrigerated section in front of the compressor. There was a place for everything that the supermarket had to offer. Isenstadt notes that "the refrigerator of the 1950s encouraged consumption even as it made the infrastructure of consumption invisible."

"Though developed during the 1920s, the supermarket took off only after the end of wartime food shortages and the beginning of post-war suburban growth. With their low profit margins and rapid turnover of merchandise, supermarkets quickly became the focus of intense marketing research aimed at improving sales... The refrigerator functioned as off-site inventory storage for a growing food industry. To facilitate this, it was portrayed as consumer empowerment: flattening temperature variations, keeping foods 'indefinitely', meant more efficient use of domestic capital. As an in-home showcase of the greater market, the refrigerator of the 1950s was a tableau of the industrialized food chain, a visualization of a capitalist landscape.

The big fridge, the big car, and the big grocery store were all part of one economic machine; in a sense, you cannot have one without the other two. And as the stores got bigger, so did the cars and the fridges, mainly by using better insulation and having much thinner walls. The system was built for suburban living, with more space for more storage, for people who had the cars to carry the bigger and heavier packages with lower prices. And it was built to encourage us to buy, store and consume ever-larger quantities of food. Isenstadt concludes:

"When the door of the 1950s refrigerator was shut, the entire unit receded, vanishing among the flush surfaces and polished metals of modernist aesthetics. But the moment hunger pressed, the refrigerator unfolded, seemingly by itself, into a vision of gustatory plenitude: an instantly edible spectacle, with every snack a story of material well-being."

This was written in 1998, but Sandy Isenstadt is still writing and is now teaching the history of modern architecture at the University of Delaware. He tells Treehugger that the refrigerator piece was the first thing he ever published and that he had a lot of fun writing it. I contacted him to see if he had any thoughts about fridges and the pandemic, and he replied:

"I’ve only kept a cursory eye on the kitchen changes wrought by the pandemic so I don’t know that mine is a particularly insightful view. I do think people have spent more time cooking and, certainly, baking. I know I’ve been doing that. I can’t say I’ve gotten any better at either, though, but it’s been fun. I’d hate to think the pandemic has led to larger fridges – fewer trips to the grocery store but larger purchases – but maybe that would be an outcome. I’ve definitely tried to reduce the number of times I venture to the store."

I am not happy about the pandemic leading to larger fridges, but I suspect it has, along with a spare in the garage. The pandemic has probably changed more than a few habits.

And in case you are shopping, here is the commercial, starring 50s TV star Hillary Brooke.

I just went through the experience of living in an AirBnB with a smaller refrigerator--not a dorm fridge, but a shorter and skinnier one than the reasonably standard fridge I'm used to. As someone who cooks and deliberately creates leftovers, some to be eaten that week and some I'd freeze for later, I found it *maddening*. Only one shelf with some height for taller items, little door space for the variety of condiments I keep on hand, a tiny freezer that needed 25% of the space for ice cube trays. Our farmers' market is only open weekends this time of year and I couldn't store a week's worth of vegetables with everything else already in there. Many of the ways I reduce food waste were harder, not easier.

I don't need the Kelvinator Foodarama but I need more space than that.

For years I tried to make the case that small fridges make good cities, that "people who have them are out in their community every day, buy what is seasonal and fresh, buy as much as they need, responding to the marketplace, the baker, vegetable store and neighborhood vendor."

"Responding to the marketplace."

Lloyd, it sounds like consumers are driven by "the marketplace" in your example. That's actually backward.

A successful and independent marketplace serves and is responsible to THE CONSUMERS in our capitalist driven system. When a marketplace is vibrant, it shows that producers are listening to those consumers to provide and serve them correctly.

Capitalism is all about Service. The more that one can serve the needs and wants of others, the more successful you can become.