What will the kitchen of the future be like?

It's always changing, depending on the preoccupations of the time it's envisioned.

In a 2002 essay titled “A Kitchen Manifesto,” authors Genevieve Bell and Joseph “Jofish” Kaye write that “The house of tomorrow is a vision perpetually deferred, one that tells us more about the preoccupations of the time than about the designs of the future.”

I thought of this when I was recently interviewed by a BBC researcher working on a story about the kitchen of the future. I first saw my idea of the kitchen of the future back in 2007. It wasn’t even real; it was designed for the Interior Design Show by Donald Chong and built by Derek Nicholson, delivering the message that “Small Fridges Make Good Cities.”- the idea was that you get out into your community and buy fresh food, supporting your local butcher, baker and greengrocer. It certainly nailed my preoccupations of the time; I was interviewed by a now-defunct green living magazine at the time and gave them my take on it:

“Local food, fresh ingredients, the slow food movement; these are all the rage these days. A green kitchen will have big work areas and sinks for preserving, tons of storage to keep it in, but will not have a four foot wide fridge or a six burner Viking range. It will open to outdoors to vent the heat in summer, to the rest of the house to retain the heat in winter. The dining area will be integrated into it, perhaps right in the middle. A green kitchen will be like grandma's farm kitchen- big, open, the focus of the house and no energy from the appliances will be wasted in winter or kept inside in summer.”

This was a very different vision of the kitchen of the future from the usual one, described by Rose Eveleth in a brilliant essay:

“Around the corner, in the kitchen, our lovely future wife is making dinner. She always seems to be making dinner. Because no matter how far in the future we imagine, in the kitchen, it is always the 1950’s, it is always dinnertime, and it is always the wife’s job to make it.”

This 1957 vision from General Motors (dancing in the kitchen starts at 3:20) is run by a computer and does everything, so the housewife can go play tennis, golf, and take a swim while the cake bakes itself. (There is always a cake.) The kitchen is a machine for cooking so that the woman (it’s always a woman) doesn’t have to.

The idea that women should be spared the drudgery of being stuck in the kitchen cooking was not a new one; it was one of the main principles behind the Frankfurt Kitchen designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. According to Paul Overy, it was designed “to be used quickly and efficiently to prepare meals and wash up, after which the housewife would be free to return to ... her own social, occupational or leisure pursuits."

I used to feel a bit like a poseur, writing about kitchen design when my wife Kelly did all the cooking, always very much is the Small Fridges make Good Cities mode (our freezer used to be used exclusively for martini glass storage) but then I learned that Lihotzky, perhaps the most significant kitchen designer of the century, didn’t cook either, saying “I designed the kitchen as an architect, not as a housewife.” According to the Museum of Modern Art:

Schütte- Lihotzky became convinced that “women’s struggle for economic independence and personal development meant that the rationalization of housework was an absolute necessity.” Her primary goal in the design of the Frankfurt Kitchen was to reduce the burden of women’s labor in the home…“The truth of the matter was, I’d never run a household before designing the Frankfurt Kitchen, I’d never cooked, and had no idea about cooking.”

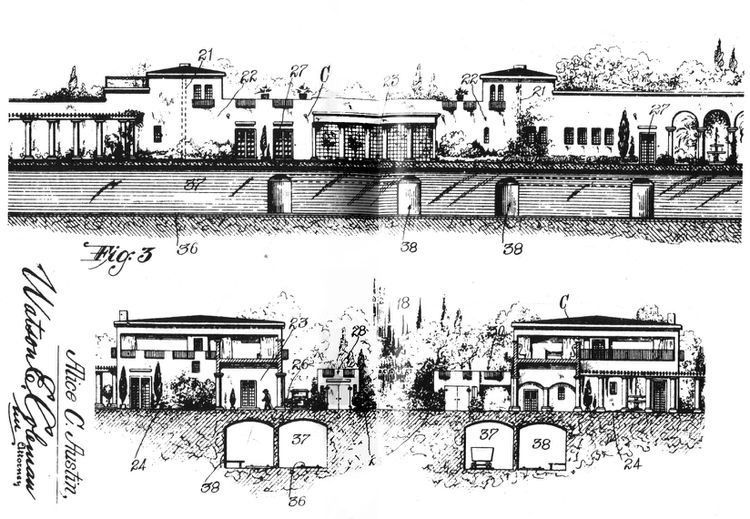

Some designers went even further and tried to get rid of the kitchen altogether. Another brilliant article by Meg Conley introduced me to Alice Constance Austin, who designed a socialist community with kitchen-less houses. “Food was to be cooked in a central kitchen and sent to communal patios by a series of underground rails. Dirty dishes sent back to the central kitchen for cleaning. Laundry would be taken care of this way too.” Again, the idea was to “free women from the drudgery of unpaid domestic work.”

The dream kitchen of the sixties is again about the preoccupation of the time, the computer which runs the kitchen. But it’s smarter; when dad says he wants a cheeseburger and fries for lunch, the computer says nope, too many calories. Two minutes later, the family sits down (on the same Thonet chairs that I have, terrible for kids!) and eats the computer-selected portion-controlled, frozen then microwaved lunch. Then the plastic dishes are melted down. Again, the motivation for all this technology is to reduce the amount of work for the housewife, who arranges flowers instead.

But this kitchen also came closest to the way the future turned out: frozen food that gets nuked. We outsourced our cooking to the frozen food section of the grocery store, the rapidly expanding ready-to-eat sections, Uber Eats, and eating out, probably in our cars. According to Roberto Ferdman in the Washington Post,

Between the mid-1960s and late 2000s, low-income households went from eating at home 95 percent of the time to only 72 percent of the time, middle-income households when from eating at home 92 percent of the time to 69 percent of the time, and high-income households went from eating at home 88 percent of the time to only 65 percent of the time.

Some, like analysts at the Swiss bank UBS, predicted in 2018 that by 2030 most meals currently cooked at home are instead ordered online and delivered from either restaurants or central kitchens, noting"The total cost of production of a professionally cooked and delivered meal could approach the cost of home-cooked food, or beat it when time is factored in." In many ways, we have seen this movie before; according to UBS,

“For skeptics, consider the analogy of sewing and clothes production. A century ago, many families in now-developed markets produced their own clothes. It was in some ways another household chore. The cost of purchasing pre-made clothes from merchants was prohibitively expensive for most, and the skills to produce clothing existed at home. Industrialisation increased production capacity, and costs fell. Supply chains were established and mass consumption followed. Some of the same characteristics are at play here: we could be at the first stage of industrialising meal production and delivery.”

Many people were appalled when the UBS report came out but I thought at the time, let’s get real; half of North America can’t even be bothered to make a cup of coffee, preferring to outsource it to their Keurig or Nespresso. If our food is prepared in large robotic kitchens and delivered by drones and droids, why would anyone need a kitchen at home, any more than they need a sewing machine?

In a Treehugger post, Why the kitchen is going the way of the sewing machine, I quoted consultant Eddie Yoon of the Harvard Business Review, who noted, cooking is being reduced to "a niche activity that a few people do only some of the time." I wrote:

Consultant Yoon claims that people fall into three groups: only 10 percent love to cook, 45 percent hate it, and 45 percent tolerate it because they have to do it. That 10 percent will always want their big kitchens. But I suspect that the other 90 percent will be a big market for delivery services, especially as the huge baby boomer cohort ages and as more and more of them live alone. For them, the kitchen is going the way of the sewing machine.

The sewing machine analogy seems particularly apt today. My daughter sews; she has a fabulous sewing room as big as her kitchen with a giant table in the middle. She doesn’t do it out of necessity; it’s a hobby.

Many house plans today, particularly for the rich, have “messy kitchens” where the Nespresso and the microwave live, and where you toast your Eggos or unpack the Uber Eats. Then there is the big hobby kitchen, (now often used by men) with the six-burner Wolf gas range, Global knives and All-Clad or Le Creuset pots.

Sewing and cooking both had a huge resurgence during the pandemic, when people had time on their hands. In 2020, according to the New York Times,

At a scale not seen in over 50 years, America is cooking ... In one recent survey, 54 percent of respondents said they cook more than before, 75 percent said they have become more confident in the kitchen, and 51 percent said they will continue to cook more after the crisis ends. Interest in online cooking tutorials, recipe websites and food blogs has surged.

Even in our house, the martini glasses had to move as Kelly couldn’t shop every day. A food consultant told the Times: “People now go to the store with purpose. The number of trips went way down, and the size of the basket went way up."

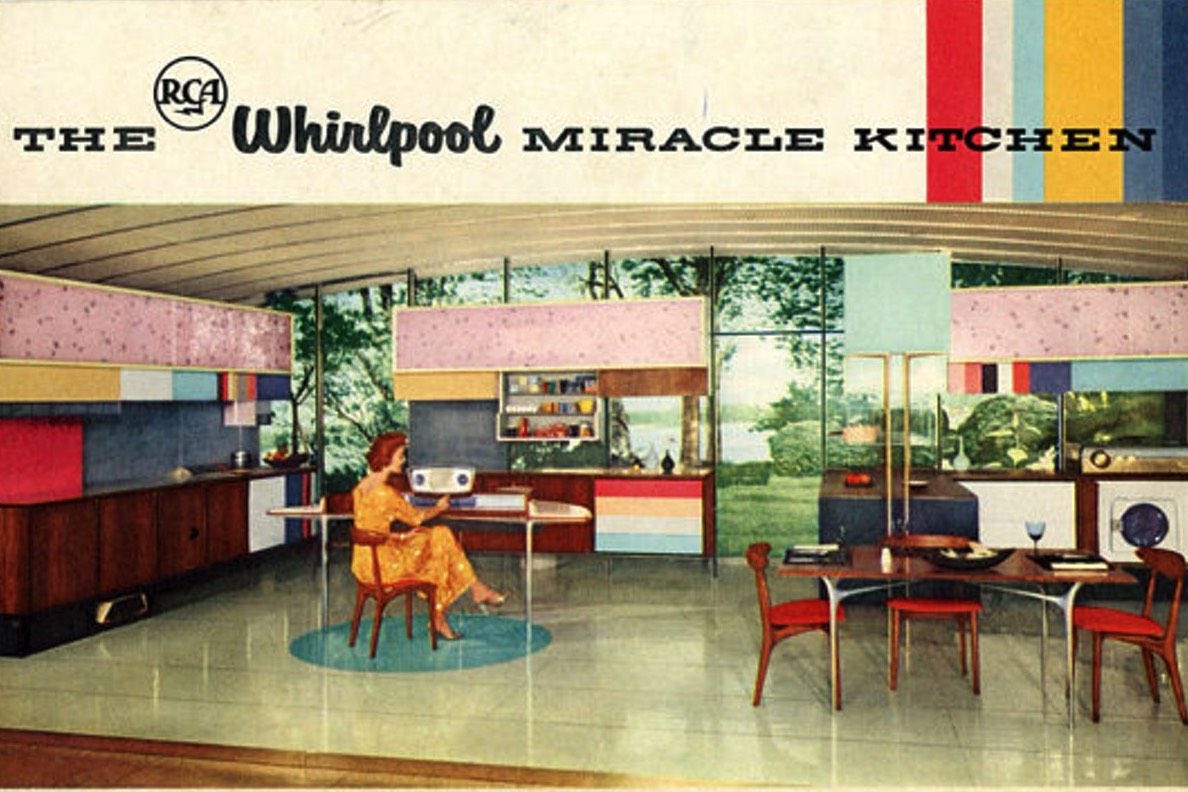

It got me thinking about the 1957 RCA Whirlpool Miracle Kitchen, big enough to live in, with all the modern conveniences. It had lots of lessons for a post-pandemic kitchen design:

Lots of storage, including refrigeration and freezing, so that one doesn't have to shop as often

Enough room for the family to participate

Easy-to-clean surfaces

Induction cooktops with lots of ventilation

Robots! Roombas! Computers! Cakes in three minutes!

It also had a feature that I think every kitchen should have today; One of the designers of the Miracle Kitchen, Joe Maxwell, was a pioneer of universal design, where the kitchen adapts to different needs. Maxwell's son Tom writes that "for the Miracle Kitchen, this meant countertops that could raise and lower and wall cabinets that lowered when opened, conforming to the user rather than building code." Even the sink moved up and down, "from tiny to typical to tall" people. The vegetable bins and bottom drawers all slid out and raised up so that nobody ever had to bend over for anything. And of course, in the video, the woman and her robot kitchen bake a cake.

But will it last, or with everyone being forced back to the office, will the kitchen disappear again?

Frederick, Austin and Schütte-Lihotzky wanted to free women from the kitchen; in the fifties and sixties, women were pushed back into the kitchen to raise the baby boomers; today, many people work long hours and live in tiny apartments. Maybe women shouldn’t have to do cook if they don’t want to?

As Kay and Bell noted, the kitchen of the future reflects the preoccupations of our time. I wrote previously that “kitchen design, like every other kind of design, is not just about how things look; it is political. It is social. In kitchen design, it is all about the role of women in society.”

Being a man who doesn’t cook much, I should probably have stayed out of this, but I still wonder if the kitchen of the future really is no kitchen at all.

Or maybe it will be like Philipe Starck’s vision for Warendorf. There’s not much to it, some rotating cabinets and a floating island with sink and stove. It is efficient and open, and leaves lots of room for a woman in evening wear to use her jackhammer on big chunks of glass. This could be the future we want.

Clothes are cheap because they're made in low income countries. I don't see meals being prepared thousands of miles away and shipped to me. And of courses meal delivery is about as ungreen as imaginable. Somebody has to cook it. Then wrap it in something that will keep it cold, hot, frozen or fresh. Then somebody has to deliver it. The recipient unpacks it, tosses the huge volume of probably not recyclable packaging, then gets to eat it. Cost is double, triple or ?.

Living in rural Maine, one either cooks or eats crap. Tonight is pizza night at my house. I made the dough yesterday, enough for three pizzas. Froze two pies worth. Tonight, we'll thinly slice potato and sweet potato on a mandoline, slather on some chimichuri sauce and caramelized onion, top with my wife's homemade vegan cheese. Wash it down with a local beer.

Anyone can cook and everyone should know how. It's fun, cheap and healthy.

I built our kitchen, based on our experience in other kitchens. It's not too big, but has plenty of storage, including a tiny pantry. Oven is a few feet above the floor, which I highly recommend. Under the counter, drawers, not doors and shelves, work better. No extravagant appliances. It's a working kitchen, not a showy one.

We now live in a lively and well appointed small town in rural France, with quite good access to local food (baker, weekly market and fish van) I volunteer at the community garden and get stacks of (dirty, cumbersome) fresh veg, and we grow a bit more, we are retired, have time to shop locally and cook almost entirely from scratch. I am the female and cook more, mostly because I like it and my husband pulls his weight in other ways which suit him better, but he cooks too, and we shop and stock take and plan meals together. We are both committed to living sustainably and with the minimum of waste. Consequently, we need quite a lot of fridge and freezer space for leftovers and extra portions (to avoid wasting food or energy), stocking bags of muddy fresh veg and conserving gluts of produce. We tried at first to live with one small fridge and freezer, it didn't work.