Will circadian lighting take us back to offices without windows?

We are going to have to figure out what is most important: energy efficiency, upfront carbon, or a view of the sky and the flash of a sunbeam.

Back in the 1970s and 80s, North American office buildings often had vast floor plates, and people often worked all day without access to windows. I thought these were awful and often pointed to the German building regulations as a model to emulate; their buildings tend to be skinny because every employee has to have access to a window with a view of the sky and natural ventilation.

Over the last twenty years, we have learned about the importance of circadian rhythms and how the colour of natural light changes throughout the day. Access to windows has become even more critical for our health and well-being. I like to quote daylighting designer Debra Burnet: “Daylight is a drug, and nature is the dispensing physician.”

This is a subject we covered before, most recently in Low-E coatings on windows save energy, but may be messing with our health, and I have wondered whether circadian LED lighting could do the job. Ray Smith of the Wall Street Journal looks at the issue:

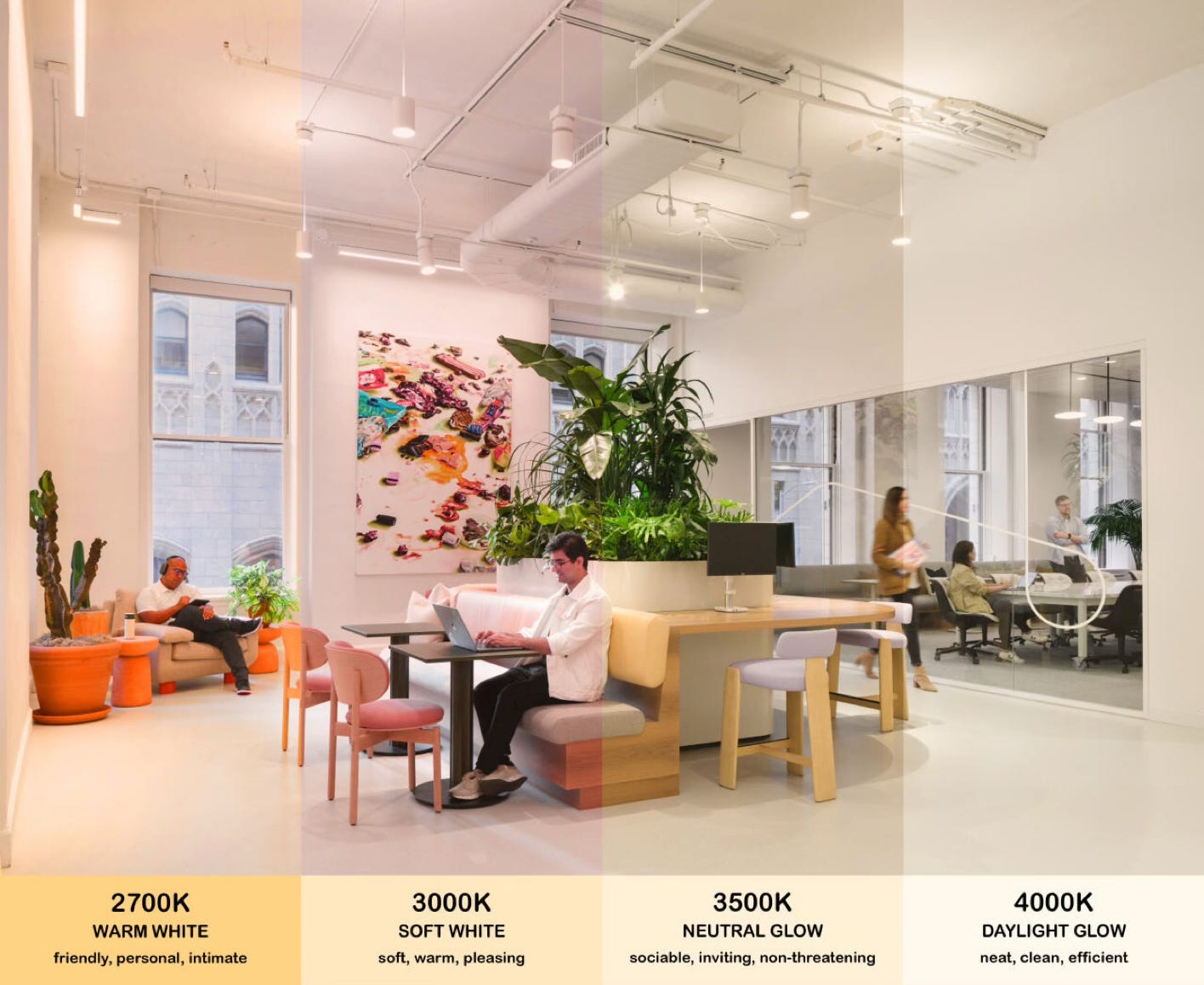

Improved, and potentially more healthful, lighting is high on the list for companies and building owners trying to lure employees back to offices after an era of remote work. They are investing in new technologies such as faux skylights that mimic natural light—complete with a virtual sun and moon—and adjustable illumination systems designed to sync with employees’ circadian rhythms.

The Journal shows us lighting products from Innerscene, which include “Circadian Sky and Virtual Sun.”

“The windows and skylights are intended for office spaces with little natural lighting. Floors in multistory-buildings that otherwise wouldn’t be able to have skylights, or where light is blocked by nearby skyscrapers are also potential uses… In March, Innerscene announced its next product: sensors that sample the color and intensity of the sky and wirelessly transmit that data into the artificial windows and skylights to show the same view.”

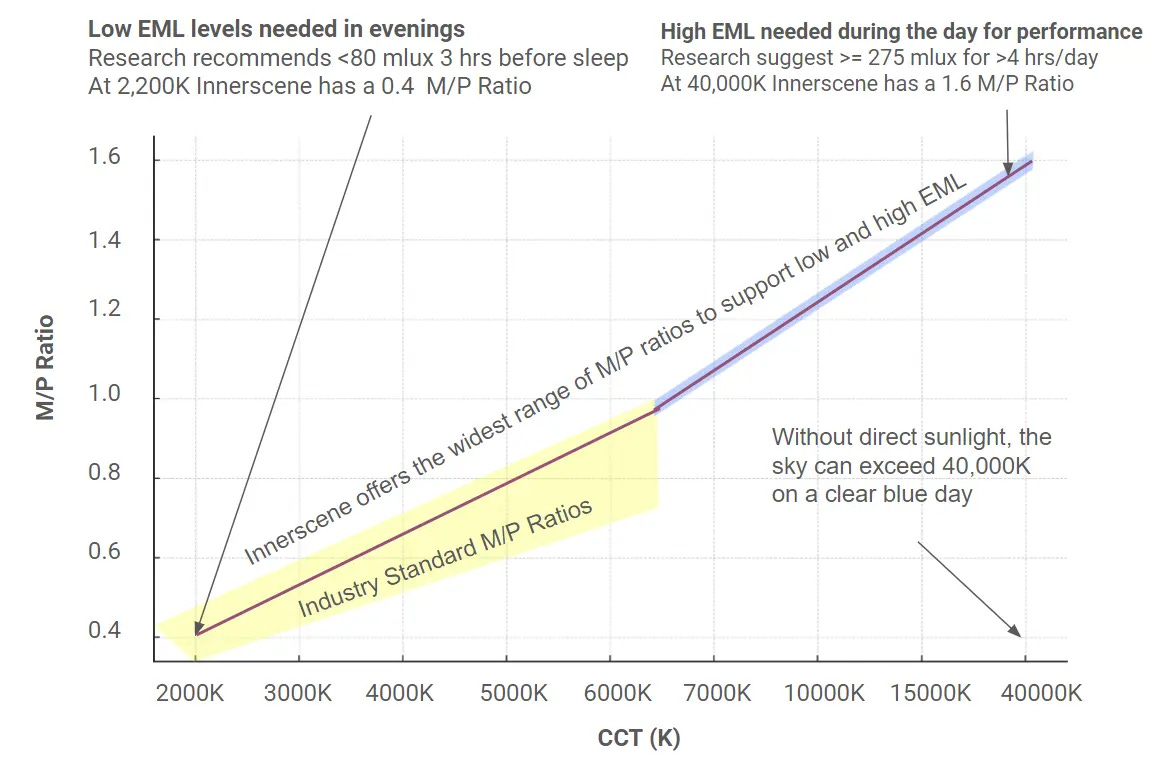

The Innerscene website includes extensive research discussing “ipRGCs (Intrinsically Photosensitive Retinal Ganglion Cells). ipRGCs are a type of retinal ganglion cell that are intrinsically photosensitive. They are involved in the pupillary light reflex and circadian photoentrainment.”

However, when I scroll through the gallery of Innerscene installations, I worry that we may find ourselves returning to the era of windowless offices and classrooms, which were common when windows were thought of as a distraction or a waste of energy.

Buildings with lots of windows and surface area, like my German model, are lovely. Still, I recently attended a Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH) virtual seminar on upfront carbon in tall buildings, demonstrating that simple form factors and boxy buildings have the lowest upfront carbon per unit of floor area.

Then there is my favourite study, What really matters in multi-storey building design? A simultaneous sensitivity study of embodied carbon, construction cost, and operational energy, where Hannes Gauch and his team built a magic box of a conceptual building with input variables for a building's shape, size, layout, structure, ventilation, windows, insulation, air, and use for residential and office multi-story buildings, across different climates. What we end up with are short, boxy buildings with not very high window-to-wall ratios.

I took many photos of that building next to the Reichstag in Berlin in 2017, thinking it was a great demonstration of how to give employees light and air. Today, I wonder, with mechanical ventilation and circadian lighting, how do we find a balance between building form, energy efficiency, window size, number of layers of glass, coatings, and upfront carbon? Do we need windows at all? I asked engineer Nick Grant about this a few years ago, and he responded,

"Despite my banging on about efficiency and sufficiency, I’m partial to the odd window placed for a Zen view or mid-winter sunbeam that does nothing for heating or daylight but lifts the spirits."

I am not sure that circadian lighting can do that yet.

Second-last in my series of posts on windows, I promise. Previously:

Low-E coatings on windows save energy but may be messing with our health. The coatings let visible light in but reduce wavelengths of light that we need for our health.

Looking at windows: excerpts from The New Manual. In which I go from small windows to thinking big.

Special Offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$34.95 )

These artificial lighting solutions are great for retrofits, but I hope people won’t make the mistake of maximizing energy efficiency at the cost of human experience. It’s not that difficult to optimize between the two. I’m not a slab of venison. Don’t expect me to work inside a chest freezer.

I'm really enjoying this windows series, Lloyd. It's true there are no simple answers or formulae, our relation to windows - etymologically derived from 'eye' and 'wind' - to light and vision and air, and also our need for enclosure and darkness, are very subjective, cultural and intuitive, yet I think we're not really fully attuned to or aware enough of this.

We went from living in an old stone Breton house with walls a metre thick, with interesting, dynamic if restricted lighting, to a new-build on a small lotissement (private housing estate) built by a local wooden house specialist, which I consider to be boxy but beautiful, with quite a lot of window area. We love the interior luminosity, and the fact that in hot weather we can open the windows and French doors and get enough through-draught to stay cool (and wasps, hornets and flies come and go freely), almost like living in a rigid tent! Other than the French doors, most of the windows are quite large but relatively high, which enables better ventilation and also privacy, so we get plenty of light, views of sky and trees but aren't overlooked. Double glazing, outside roller blinds and inside roman and strip blinds (the latter with heat reflective coating) keep us warm enough in winter, in a fairly mild maritime northern European climate. A mosquito net panel means we can keep the bedroom window wide open all night in summer.

So we're pretty happy with things, yet we didn't really discuss windows with the builder in depth, and we've had to use quite a lot of trial and error and add-ons to find comfortable solutions. The plate glass French doors give a nice view onto the garden in a sheltered SW facing angle, but that aspect and the terrace adjacent to it get uncomfortably hot quite quickly, and we can't close the strip blind and maintain the through draught at the same time. A pergola built on the terrace has helped a bit, as has planting more shrubs and trees round the house. The light is lovely most of the year, yet we miss the lost wall space for art and bookshelves, and the deep window sills for growing plants (although in European houses, where windows always open inwards because of shutters, sills are not very usable). Likewise, I love the lightness and flexibility of our wooden house (and the cleaner indoor air from the controlled ventilation system) but miss the coolth of thick stone walls and tiled floors in the ever more frequent heat waves. I'm not very fond of cleaning windows either!