Why we need frugal design and innovation

Frugal green living is hard, but there is no reason we can't have nice things that are robust, simple, repairable and essentially frugal.

Author Michelle Teheux of Untrickled describes herself as “a selectively frugal non-conformist” in a post titled Modern Conveniences, Selectively Declined. She doesn’t have streaming services, rarely uses her dryer, but, like me, she does have a microwave, a bidet (see Why everyone should have a bidet toilet seat) and the same Breville espresso coffee maker that I have (although hers is much shinier). I can attest that anyone who has a bidet and a Breville is indeed being very selective about their frugality.

I often compare my Breville, which costs about $800 and weighs about 22 pounds, to a French press coffee maker, $12.95 at IKEA and weighing about 10 ounces. They both do sort of the same thing (make coffee), but provide a great demonstration of:

Simplicity. The French Press does the job with one moving part, no motors or pumps or circuit boards, you just press.

Sufficiency. How much is enough coffee maker? How much do you really need? And, of course,

Frugality. Seriously, the French Press costs 1/61th of the espresso machine.

All three of these words are chapters in my book The Story of Upfront Carbon, but I want to concentrate here on Teheux’s description of herself as “selectively frugal.” Besides her Breville and her bidet, her third item in her list of modern conveniences was an electric grain mill, purchased after calculating that baking her own bread was one of her most extreme money-saving measures. “If I could figure out a way to grow my own wheat in my yard, you bet your baguette I would.”

I thought that an interesting statement; in his book The Wisdom of Frugality: Why less is more- more or less, Emrys Westacott notes that baking one’s own bread has become a symbol of wholesomeness and self-sufficiency, but as Joe Pinsker summarized,

“It’s hardly an act of pure independence. Since most home bakers are not growing their own wheat, grinding their own flour, constructing their own ovens, and so on, they are aided by labor-saving technologies that are miraculous and yet commonplace. It’s perfectly valid to bake bread because it’s cheaper, fresher, and less connected to processed-food supply chains, he suggests, but don’t get carried away: Baking bread at home is the result of the remarkable interconnectedness of the modern economy.”

Joe Pinsker was the author of a wonderful article in the Atlantic a decade ago, Frugality Isn’t What It Used to Be. He notes that it is much easier to be selectively frugal if you have time and money.

“Living a pared-down lifestyle necessarily means having a lifestyle to pare down. More often than not, the decision to live frugally is one made by people who can afford to opt out of a well-paid, well-spent lifestyle they have already secured.”

Indeed, I can choose not to drive because I live in a wealthy part of town and can get everything within walking or biking distance. At least half a dozen big espresso machines are being pumped by expert baristas within a ten-minute walk of my house; I don’t really need my own.

My wife, Kelly, spends a week over a hot stove every August canning tomatoes, but it’s hardly frugal, when you total up the tomatoes, the jars which each cost almost as much as a tin of tomatoes in the store, and the space to store them all. And of course, the most expensive part of the exercise: the time.

However, there is another aspect of frugality that I ascribe to, and suspect Michelle Teheux does as well, based on her description of her old clothes dryer. This is what has been called frugal design. It would benefit everyone, and especially those without time or money.

Remember the window crank? My first car, a 1965 VW Beetle, had a manually cranked window. My mother’s 2000 Toyota Echo, which just finally died a few years ago, had window cranks. Now, even the cheapest cars have switches, electric motors and wiring, adding weight, complexity and cost, just so you can press a button instead of turning a crank. The Echo had a little lever which adjusted the side mirror; my daughter’s car has electric controls. I backed her car out of the driveway and knocked the driver’s side mirror off; replacing it cost $500.

What have we gained here? Why does everything get more complicated? Why is everything so expensive to repair, if it can be repaired at all?

Alas, it turns out that most people want convenience, they like switches instead of cranks, and they want more. They don’t look at the world through the lens of frugality.

I wrote about this in my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon; here is the section on Frugal Design.

Benjamin Franklin defined frugality as a virtue: “Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; that is, waste nothing.” A dictionary definition is “the tendency to acquire goods and services in a restrained manner, and resourceful use of already owned economic goods and services.” Frugality often comes up in discussions of personal finance, with recommendations that one skip the latte or the avocado toast.

But there is another use of the term frugality that is more relevant to the question of the design and manufacture of stuff. It is called frugal design, frugal innovation, or frugal engineering, a term used by Carlos Ghosn of Nissan Renault before he was frugally carried out of Japan in a suitcase, who noted in 2006: “Frugal engineering is achieving more with fewer resources.” Ghosn learned about it in India, where it has been practiced for decades in the design of everything.

It’s not just about being cheap, although cost is a big part of it; there are other attributes that make frugal design attractive to anyone.

Robustness. India has a harsh environment with extremes of temperature, erratic electricity supply, and dust.

Portability. It’s a big country with lousy transportation links, so you want small products that are easy to carry.

Defeaturing. This is one of the most interesting attributes. According to an article in the Ivy Business Journal, “Defeaturing consists of feature rationalization, or ’ditching the junk DNA’ that tends to accumulate in products over time. With Indian consumers, firms can avoid implementing features that do little to enhance the actual product.“

Service Ecosystems. Today, it is easy to see a plethora of small repair shops and other businesses that have mushroomed around population centres in India. The use of these service ecosystems—which comprise not just parts and repair but financing as well—can help firms enlarge their product markets.” The products are designed for serviceability because that is what the customer expects. In North America, the customer may expect it, but good luck getting it; I have spent considerably more on getting service on our clothes washer than I paid for it in the first place.

Ghosn applied the principles of frugal engineering and the mantra “do more with less” to produce low-cost vehicles that became hugely popular in Europe and Asia. And while Ghosn’s career ended in ignominy, frugal engineering and innovation remain popular, with organizations such as Finland’s Innofrugal promoting “the creation of sustainable economic growth via co-creating good quality, accessible, affordable, and sustainable solutions.”

Frugal design—doing more with less—makes sense in these times. Frugal engineer Balkrishna C. Rao says, “Frugal engineering is an important tool for tackling the challenges thrown by climate change and other planetary and manmade crises of our time. Frugal engineering is significant for all-round sustainable development.”

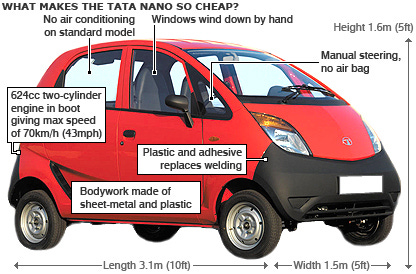

Frugal engineering started with cars, but it can be applied to anything; the other product that all the articles from a decade ago talk about is the ChotuKool refrigerator, a small fridge that cooled with a chip instead of a compressor. It and the Tata Nano, the first car designed from the ground up around frugal engineering principles, flopped in the market. According to Knowledge at Wharton, “aspirations matter.”

Analysis showed that the “world’s cheapest car” wasn’t really an attractive positioning for what would have been an aspirational purchase for first-time car owners. The fridge failed because, as one of the senior executives responsible for ChotuKool noted: “We realized that the aspirations of the lower income people come from the richer people, and unless the rich buy, the lower income segment won’t.”

A decade ago, I wrote about both products, thinking the Nano was the right size for urban driving, and that “small fridges make good cities.” This reinforces Joe Pinsker’s point about frugality being a choice made by people like me who already have money and can walk to the neighbourhood shop for milk and don’t need to drive to Walmart. Others need or aspire to bigger cars and bigger fridges.

Aspirations do matter, which is one of the problems in dealing with the climate crisis, but it doesn’t negate the value of frugal engineering.

Special offer!

I do not want to put up a paywall on this site, but it provides a meaningful portion of my income. So here’s a limited-time offer: I will send a signed copy of the print edition of “Living the 1.5 Lifestyle” to anyone in the USA or Canada who signs up for a one-year subscription (C$50, cheap at about US$35 ).

Your examples also demonstrate the risks around this design philosophy.

The risk is in that reducing everything to its minimum functionality, You will reduce too much of the functionality to a level in which the target customers no longer regard as adequate.

In the case of your coffee plunger (which is what I used to make the coffee that is on the desk in front of me) the resulting coffee does indeed taste different from an espresso machine. Additionally, of course it does not froth the milk. So if your objective is a nice fluffy latte or cappuccino. Then the coffee plunger fails in it objective.

In the case of the Tata Nano it both cost more to manufacture than the designers expected, and it's functionality was so minimalist that it was less than what the market wanted.

For only about 10% more on the purchase price the market already had available a considerably better car which sold consequently in large numbers.

Another example of this will be a computer system from my youth. There was a computer called the BBC micro, manufactured by a company called acorn. They had the great idea of doing a minimalist version of it called the electron which would be cheaper to produce use fewer materials and be cheaper to buy. But again they drop the functionality below what the market wanted, sales were so poor that it bankrupted at the company.

In the case of your door opener there's a slightly counterintuitive reason for what happened there. Givin advanced production techniques and technologies used by the manufacturer, the power door openers are cheaper to make and install than the old-fashioned manual handle and wire versions.

The feature list is another risky area for manufacturers, because many consumers played the "tick box" game where they will buy a product which has the maximum amount of boxes ticked on the marketing material displayed on its front rather than carefully considering it's functionality.

In such a market, your frugality and minimalist approach will fail you.

French Press coffee, because it doesn't go through a paper filter, is not good for your heart. Gemini: "while French press coffee offers a rich flavor, its lack of a paper filter allows diterpenes like cafestol and kahweol to remain in the brew, which can lead to increased LDL cholesterol levels, particularly with high consumption."

Sadly Gemini says espresso too: "Research suggests that espresso has an intermediate content of cafestol and kahweol compared to other brewing methods."

I am sorry about this.