Why fighting small apartment buildings is self-defeating and short-sighted

People may not want neighbourhood change, but they can't avoid their own needs changing.

In Toronto where I live, there is a fight going on about rezoning what they call “major” streets to permit townhouses and rental buildings six storeys high. A city councillor complains that people won’t like it.

“These are people that have worked all of their lives to pay the bills, to pay rent, to live in the neighbourhoods that they dreamed and aspired to live in. And why should they accept change? Why should they accept change at this pace?”

The problem is that while they may not want their neighbourhood to change, they themselves are changing as they age. Their needs are going to change. They are most likely baby boomers and the kind of housing that they are fighting is exactly the kind of housing that they are going to want or need in a few years.

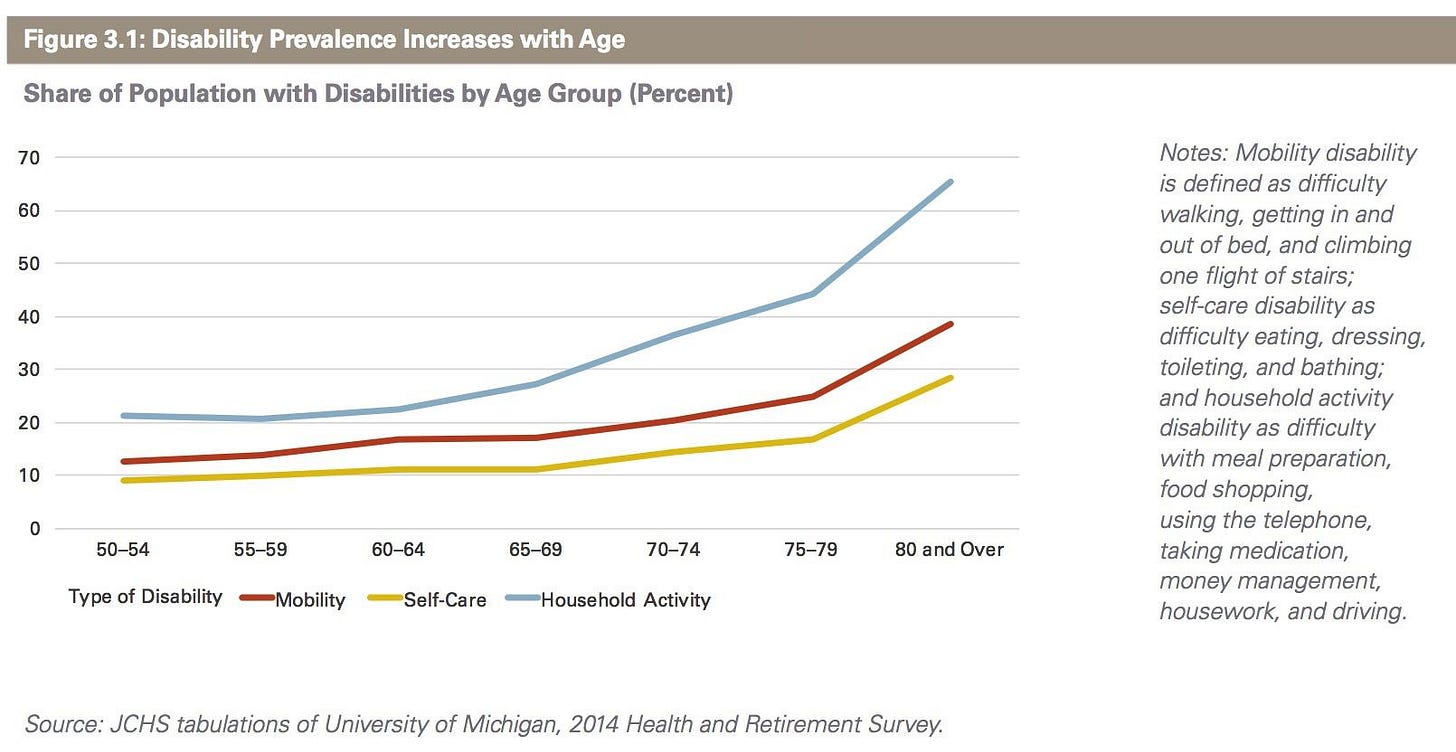

In the US, according to the census, significant numbers of people have difficulty doing some pretty ordinary things, as basic as getting into their homes. 39% of households have at least one person with a disability or being over 65 (hardly a disability), but likely means that disabilities are coming soon.

There are 70 million baby boomers in North America who are now part of the “young-old” and can drive, climb stairs, and show up at public meetings to fight change. But in ten years, many will be part of the “old-old” who have trouble with household activities like driving or shopping.

Some real estate developers get this; this is a 70 unit “active adult” building in Northhampton, Mass built of mass timber to Passive House standards, which I wrote about on Treehugger. the developer notes, "the average man outlives his ability to drive by 7 years, the average woman by 10 years" and "walkable neighborhoods can be mobility enabling and health enhancing for millions." It’s not a retirement home, but nice rental apartments where people can live without a car.

"With a mission to 'transform how older Americans live, with new buildings in walkable, connected communities,' Live Give Play has conceived a residential concept that supports healthy lifestyles (Live), community service (Give), and cultural engagement (Play) — all offered in an environmentally progressive structure and with attainable rents."

Down the road from Toronto in Oakville, Ontario, the city council just voted 14-1 to reject upzoning to allow four-storey buildings as part of a federal program to build “gentle density” housing; according to the Star, “after local residents expressed concerns the policies would change the character of established neighbourhoods.”

“We don’t need to risk our neighbourhoods livability for the small amount in the housing accelerator fund grant,” said [Mayor] Burton at the council meeting where he brought in the motion to reject the gentle density policies. “Thanks to our financial strength, we don’t have to accept a bad deal.”

And where are thse people going to live in ten years? Unlike these American sprawly houses, Oakville homes don’t have only one floor, don’t have full baths and bedrooms on the first floor, or have step-free entryways. Wouldn’t it be nice if they could stay in their own neighbourhood as they age, close to everything and everyone that they know? This is the kind of change people should be fighting, being forced to move far away because there is no suitable apartment accommodation nearby.

In a 2019 study, Neighborhood Defenders and the Capture of Land Use Politics Katherine Levine Einstein, David M. Glick, and Maxwell B. Palmerd discussed the politics of housing. Their research was in Massachusetts, but seems to apply to Toronto too:

Land use regulations can directly forbid the construction of high-density development and restrict the supply of housing. But, they may also reduce housing production by creating a political process that amplifies the voices of housing opponents. Land use regulations create opportunities for members of the public to have a say in the housing development process. Many types of housing proposals require public hearings which solicit input from neighborhood residents. This is by design. After the excesses of urban renewal, many localities turned to neighborhood-oriented processes as a check against developer dominance. But, like many participatory institutions, these land use forums may be vulnerable to capture by advantaged neighborhood residents eager to preserve home values, exclusive access to public goods, and community character.

And guess what?

We find that only 15 percent of meeting participants show up in support of the construction of new housing. Sixty-three percent oppose new development projects. Meeting commenters are also starkly unrepresentative of the mass public. Relative to Massachusetts voters, they are 25 percentage points more likely to be homeowners. They are also significantly older, more likely to be longtime residents, and male. They are nine percentage points more likely to be white.

I have been impressed that Toronto politicians are mostly supportive of more housing on major streets, and that the federal government has been promoting more “gentle density.” But it’s always a fight, it always takes years, and there are always expensive compromises. And it appears that the people who fight change are hardest are likely the ones that are going to need change the most.

In ten years, those old white men are likely going to look back and wish that building they fought had actually been built.

I'm sure you are partly right about people being blind to their future needs.

But I think there is another factor - high density housing in the US is butt-ugly and demoralizing. Traditional zoning makes it hard to change, and developer profit incentives mean housing will be as plain and highly standardized as possible. The idea of losing a view or open space so another developer can make another few million and your community ends with an another ugly box is just depressing.

I'd love to see what architects could come up with when charged with designing dense, green housing that provides both privacy and inviting public space, preferably within a small food forest. I remember reading about a development (although not extremely dense) like this in Northern California - it looked amazing.

Here in San Diego, they have changed zoning to allow for semi-high rise apartments and condos in commercially zones areas, and the changes have been profound. The sky scape of some places has drastically changed. This is all happening in areas that should have allowed for this years, perhaps decades ago. Although I don't like all the architecture, some of which is just plain unattractive, I appreciate the newness and the dynamic that is going on.