Why everyone should care about upfront carbon (and why I wrote a book about it)

My new book may be about upfront carbon, but it's not just about buildings, and it's not just for building professionals.

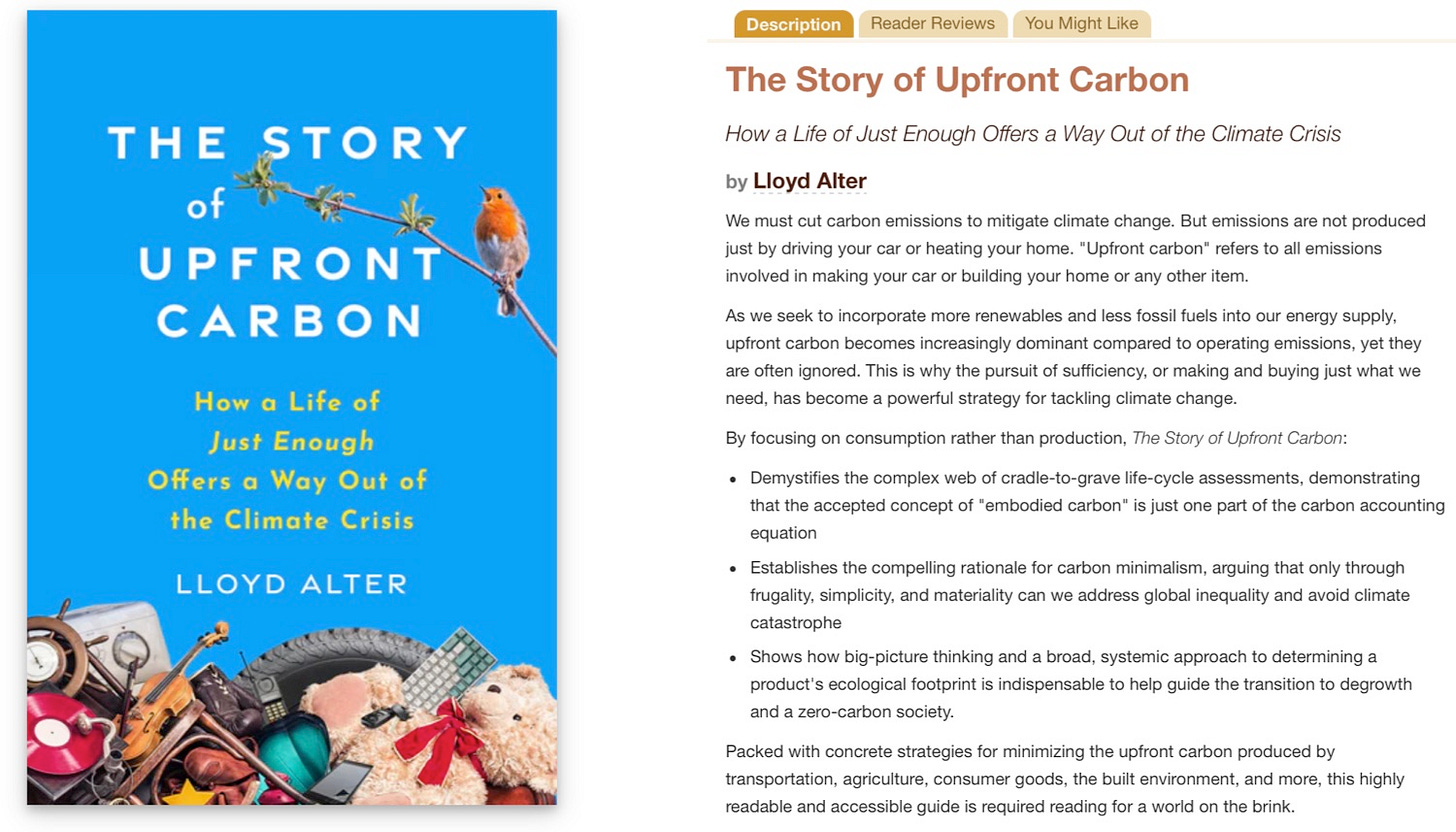

On my recent trip to Europe, many architects and engineers told me they looked forward to reading my new book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, which will be released by New Society Publishers in North America on May 21.

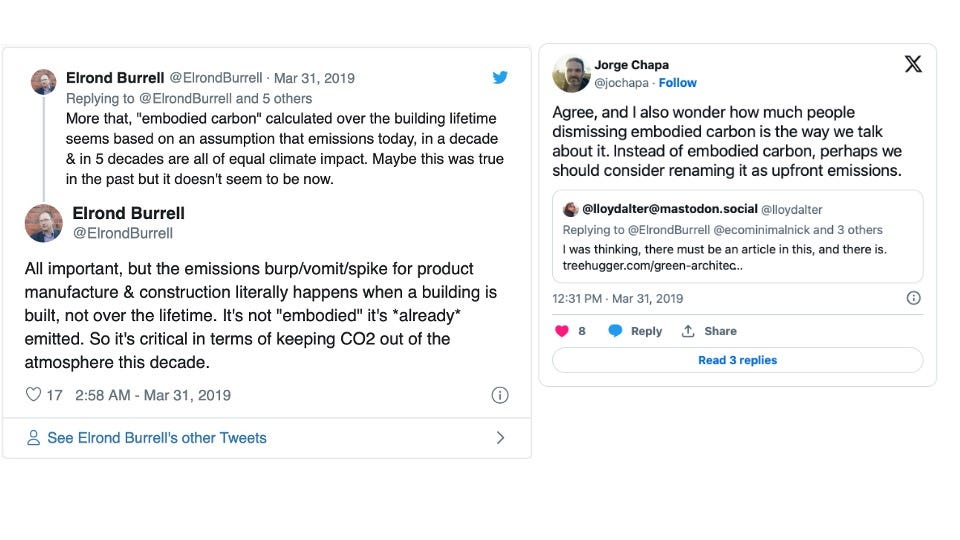

This excited me but made me very nervous because I didn’t write the book for building professionals. Most of them know what embodied carbon is and know how to measure it. They have libraries of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) telling them how much is in the materials they choose. But architects and engineers live in their own bubbles and speak their own languages. They are even perfectly happy with the silly and confusing name “embodied carbon,” even though they know it isn’t embodied at all.

But forget the bubble; the world isn’t just made of buildings. According to Architecture 2030, buildings account for 39% of emissions. That leaves another 61%, and it is all made of stuff, too, stuff that’s dug out of the ground. Stuff that’s manufactured from petrochemicals. Stuff that is grown and turned into cows and geese, which is why I talk about hamburgers and puffer jackets, as well as some building stuff like 2x4s and foam insulation.

I wrote this book so that readers would understand that there are upfront carbon emissions from making everything, everywhere, they are huge, and they are happening now. That’s why I started with my iPhone 11 Pro, an object that weighs 6.63 ounces but has upfront carbon emissions of 176 pounds. Everyone has held a phone, and I want them to imagine how much it weighs in carbon emissions, almost all of which come from making it.

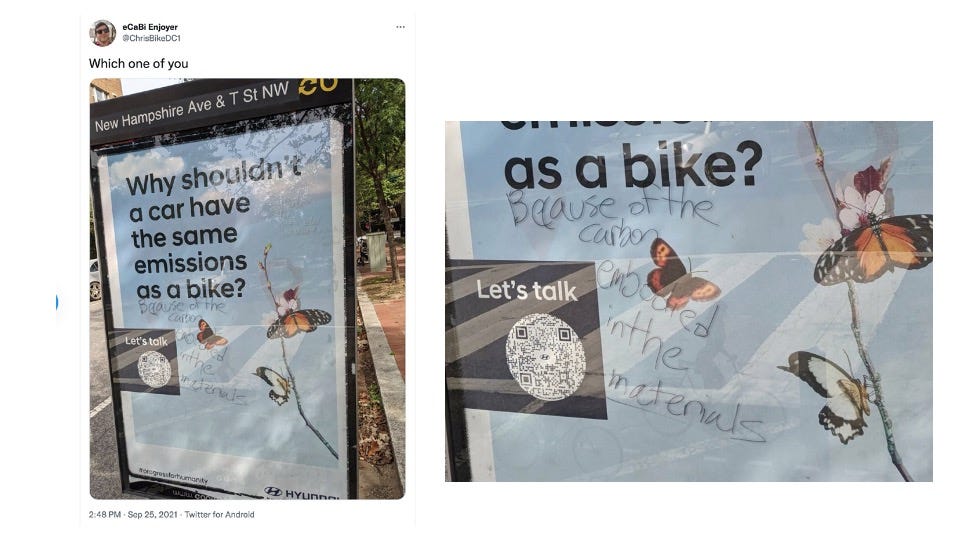

I want readers to be like the graffiti guy here who understands the difference between a car and a bicycle, “the carbon embodied in the materials,” even if Hyundai doesn’t.

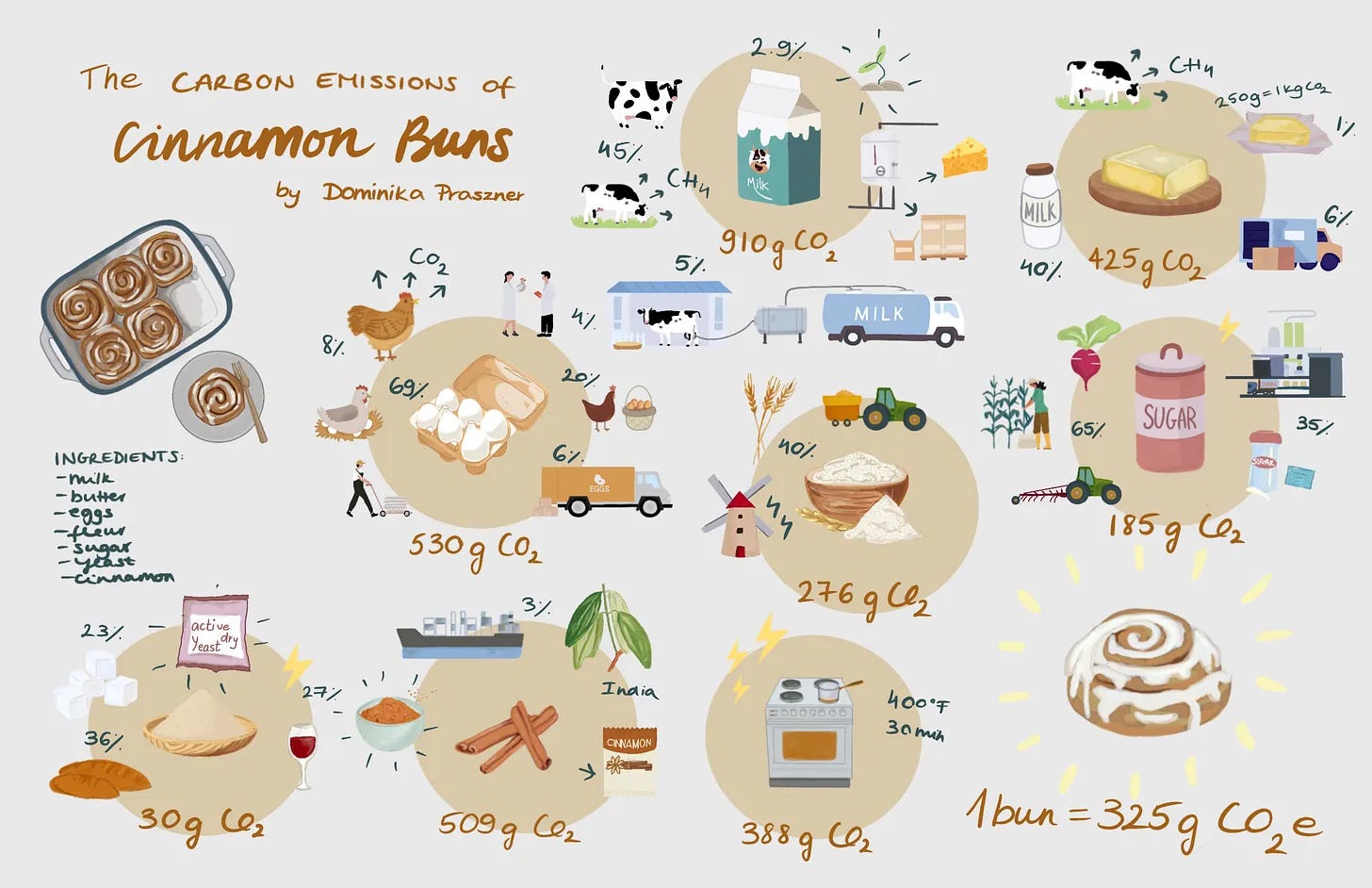

It’s why my design students at Toronto Metropolitan University had to figure out the upfront carbon in everything from gold chains to ballpoint pens to cinnamon buns; it’s not just buildings; it’s what’s in them and around them. It’s part of our lives.

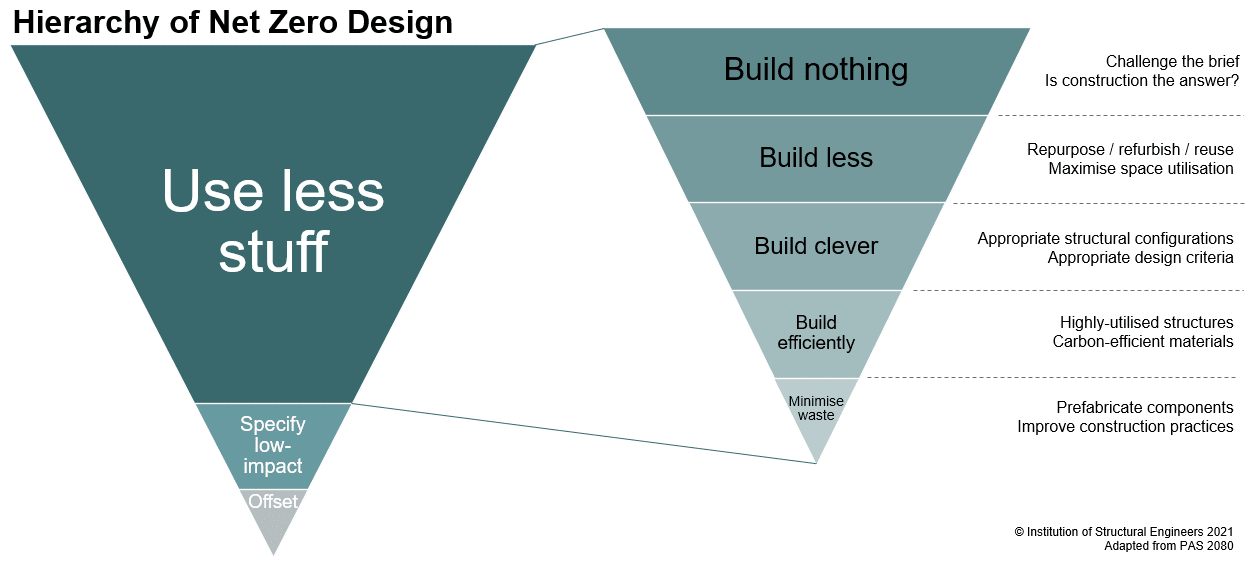

I want readers to understand that although Will Arnold’s “Use less stuff” mantra was for the building industry, it applies to everything and everyone. I should have made my own inverted pyramid with buy nothing, repair and repurpose, buy clever, and buy efficient; it all ends up in “use less stuff.”

In the end, I want readers to get that it’s all about sufficiency, as the subhead says: “How a life of just enough offers a way out of the climate crisis.” Designers might like my strategies for sufficiency, which include frugality, ephemerality, simplicity, and more. But these also work for everyone in everyday life.

I want readers to understand that everything connects. It’s not like you can actually separate buildings from transportation, which is mostly driving between buildings, or industry, which is making the cars or the stuff we fill our buildings with; it’s all built environment. In the book, I claim that built environment emissions total 75% of carbon emissions, with the balance for food and agriculture. If I were writing it now, I would make it even higher since much of agriculture is about land use, much of its emissions come from making red meat, and much of our built environment is devoted to serving hamburgers.

But I remain nervous because I am not sure if people will get this. Outside of the building industry, not many people have heard of upfront carbon, which is not surprising since the term was invented five years ago in a Twitter chat among three architects. It doesn’t even have general acceptance in the industry, let alone the rest of the world.

I feel better having great blurbs from the likes of Denis Hayes, Barnabas Calder, Kaid Benfield, and Bart Hawkins Kreps. I don’t think they were just being polite. And my wife, voracious reader Kelly, says it’s a good book, better than my last. That means a lot!

I hope it finds its audience. I was discussing this with Hattie Hartman of the Architects Journal and suggested that “it’s not for architects, it’s for their clients.” Perhaps they will both find it interesting and useful.

Already preordered

Has anyone calculated the point during climate change at which it is simply no longer possible to carry on as we have and must seriously change over globally to make it last, make it do, do without lifestyles? Probably not because there will not be a single point in time marking the before and the after but a gradual process of change and increasing limitations until we suddenly tip into the new world.