Why do open kitchens feel so wrong?

The way we eat has changed; kitchen design should too. The modern kitchen should be small, efficient, and closed.

Matt Power, editor-in-chief of Green Builder, complains about closed kitchen designs in an article titled Why Do Outdated Kitchens Feel So Wrong? He claims they are “designed for an earlier time when servants were common and women had few freedoms, old kitchens remind us of a culture most of us don’t want to revisit.” Surprisingly, for a green builder, he calls for ripping them out, concluding:

“A modern kitchen is open to the rest of the home. It connects food preparation with daily life. It allows parents to commune with kids, provides a space for serious conversations and education of family members, and a place to chat with guests as food is shared. It’s also a “statement” about who calls the shots in the family hierarchy. For most of us, decisions are shared, as are our chores and household “duties,” not dictated to our spouse or partner. Our kitchens should reflect that.”

I have been writing about kitchens for years on Treehugger, my Substack and for my next book, The New Manual of the Dwelling. I want to apologize to Power in advance for piling on his every word; his article gave me a serious incentive to pull my thoughts together. I disagree with much of what Power writes, from the history of the old kitchens to the ideas for the new ones. I even take issue with his AI vision of kitchen hell, which I rather like. He complains about women being trapped in the kitchen and then proposes turning the entire house into a kitchen.

I also apologize to my readers for my longest post ever, and for using footnotes instead of links, because that is what my Scrivener book software is set up to do.

I should preface my writing here with my counterpoint: I believe the open kitchen should die. In many homes it is already dead, a vast parking lot of giant underutilized appliances. People in the US and Canada now eat home-cooked meals only 8.2 times per week1. 57% of meals are eaten alone2. Yet fridge doors are opened an average of 50 times a day; we are not dining but grazing. Eddie Yoon of the Harvard Business Review found that only 10% of consumers love to cook, 45% hate it, and 45% are lukewarm but tolerate it and do it because they have to. He believes cooking is changing, noting,3

“I’ve come to think of cooking as being similar to sewing. As recently as the early 20th century, many people sewed their own clothing. Today, the vast majority of Americans buy clothing made by someone else; the tiny minority who still buy fabric and raw materials do it mainly as a hobby.”

This is the logical conclusion of changes in the kitchen going back to Catherine Beecher in 1869. Since then, She and almost every other kitchen expert (almost all of whom are women, many of whom didn’t cook) have had one goal: to reduce the time women spend in the kitchen. And what do our modern kitchens do? They ensure the woman never leaves it.

Open kitchens used to be the standard; everyone lived in them. That is where the heat and the water were, not to mention the chairs and tables. Families often worked in the kitchen, as this family is, making garters in a New York tenement.

Power writes that kitchens were “designed for an earlier time, when servants were common.” They were not; Charlotte Perkins Gilman wrote in 1917 in The Housekeeper and the Food Problem, “In our country, it has been estimated that only one woman in sixteen keeps even one servant. In the great majority of cases the wife and mother is also the domestic servant.” Women were trapped in servitude.

Like Eddie Yoon, Gilman thought cooking was archaic and outdated, noting that cooking wasn’t just following sewing but just about everything that used to be done in the house.

“It should be recognized that the preparation of food is no longer a domestic industry. It is no more an integral part of home life than is the making of cloth, once so exclusively feminine and domestic that the unmarried woman is still spoken of as a "spinster." So perhaps might the term "cookster" be applied to women long after they have escaped that universal service.”

Power writes, “If old kitchens give you the creeps, then you’re normal. They reflect a world where women did not have careers, often did not go to college, and were not treated as equals.” Gilman thought that the way to solve this was to get rid of the private kitchen altogether and get our dinner from a centralized kitchen.

“Take the kitchens out of the houses, and you leave rooms which are open to any form of arrangement and extension; and the occupancy of them does not mean ‘housekeeping.’ In such living, personal character and taste would flower as never before… The individual will learn to feel himself an integral part of the social structure, in close, direct, permanent connection with the needs and uses of society."

There are problems with Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s vision; it was for white women only. She was a racist and eugenicist and thought black people could be trained to serve. (see Meg Conley for more on this) But she was not alone in believing that the way to liberate women from the kitchen was to get rid of it.

Christine Frederick wasn’t so radical as to suggest getting rid of the kitchen, and she didn’t have servants. She describes her life in her 1914 book “The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management:4”

“A moderate income, two babies, and constant demands on my time, was the situation that faced me several years ago. I liked housework, and was especially fond of cooking; but the deadening point about the whole situation was that I never seemed to finish my work, never seemed to "get anywhere," and that I almost never had any leisure time to myself.

My husband came home only to find me "all tired out," with no energy left to play over a song, or listen to a thoughtful article. I was constantly struggling to obtain a little "higher life" for my individuality and independence; and on the other hand I was forced to give up this in dividuality to my babies and drudgifying house-work.”

Frederick notes that this is a middle-class problem. The rich could afford to pay for staff and fancy kitchen equipment. “Money could always buy service.” For the poor, “their home-making is less complex and their tastes simple.” But Frederick’s middle-class women don’t sound like the women Power describes, without careers or education. Frederick describes them as the wives of ministers, bank clerks, college professors, and young men in business. “They are refined, educated women, many with a college degree or business training. They have one or more babies to care for, and limited finances to meet the situation.”

Frederick notes that only 8 percent of families in the United States keep domestic help and that every year, there are fewer servants as other opportunities open up, and “there will continue to be less, and the wages of those few will be higher.”

Frederick learned about Frederick Winslow Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management and tried to apply his principles to the kitchen. It wasn’t easy; Taylor broke tasks down into small repeatable elements, whereas in the kitchen, there are numerous different tasks, “and then the children want a drink, and I have to stop and get it!” But she studied everything, every movement. She then refines the kitchen design, minimizing the distance travelled. It was small, efficient, and dedicated to one function. A long quote:

“Many women are under the impression that a "roomy" kitchen is desirable. It may appear attractive, but a careful test of the way work is done in a "roomy" kitchen will discover waste spaces between the equipment, and hence waste motion between the work. Country kitchens are particularly apt to be large, and are often a combined sitting-room and kitchen. This plan seems cosy, but is inefficient because of the presence of lounges, flowers, and sewing all unrelated to the true work of the kitchen, which is the preparing of food. It is much wiser to have the kitchen small, and make a separate sitting-room so that the tired cook may rest in a room other than the one in which she has worked.”

Christine Frederick wanted an efficient separate kitchen so that she could cook quickly and get out of it to obtain a little "higher life.”

Lillian Gilbreth has been called “the mother of the modern kitchen.” She and her engineer husband invented filmed time/motion studies for industry, and having twelve children, she applied what she learned from industry to the family. Gilbreth put a radio in the kitchen; Alexandra Lange writes:

“The point of all this efficiency, after all, was to make the work of home-keeping just one part of a woman’s life. The life of the mind, and the outside world should not be alienated or separated from homemaking. Efficiencies should make time for other pursuits, and technology could allow you to think about other things, even while washing dishes.”

Open kitchens were common in Europe as well, with mom ironing, dad smoking and reading, and the kids doing homework; not a great situation for anyone. Radical socialists and hygienists didn’t like the idea of women being trapped in this environment all day.

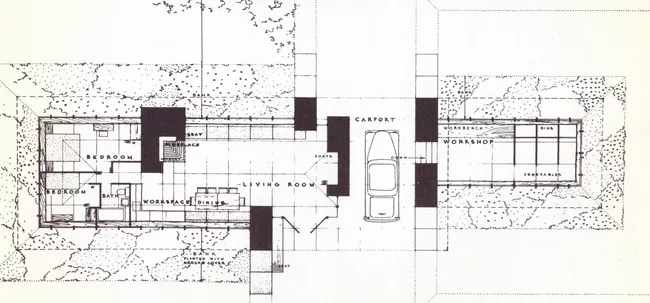

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, one of the first woman architects in Austria, worked on housing projects that were part of the Red Vienna housing boom. She had a German translation of Christine Frederick’s book and collaborated on a housing project in Frankfurt, where she developed what became known as the Frankfurt Kitchen.

According to Claus Bech-Danielsen of the Danish Building Institute, “the Frankfurt Kitchen was constructed on the basis of an analysis of workflow and storage needs. Spatial dimensions were also determined to optimize workflow.” It was small and efficient because it was supposed to be a machine for cooking.

(Matt Power illustrates his article with an AI-generated image that looks remarkably like a Frankfurt Kitchen, right down to the green paint, which Schütte-Lihotzky chose because a University of Vienna study found that green and blue finishes discouraged flies. His AI program is good!)

Paul Overy, in his book Light, Air and Openness, ties the Frankfurt kitchen to the Hygiene Movement from that period between the wars when people finally understood how germs cause disease but didn’t have antibiotics to deal with it. One architect wrote in 1933:

“The kitchen should be the cleanest place in the home, cleaner than the living room, cleaner than the bedroom, cleaner than the bathroom. The light should be absolute, nothing must be left in shadow, there can be no dark corners, no space left under the kitchen furniture, no space left under the kitchen cupboard.”

This is not a place for homework and backpacks. In this age of COVID and increasing antibiotic resistance, this is not something we should ignore, and Schütte-Lihotzky didn’t. Her parents died from tuberculosis, and she suffered from it too. Overy notes that she designed the Frankfurt Kitchen as if it were a nurses’ workstation in a hospital. Rather than the social centre of the house as it had been in the past, this was designed as a functional space where certain actions vital to the health and well-being of the household were performed as quickly and efficiently as possible.

In fact, it was specifically designed to make it almost impossible to eat in the kitchen. Another architect noted that he separated the kitchen from the dining room “to the great benefit of the family’s health,” designing it “as a passage of such narrow width that there is no space for family meals in the housewife’s laboratory.” He wrote:

“Our apartment kitchens are arranged in a way which completely separates kitchen work from the living area, therefore eliminating the unpleasant effects produced by smell, vapours and above all the psychological effects of seeing leftovers, plates, bowls, washing-up clothes and other items lying around.”

Schütte-Lihotzky designed the small, efficient kitchen with a social agenda; according to Paul Overy, the kitchen “was to be used quickly and efficiently to prepare meals and wash up, after which the housewife would be free to return to ... her own social, occupational or leisure pursuits."

All these kitchen designers shared one goal: to minimize the time spent in the kitchen so that women could do other more pleasant activities or have careers.

During The Second World War, many women entered the workforce and would have loved these efficient machines for cooking. But when it was over, they had to leave the factory and do a different job, and the kitchen became part of a machine for raising children. Part of the bargain was to open up the kitchen so that the whole house became the woman’s domain for this function. Kitchen technology had improved, new finishes like plastic laminates and vinyl floors reduced time spent cleaning, and the new world of frozen foods meant less time was spent cooking. Rose Eveleth writes:6

During World War II, American women found footing outside the home, and as the Cold War started to ramp up, the country became obsessed with innovation and automation. These future visions straddled that awkward set of goals: kitchens that were efficient and innovative enough to give women the free time they wanted, but wrapped in narratives that ensured that this time was spent not working, but rather doing wifely things like cleaning the rest of the house, sunbathing, and playing tennis.

Architects and designers jumped aboard this modern trend. Others looked back to earlier days; Frank Lloyd Wright reminisced about the farm kitchen that Christine Frederick hated, writing in The Natural House in 1954:

Back in farm days there was but one big living room, a stove in it, and Ma was there cooking—looking after the children and talking to Pa—dogs and gas and tobacco smoke too—all gemütlich if all was orderly, but it seldom was; and the children were there playing around. It created a certain atmosphere of domestic nature which had charm and which is not, I think, a good thing to lose altogether. Consequently, in this Usonian plan, the kitchen was called a ‘workspace’ and was identified largely as the living room."

So, the open kitchen took over. But did it make people happy? Did it work? A few years ago, this image was all over the internet after being published in an article titled “Here’s all the space we waste in our big American homes, in one chart.7 Half a dozen people sent it to me, "You see!" they write. "Everybody wants to live in the kitchen!" or "Open kitchens all the way. The kitchen should be the heart of the house, not tucked away out of sight and mind." Except I found the source, a 2012 study titled “Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century,8” which describes what’s happening here- it’s a mess.

Parents’ comments on these spaces reflect a tension between culturally situated notions of the tidy home and the demands of daily life. The photographs reflect sinks at various points of the typical weekday, but for most families, the tasks of washing, drying, and putting away dishes are never done. ... Empty sinks are rare, as are spotless and immaculately organized kitchens. All of this, of course, is a source of anxiety. Images of the tidy home are intricately linked to notions of middle-class success as well as family happiness, and unwashed dishes in and around the sink are not congruent with these images.

That German architect in the ‘30s worried about the “psychological effects of seeing leftovers, plates, bowls, washing-up clothes and other items lying around.” Now, we have to deal with many other kinds of distractions, and this study was done before the iPhone era.

“The limited minutes families spend eating are often entangled with other facets of life. Unrelated activities happen during one-third of dinners in our sample, usually centered on homework, television, or phone calls. As well, kitchen tabletops and even formal dining room tables in some homes are left fully laden with piles of bills, bulky toys, and the ephemera of daily living while diners are eating.”

Distractions mount to the point that one needs a separate kitchen for peace and quiet. Architectural critic Kate Wagner, who trained in acoustics, is one of the few who agrees with me about closed kitchens, writing in “Death to the open floor plan9”

“Not separating cooking, living, and dining is also an acoustical nightmare, especially in today’s style of interior design, which avoids carpet, curtains, and other soft goods that absorb sound. This is especially true of homes that do not have separate formal living and dining spaces but one single continuous space. Nothing is more maddening than trying to read or watch television in the tall-ceilinged living room with someone banging pots and pans or using the food processor 10 feet away in the open kitchen.”

In his article, Matt Power writes, “For most of us, decisions are shared, as are our chores and household “duties,” not dictated to our spouse or partner. Our kitchens should reflect that.” The numbers say otherwise; According to Gallup, women are still more likely to do the cooking and the laundry.

“Although women comprise nearly half of the U.S. workforce, they still fulfill a larger share of household responsibilities. Married or partnered heterosexual couples in the U.S. continue to divide household chores along largely traditional lines, with the woman in the relationship shouldering primary responsibility for doing the laundry, cleaning the house, and preparing meals.“

So our typical North American woman works all day, schleps home and then prepares dinner, and then has to look at all the pots and plates sitting on the kitchen island—no wonder more and more of them are ordering in. No wonder developers offer closed “messy kitchens” to hide the microwaves and the Kuerigs, where you toast your Eggos or unpack the Uber Eats. No wonder the online food delivery business is worth $242 billion and is growing at 12% per year10.

In 1915, Alice Constance Austin designed a socialist community with kitchen-less houses. “Food was to be cooked in a central kitchen and sent to communal patios by a series of underground rails. Dirty dishes are sent back to the central kitchen for cleaning. Laundry would be taken care of this way too.” Again, the idea was to “free women from the drudgery of unpaid domestic work.” Like Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s vision, Austin’s community was for white people; Meg Conley writes,11 “Applications to become a member of the commune were open exclusively to white socialists. The commune’s founder didn’t think it was “expedient to mix the races in these communities." Conley calls these visions chilling, dystopic and violent.

Today, the underground rails are replaced by legions of abused and underpaid workers on e-bikes who are making deliveries for Uber and other food apps, often food that is cooked in “ghost kitchens” with underpaid staff. Women are likely using these services because they are too exhausted to cook or don’t have the time. For many people, the open kitchen is a knapsack storage station, a reheating station and a waste management station for all the take-out containers. And it is sitting there, staring them in the face, likely a source of anxiety and stress.

Matt Power paints a bucolic image of the kitchen as a place which “allows parents to commune with kids, provides a space for serious conversations and education of family members, and a place to chat with guests as food is shared.” I could rewrite that image as a place with parents tripping over babies, homework covering the counters, and guests getting in the way when you are trying to get dinner together.

But I can’t support the dystopian Gilman/Austin/Uber Eats model of the central kitchen either, with its dependence on a class of underpaid workers. Instead, let’s bring back the tight, efficient, and separate galley kitchen, maybe the one that Matt Power hates “with slots and openings, like a short order kitchen.” Where you can cook, leave, and enjoy Christine Frederick’s “higher life,” and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s “social, occupational or leisure pursuits.” The open kitchen isn’t Matt Power’s “statement,” it’s a trap.

I highly recommend Christine Frederick’s book, its an easy read and a real trip. Free on the Internet Archive.

1 https://www.axios.com/2023/10/30/home-cooking-eating-pre-covid?t

4 https://ia600902.us.archive.org/24/items/newhousekeeping00fredrich/newhousekeeping00fredrich.pdf

5 https://jacobin.com/2023/06/margarete-schutte-lihotzky-frankfurt-kitchen-red-vienna-nazism-design

6 https://www.eater.com/2015/9/15/9326775/the-kitchen-of-the-future-has-failed-us

7 Here's all the space we waste in our big American homes, in one chart.

8 Life at Home in the Twenty-First Century

9 “Death to the open floor plan”

11

Our house is about 1650 square feet of conditioned space. It has an open kitchen/ dining/ living room of about 1000 square feet. We like the open space, but I guess not everyone does. On Christmas Eve, we'll have nine people for dinner. My wife will make most of the dinner, while everyone will crowd around the kitchen island, chatting with the cook and each other until we serve dinner at the dining table, which is in the center of the space. After dinner, we'll clear the table, piling the dishes on the kitchen counter while whoever wants coffee will make it. It's a bit messy, but after our guests leave, I'll clean up in just a few minutes. It's an efficient space.

We both cook, with each of us having certain dishes we like to make. Of the 21 meals in a week, we cook an average of at least 20.

From a use of resources point of view, our open plan has some advantages. We heat the entire space with a single mini split heat pump. Three separate rooms would require either separate heating appliances or ductwork. Three rooms would mean several partition walls requiring dozens of studs, a few hundred square feet of drywall, probably several doors. The living room end is on the south side of the house. It's nice to get sunlight in the entire space, especially this time of year when, because sun is low in the sky, we get sunlight penetrating all the way into the kitchen on the north wall. If we partitioned off the space, the kitchen would never get any sun.

Like a lot of people, I grew up in a house with a separate dining room. Like most dining rooms, it was almost never used.

An awful lot of people just don't cook. Having a separate kitchen isn't going to change that.

The paragraph describing Matt Power’s bucolic vision of the kitchen and with your counterpoint describing the identical space as something completely different says it all. Kitchens can fit either description, both or one anywhere in between. The kitchen in my childhood home was a basic U-shape opening to a space occupied by a large dining table. It was small enough that one person could work it efficiently but large enough that you could have three or four people in there working together on a meal for a large gathering (an almost daily occurrence at our house where at the peak we were 9 sharing a 1500sqft bungalow with one bathroom and where one or more of us routinely dragged home a stray or two to join us for a meal). It, together with the attached dining space shared the role of gathering place with the living room. It served as the scene for so many of my most important memories of family and friends. We cooked and ate there. We played board and cars games on the table. We argued there, we celebrated, laughed, cried and mourned there. We watched the moon landing there on a miniature portable TV borrowed from a neighbour. It was never just Mom’s space. Certainly she did the bulk of the heavy lifting there early on but we all were pulled in to help as we grew up and became capable. Even when my Mom was the “chief cook and bottle washer”, because it had some space and was joined to the dining area, she was seldom alone there. I still view having that space to share with family and friends during my formative years as one of the great blessings of my life. On the contrary, the cramped galley kitchen of one of the early apartments I shared with my later to be wife was useless except for its very narrowly defined purpose and was only mediocre at serving that purpose. It isolated the cook (having multiple cooks was not an option in there). It was cramped and claustrophobic. Its unpleasantness bullied you into eating out or ordering food. It played no positive role in bringing the people sharing the apartment space together. There is no perfect kitchen but I would argue that one that serves its purpose as a food prep and storage space and is set up in a way to bring people together trumps one that is designed for narrow purpose almost always. If you can’t hear your TV show because of all the banging pots in the kitchen maybe turn off the “idiot box” for a bit and go join the person in the kitchen banging those pots and make a meal and memory together.