Where do you start in your home to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions?

From the archives, where I tried to develop a new pyramid of conservation.

Over on Linkedin, UK Passivhaus developer Paul Richards complains,

“There must be a clear step by step guide for Home owners and occupiers, people are desperate to improve the efficiency and environment, but are lacking a guide as to what to do first, what are the small steps people can undertake without breaking an already stretched bank? Is there a common sense approach to retrofit?”

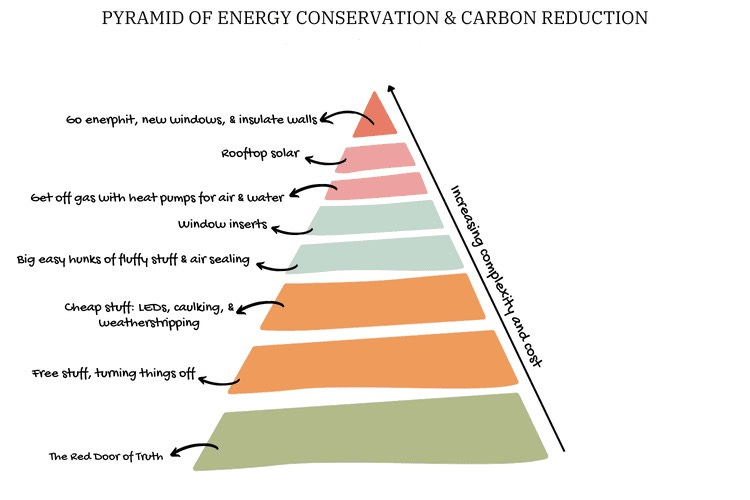

This is something I have thought about for years. I tried to develop a modern “pyramid of energy conservation” a few years ago for Treehugger. I have lightly updated it and reposted it here:

A Modern Pyramid of Energy Conservation

The Economist recently published an article around a problem it considers dire: draughty homes. It says, "Britain's homes are among the oldest and least efficient in Europe" and notes that "if people are to cut their energy use and benefit from lower bills in the long term, they will have to improve the energy efficiency of their homes." The piece offers solutions on how to fix the nation's 30 million draughty homes while helping Britain reach net-zero emissions, but these fixes raise sticky questions.

The Economist lists a number of steps, in order of difficulty, and calculates a payback period. It starts with:

Loft or attic insulation, the item that would pay for itself in three years

Wall insulation

Window Replacement

Heat pumps

Photovoltaic panels on the roof.

The problem is that this list is incomplete, it is not in the right order, payback periods are never very accurate, and it is not in line with current thinking about energy conservation and carbon emission reduction. Building science has advanced with concepts like Passivhaus, but while it and its renovation standard EnerPhit might be a thermal bridge too far for 30 million British homes, we can certainly learn from it. Let's see if we can figure out where to start and where we should go.

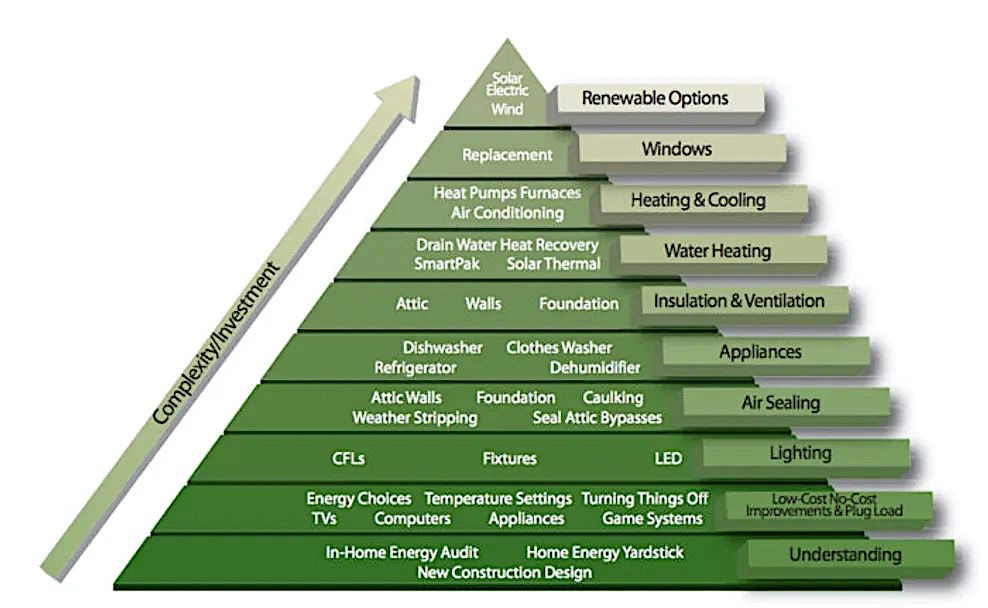

In 2006, electric utility Minnesota Power published the Pyramid of Energy Conservation, which recommended the order of what you should do when making a plan to upgrade your home for energy efficiency. You start at the bottom and move up, with each step increasing in complexity and cost.

It offended many people at the time, particularly the replacement window companies, closely followed by the furnace salespeople, who were appalled that their products were considered the last things that should be replaced. Much has changed in the world since 2006, especially with renewables, which cost a fraction of what they did then and would now put replacement windows right at the top of the pyramid.

Here is a pyramid that works today in a world where we worry about carbon as well as energy and have different priorities and technologies. Start at the bottom and work your way up. Or, if you want a list form with greater detail, start here and work your way down.

Get an audit that includes a full inspection and The Red Door of Truth, building science YouTuber Mark Wille's great name for the blower door test. If you are going to cut your energy consumption and carbon emissions, you have to know where they are leaking out.

Do the free stuff, including turning things off, lowering thermostats, and using a clothesline or horse.

Do the cheap stuff, like changing every lightbulb to LED, caulking, and weatherstripping. This is why the blower door is so important; for years, we have grossly underestimated the amount of energy lost through leakage. The Economist doesn't even mention it.

Do the big easy hunks, as energy pioneer Harold Orr called them. "If you take a look at a pie chart in terms of where the heat goes in a house, you’ll find that roughly 10% of your heat loss goes through the outside walls,” said Orr. About 30 to 40 % of your total heat loss is due to air leakage, another 10% from the ceiling, 10% from the windows and doors, and about 30% from the basement. “You have to tackle the big hunks,” said Orr, “and the big hunks are air leakage and uninsulated basement.” This would include The Economist's loft or attic insulation.

Get window inserts. They are a fraction of the cost of new windows but dramatically cut drafts and noise.

Get off the gas. This is a big step in cost but a giant leap in carbon emissions reduction. Change the furnace or boiler for a heat pump, and get a heat pump hot water heater. This will never pay back; you are still paying for energy, but it is key to going zero carbon. If you have done the big easy hunks, then the heat pump will likely cost less because it can be sized smaller for the reduced heating loads. This is what we mean when we write that we need to electrify, heatpumpify, and insulate our way out of the current crisis.

Install photovoltaics if your roof faces the right way, and your electricity supplier will buy the power from you.

Do a gut job and go enerphit—the Passivhaus standard for renovations. As noted in an earlier post, "Your home operates as a system. All of its elements—the walls, the roof, ventilation, heating and cooling systems, the external environment, and even the activities of the occupants—affect one another." Don't look at windows as a separate element, no matter what the salesman says. As engineer Robert Bowden noted on LinkedIn, "homeowners often replace older windows and door with new models, but the installers never remove the old trim work to repair the perimeter air leaks. These equate to holes as big as a pie plate." Or they insulate the outside walls and don't seal them properly for air tightness. If you are going to spend this much money—and it's a lot—then hire a Passivhaus consultant and do the whole thing right to reduce your heat loss and improve your air quality. There is no point in nickel and diming at this point.

I am not going to say The Economist gave bad advice, but you don't start with loft insulation when you have holes as big as pie plates all over your house. You start with data from the Red Door of Truth, with analysis by a professional who is not a window, foam, or furnace salesperson, and then you climb the pyramid of energy conservation and carbon reduction from there.

The most important measure is to work towards the space and fabric being heated and insulated, and the household equipment are meeting genuine housing needs. While over 50% of these resources are underutilised (ie due to under-occupation) the wasted space/fabric/equipment will be duplicated through new building emitting intolerable levels of upfront/embodied carbon. Balancing the size of dwellings and households is the classic win/win.

I definitely agree that the initial focus should be on recognizing what the efficiency issues are. And airtightness should come next. Most US codes now require a new house to be tight enough (3 air changes per hour at 50 Pascal of pressure, roughly equivalent to a 20 mph/30 kph wind, usually stated as 3ach50) to require mechanical ventilation. But most older house are not going to achieve that level of airtightness without a total gut rehab. So mechanical ventilation is not necessary in most existing houses. But going from 12ach50 (not at all uncommon) to 6ach50 will make a huge difference.

Use a blower door test with a thermal imaging camera to help figure where the leaks are.