We won’t have enough copper supply to meet demand within the decade. What do we do?

Some would say: open new mines as fast as possible! Or we could just use less stuff.

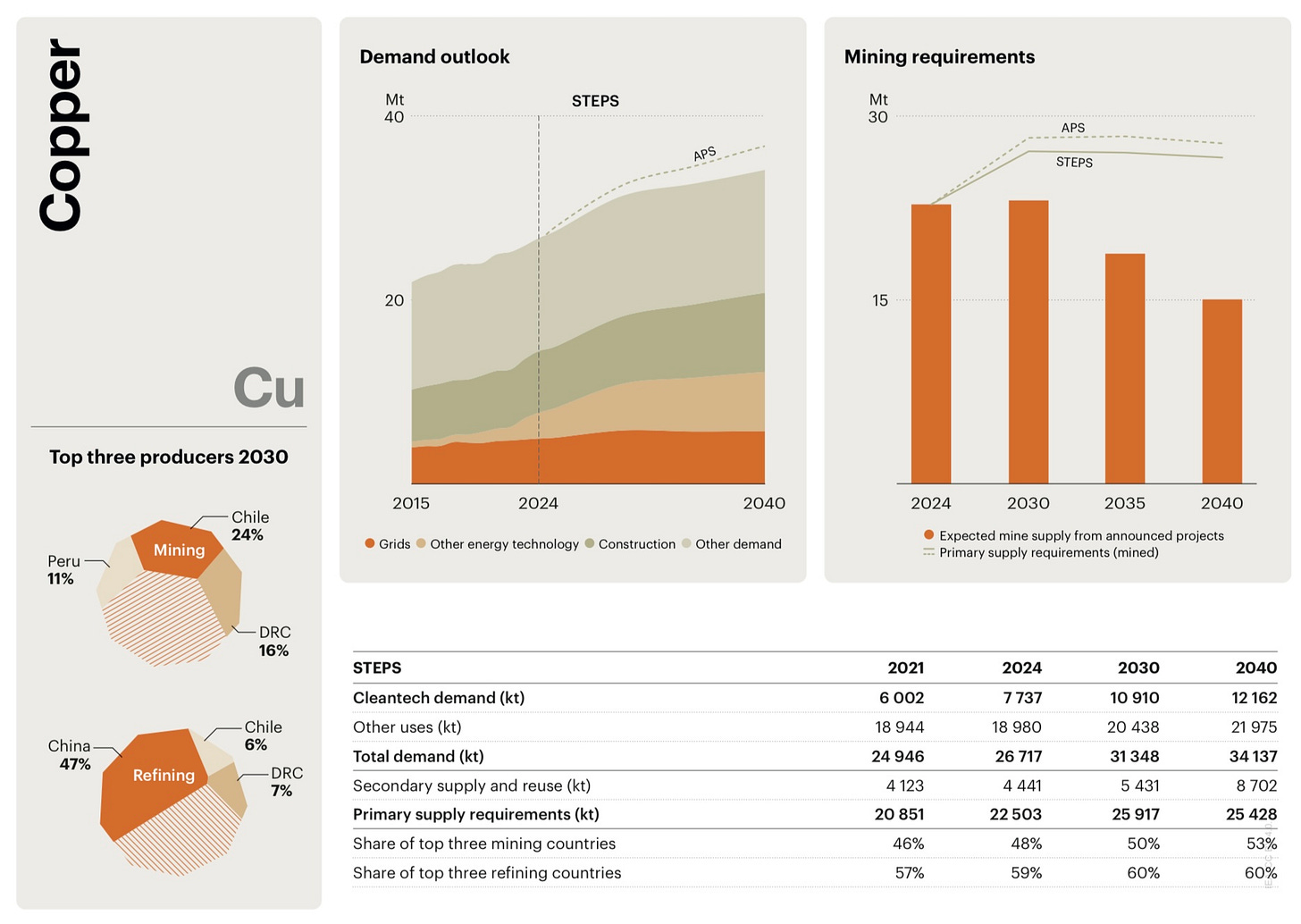

According to the International Energy Agency, demand for copper is going to outstrip supply within a decade. We are not going to run out of copper, but the concentration of copper in the ore has declined by 40% since 1991. In some cases, there is more copper in the tailings from previously mined ore than there is in the new ore- it gets harder and more expensive to process it.

Meanwhile, demand keeps increasing; according to the IEA,

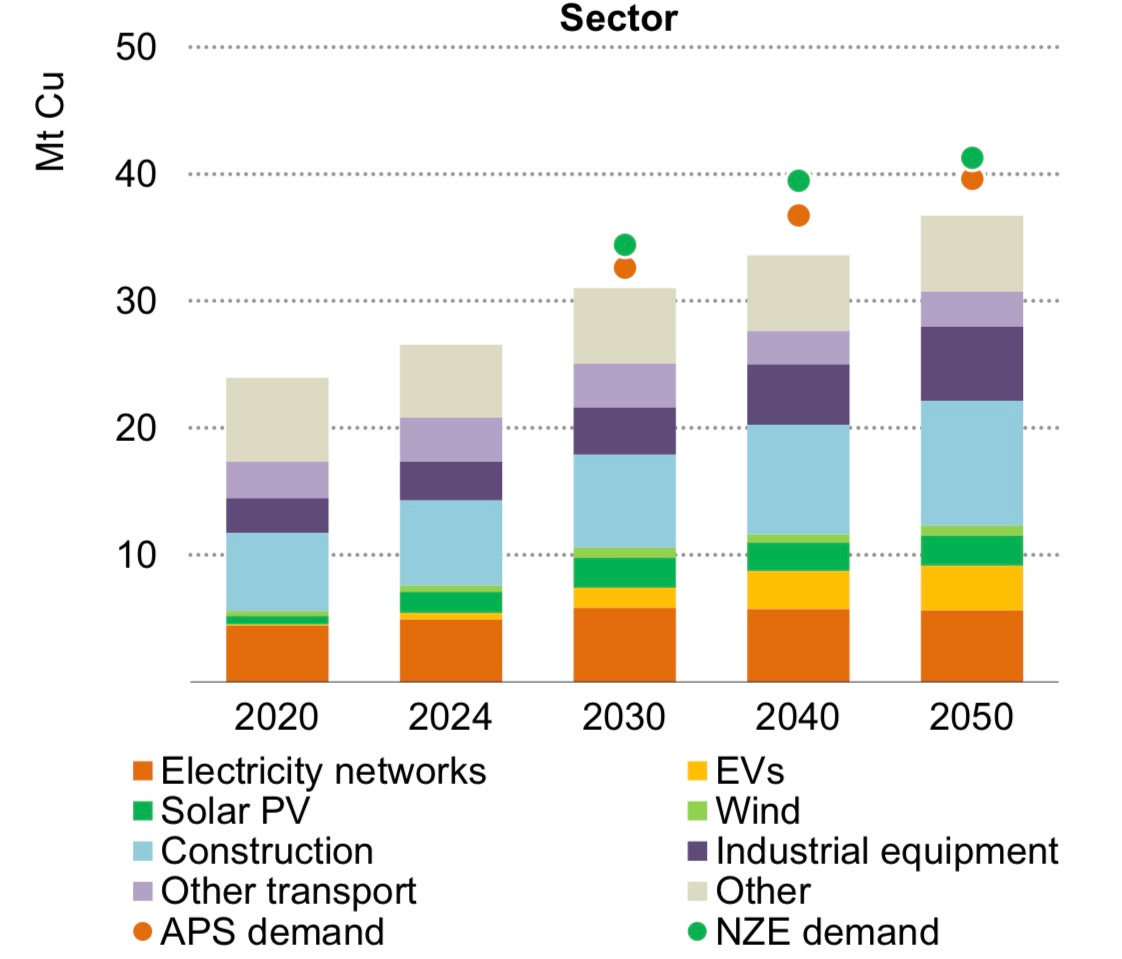

Global refined copper demand (excluding direct-use scrap) was almost 27 million tonnes (Mt) in 2024 and grows to reach almost 33 Mt in 2035 and 37 Mt in 2050. Construction and electricity networks remain the largest sources of copper demand, while EVs are the fastest-growing source of demand, increasing sevenfold from 2% of global copper demand in 2024 to 10% in 2050. Demand from industrial machinery and equipment almost doubles in the same time to reach over 15% of demand, driven by the increase in manufacturing and electrification across the world, while demand from solar, wind and construction all increase around 50% in this period.

Fatih Birol of the IEA says it is time to sound the alarm. He is quoted in the Guardian:

“[A supply crunch] is not inevitable. We can soften it if we move very fast, by putting new projects to market very fast, by recycling copper, and substituting copper with other metals such as aluminium, to alleviate the problem.”

But aluminum has its own issues. Birol always looks on the bright side of life, but if you read the IEA report, you see a supply crunch not very far down the road.

And once again, everyone talks about supply and never talks about demand. Nobody asks, “What is enough? What is sufficient?” Look at where the copper is going: the biggest chunk is construction, and the fastest growing chunk is electric vehicles. It gets bigger while “other transport” gets smaller. Do we need so many electric cars? Do they have to be so big? You can run 300 e-bikes with the batteries in one Rivian pickup truck, would we not be smarter to invest in making our roads safe for them?

Any driver knows that when you see a crash up ahead then you slow down. And here we have a significant shortfall in supply happening in the very near future. But nobody ever wants to slow down, particularly now when there is an abundance movement that wants to strip away regulations that might inhibit more and faster copper mining, and promises endless happy growth. Nobody wants to talk about the environmental cost of mining all this copper, but it requires huge amounts of energy and water. I wrote in my book, The Story of Upfront Carbon:

“According to the U.S. Geological Survey, in 2019, construction ate up 43 percent of copper. According to Copper.org, the average home has 195 pounds of copper wiring, fifty electric outlets, and fifteen to twenty switches. The wiring is designed to carry 1,800 watts of power to incandescent lightbulbs, vacuum cleaners, and TV sets.

Except the light bulbs now draw 10 watts. The TVs are thin LED screens. The vacuum cleaners are battery powered. Everything we plug in has a little wall-wart to convert the power from 120 volts AC to low-voltage DC. Most of that 195 pounds of copper are superfluous, as are all those little wall-warts because you can now wire your house with CAT-5 and just plug in a computer cable. As the building codes catch up, we will soon no longer have 120-volt wiring that can cause fires, electrocute children, or waste 195 pounds of copper when a tenth that will do. Our home wiring is being ephemeralized, and with it, a major source of demand for copper.

Copper isn’t the only material that we are running out of. Geologist Simon Michaux, working for the Geological Survey of Finland (GTK) did an assessment of the minerals and materials needed to replace fossil fuels and concluded that the quantities are enormous, and the timing is almost impossible.

Current expectations are that global industrial businesses will replace a complex industrial energy ecosystem that took more than a century to build. The current system was built with the support of the highest calorifically dense source of energy the world has ever known (oil), in cheap abundant quantities, with easily available credit, and seemingly unlimited mineral resources. The replacement needs to be done at a time when there is comparatively very expensive energy, a fragile finance system saturated in debt, not enough minerals, and an unprecedented world population, embedded in a deteriorating natural environment. Most challenging of all, this has to be done within a few decades.

Michaux calculates that car batteries on their own would eat up half the world’s lithium and nickel reserves. Furthermore, it gets harder and harder to get the metals out of the ore; there is less copper in a tonne of rock dug out of a copper mine today than there was left in the overburden of mines from a hundred years ago. This makes mining more expensive and more reliant on energy, primarily diesel fuel. Many mining processes use vast amounts of water; in his report “The Mining of Minerals and the Limits to Growth,” Michaux notes that “there is an inverse exponential relationship with water consumption and ore grade.”

We obviously need piles of copper to decarbonize. We need HVDC cables girdling the world, we need heat pumps, we need to electrify transportation. But we can make choices about where we put that copper. As degrowth proselytizer Jason Hickel notes in a Conversation article,

“Factories that produce SUVs could produce solar panels instead,” suggests Hickel. “Engineers who are presently developing private jets could work on innovating more efficient trains and wind turbines instead.”

Or we could practice sufficiency and simply use less stuff. We could go for micromobility instead of SUVs. We could go low voltage DC and cut the copper in construction in half. There is no copper in shoes; we could design walkable communities. We could put some efficiency standards on AI.

If you don’t like the words “degrowth” or even “sufficiency,” call it “demand-side mitigation.” The point is, we don’t have to live in a world where demand always exceeds supply; we can choose instead to reduce demand. And at some point, as the supply of resources gets tighter and more difficult to extract, that choice will be made for us whether we like it or not.

There is a Northern Ontario story where a mine mistakenly sold gravel from the "Process" pile rather than the "Tailings" pile. Resulting in the street literally being paved with gold. I think it was Timmins Ontario.

History suggests that we are incapable of self regulating our consumption at scale. We change behaviour only when immediate circumstances leave us no viable alternative. Without serious pain our idiot brains simply conclude we are doing fine and keep us chugging along as if we are immortal and the world is a limitless provider of whatever we want. The end of this civilization is nigh. At some level we all know it but not in a way that creates enough psychic or physical pain for us to change our behaviour in a material way (buying an electric car and diligently putting out our recycling won’t cut it I am afraid). Conflict between our immediate self interest and the needs of the future is always resolved in favour of the now. Nothing in our history suggests we are capable of better as a group. We are products and victims of our evolution. Voluntary degrowth would entail a level of foresight and active reasoning that is beyond the capabilities of the collective. Even if it were not, we have created a civilization supported precariously on the untenable notion that because having some stuff is good having more stuff must be better. Time for a (another) reality check for humanity. Assuming there is anyone left to write our history they will no doubt be astounded by our wilful blindness to the inevitability of the collapse of what is clearly a house of cards in the path of a hurricane. Based on past cycles they will probably also promptly head off down the same path that got us here. God is clearly a sadist.