Upfront Carbon helps kill replacement of Marks & Spencer's Oxford Street store

We will be seeing more of this worldwide as embodied carbon is taken into account. There are lessons here that apply everywhere, including Toronto.

The fate of Marks & Spencer’s Oxford Street store has been in the news for some time; I wrote about it on Treehugger almost two years ago, noting that while a few voices worried about the upfront carbon that would be released building its replacement, “everyone else there is either carbon illiterate or is studiously ignoring the truth about the importance and scale of upfront carbon emissions because everyone is having such a good time knocking buildings down and building bigger ones.”

But now, to many people’s surprise, the British Secretary of State, Michael Gove, has rejected the application, with a major reason being that demolishing and replacing it would generate almost 40,000 tonnes of upfront carbon emissions. This is, so far as I know, only the second time that upfront carbon has been successfully used as a reason to oppose demolition. It won’t be the last.

Dezeen writes that “A 127-page report was released today by the Department of Housing & Communities to announce Gove's decision.” But they probably didn’t read it; in fact, it is a 14-page rejection attached to the earlier 110-page report by inspector David Nicholson, who concluded: “that the application should be approved, and planning permission granted.”

Nicholson acknowledged the importance of upfront carbon, writing, “Of the material considerations of which to take account, the extent of embodied energy that would be required weighs most heavily against the scheme.” but accepted the architect’s statements that the new building would perform better over its lifetime. Notably, he concludes that “As policy is still developing in this area, the SoS [Secretary of State] is entitled to use their judgement to give this consideration greater weight than I have attributed from current policy alone.” Which is, apparently, exactly what he did.

The best definition of the carbon problem in Nicholson’s report is architect Julia Barfield’s submission, which also explains how the world view of carbon emissions is changing quickly, with governments accepting that we are in a planetary emergency.

“She highlighted that the IPCC told us in 2018 that we have 12 years to avoid a catastrophe, and we see growing evidence all around the world that it is happening – with floods, droughts, fires and melting ice caps. Instead of acting as if there is an emergency, by proposing to throw a huge carbon bomb unnecessarily into the atmosphere, the scheme misunderstands the urgency of our situation. What the science tells us is that what we do in the next 8 years is critical. The brief here was clearly to maximise the site’s potential and the architects have fulfilled their brief well – creating a building minimising operational carbon that 5-8 years ago would have been considered fine. However, now that we understand the upfront impact of embodied carbon it really isn’t. Particularly building two extra basements! They are the worst in terms of embodied carbon.”

This is why I pound my head on the table back home in Toronto every time it is proposed to knock down a 20-storey apartment to build a 60-storey apartment or to build a massive glass and concrete spa on the waterfront: what was fine 5-8 years ago no longer is. Underground parking is a carbon bomb, as is a glass, aluminum and concrete superstructure. The whole project is an Oppenheimer-scale carbon bomb. They don’t get that in Toronto yet, but in London, they are beginning to.

It is also interesting to note that Inspector David Nicholson is not an embodied carbon neophyte; he was also the author of the report that killed the Tulip, Norman Foster’s silly restaurant-on-a-stick, writing at the time:

“Although considerable efforts have been made to adopt all available sustainability techniques to make the construction and operation of the scheme as sustainable as possible, fulfilling the brief with a tall, reinforced concrete lift shaft, would result in a scheme with very high embodied energy and an unsustainable whole life-cycle.”

So upfront or embodied carbon is now on the table in the fight to save and renovate existing buildings or to fight new silly and unnecessary ones, like the Tulip or the Therme spa in Toronto.

As always, when historic buildings are proposed for demolition, or silly new projects proposed, the architects promise that what will be built will be green and sustainable. Fred Pilbrow noted at the time that M&S would be BREEAM “outstanding” and WELL Platinum, as do the proponents of the spa in Toronto, who promise “a LEED Platinum standard and the highest levels of sustainability.”

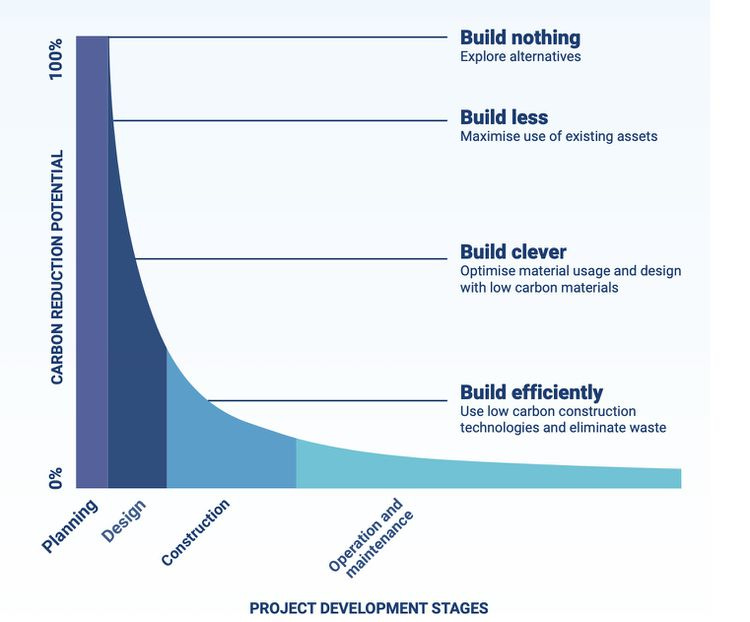

But that’s not good enough anymore; now we have to ask why are we doing this in the first place. As the World Green Building Council notes, if you care about carbon reduction, you first build nothing, and then you build less, maximizing existing assets.

As Julia Barfield noted, the world is changing. In the aftermath of the M&S decision, Ben Flatman writes in Building Design that heritage advocates used to be seen as fuddy-duddies or reactionaries or NIMBYs, and that many architects “still harbour a view that old buildings simply stand in the way of modernity and progress.”

“But a younger generation, energised by their outrage at the previous generations’ inertia on climate change, have embraced old buildings. Not necessarily out of an interest in heritage (although this doubtless plays a part) but because demolition and new build is seen as wasteful, and unsustainable.

Those who advocate for architectural conservation are now the natural allies of young architects, who see new build as almost unjustifiable – perhaps even immoral. The world in which old buildings were swept aside without a second thought, and new builds were designed with 30-year lifecycles seems increasingly at odds with this new mood.”

Indeed, there is a new mood; it is a new era, when what was considered fine 5 years ago no longer is. Conservative minister Michael Gove wrote that he refused permission because the project would “fail to support the transition to a low carbon future, and would overall fail to encourage the reuse of existing resources, including the conversion of existing buildings.”

This is a standard that should be applied everywhere, including in Toronto.

IMO a compromise is in order--don't demolish old buildings if we can reuse them, but don't prohibit exterior insulation retrofits either. All too often exterior insulation is prohibited to preserve historical aesthetics, even though 1) stucco on masonry retrofiting is perfectly historical process and 2) exterior insulation protects the structure from the more extreme future climate while interior insulation makes the structure more vulnerable to it. Save the structure, yes, keep it beautiful, yes, but don't insist on keeping the original aesthetics as is.

Whoever designed the proposed new store is obviously a plant from the preservation community. Nobody could seriously suggest replacing the existing, lovely building with that 70s inspired monstrosity.