Tomatoes are an object lesson in why we should eat local AND seasonal

Hothouse tomatoes have a big environmental footprint.

The author of a recent post on Bluesky was impressed that hothouse tomatoes from Canada (mostly from Leamington, Ontario) are available even in the United States.

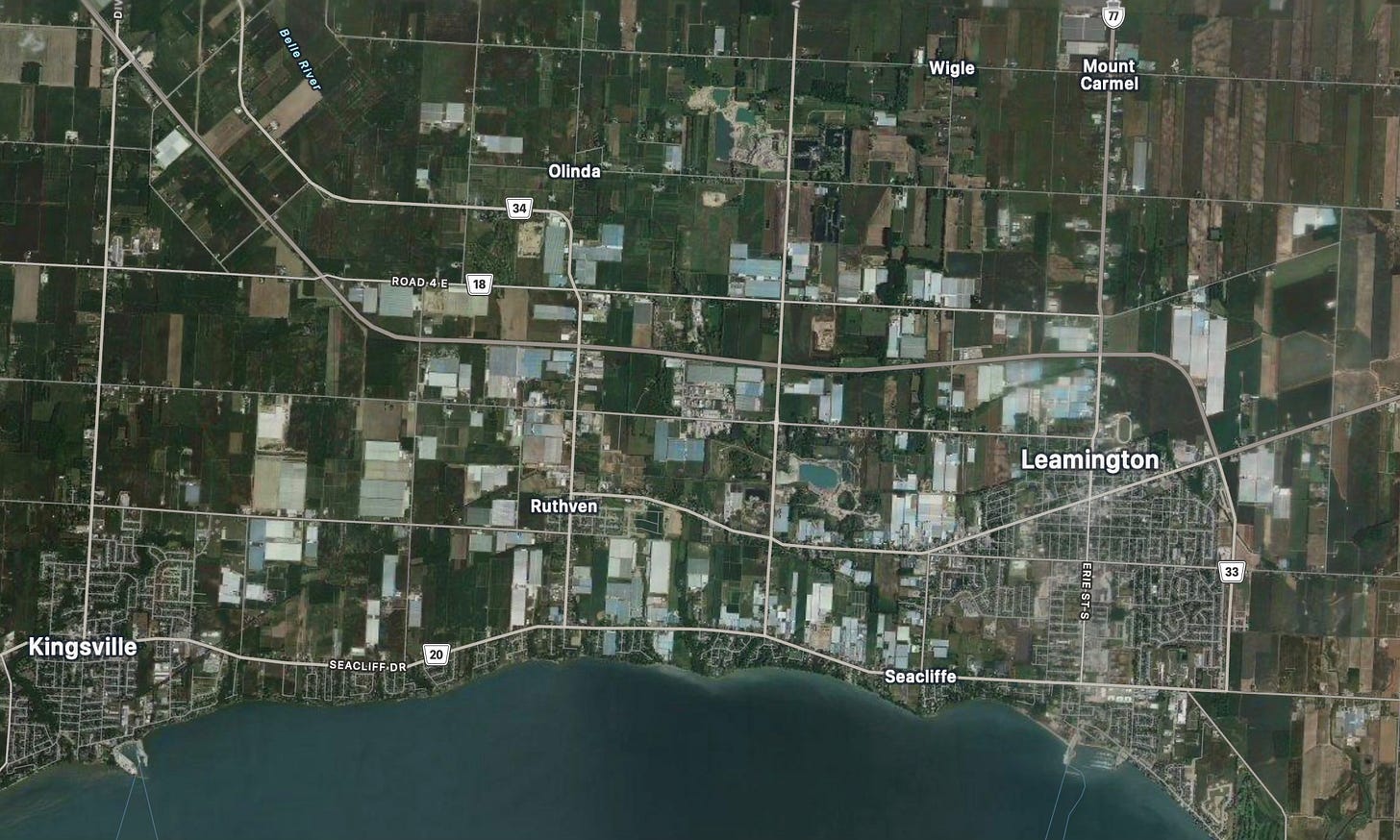

It’s a big industry; Leamington and Essex County produced 644,207 metric tonnes of tomatoes in 2024. Apple Maps shows how the area is covered in greenhouses.

Many people think this is a wonderful thing, being able to eat a local tomato in January. It could be part of the Patriotic Canadian Diet I have been pushing. The problem is, you are really eating fossil fuels. Vaclav Smil, in his book How the World Really Works, (my review here) devoted a couple of pages to tomatoes and their fossil fuel footprint, noting that heating is the most important direct use of energy in greenhouse cultivation of tomatoes, followed by fertilizer. He describes a Spanish tomato’s voyage to a Scandinavian table:

“When bought in a Scandinavian supermarket, tomatoes from Almería’s heated plastic greenhouses have a stunningly high embedded production and transportation energy cost. Its total is equivalent to about 650 mL/kg, or more than five tablespoons (each containing 14.8 millilitres) of diesel fuel per medium-sized (125 gram) tomato! You can stage—easily and without any waste—a tabletop demonstration of this fossil fuel subsidy, by slicing a tomato of that size, spreading it out on a plate, and pouring over it 5–6 tablespoons of dark oil (sesame oil replicates the color well). When sufficiently impressed by the fossil fuel burden of this simple food, you can transfer the plate’s contents to a bowl, add two or three additional tomatoes, some soy sauce, salt, pepper, and sesame seeds, and enjoy a tasty tomato salad. How many vegans enjoying the salad are aware of its substantial fossil fuel pedigree?”

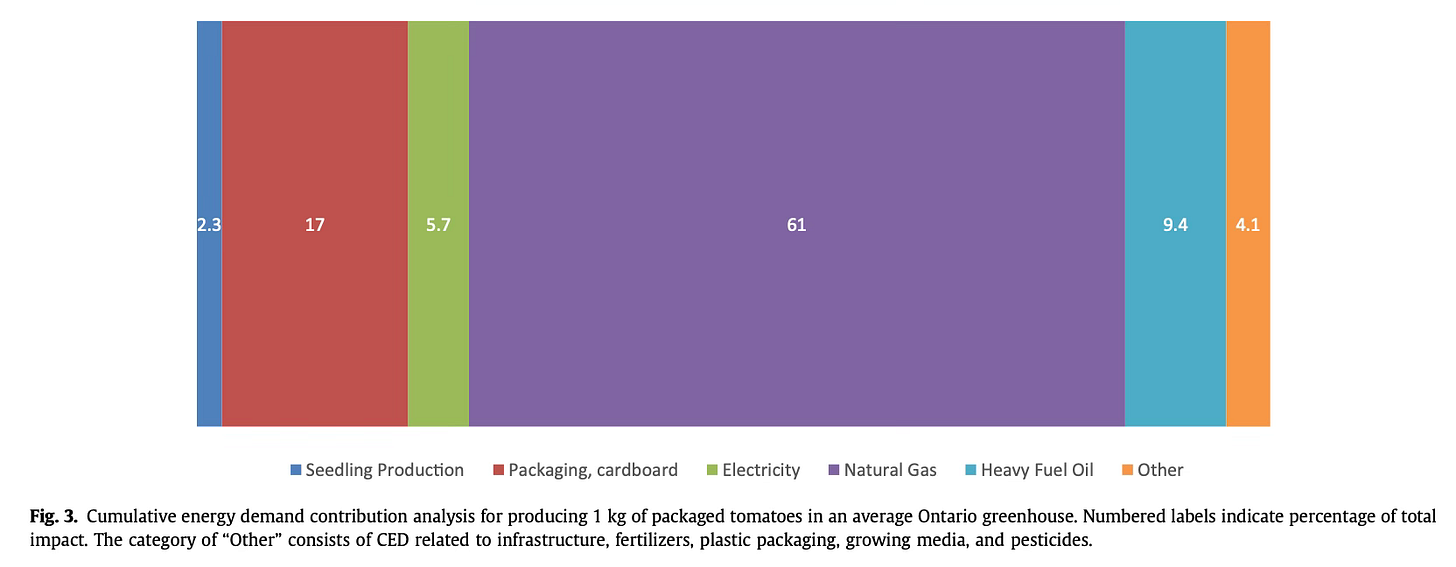

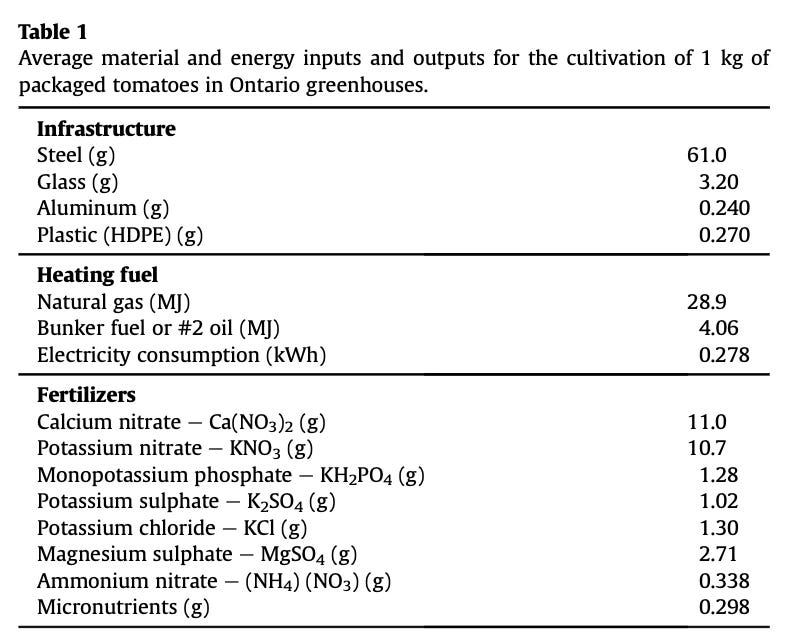

A 2017 study, Life cycle perspectives on the sustainability of Ontario greenhouse tomato production, is not very appetizing. It found that the production of a kilogram of tomatoes consumed 28.9 MJ of natural gas and 4.06 MJ of bunker fuel or #2 oil (for the greenhouses not connected to gas). Burning the natural gas for a kilogram of tomatoes releases 1.3 kilograms of CO2.

Smil also notes that “greenhouse tomatoes are among the world’s most heavily fertilized crops: per unit area they receive up to 10 times as much nitrogen (and also phosphorus) as is used to produce grain corn, America’s leading field crop.” I cannot figure out how much CO2 is emitted in making the fertilizers, but as I wrote in my book, Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle,

“Fertilizer is made from ammonia, which is made from hydrogen, which is made from natural gas. That makes it a fossil fuel product; for every molecule of ammonia produced, a molecule of CO2 is a co-product, so when we eat food made with nitrogen fertilizers, we are essentially eating fossil fuels."

This is why, every August, my wife Kelly buys boxes of field tomatoes and spends a few days processing them, so we have tomatoes in in January that don’t come from greenhouses. I noted in an earlier post that “If you are eating hothouse tomatoes, you are eating natural gas. If you are eating imported tomatoes, you are dining on diesel.”

This is why it’s not enough to eat local; you have to also eat seasonal. I wrote about this in my book, Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle; Here is an excerpt:

A decade ago, everyone was talking about the 100-mile diet, an experiment carried out by Vancouver writers Alisa Smith and J.B. MacKinnon where they ate food grown within a hundred miles of where they live, promoting the concept of local food. It was a fascinating and successful venture, turning into a book and a TV series.

I was writing about environmental issues for Treehugger and Planet Green, a website and a Discovery TV network that showed the 100-Mile Diet series. Meanwhile, I would go to dinner at my mom’s house, and in the middle of winter, she would be serving fresh asparagus flown in from Peru. I would explain how bad this was, and she would respond that she had grown up in the Depression when she would have no vegetables but potatoes. Then, in the fifties, she had canned vegetables, and in the sixties, frozen. She thought that it was just about the most wonderful thing in the entire world that she could go to the neighbourhood supermarket in the middle of winter and get fresh asparagus, and she was proud to serve it.

Meanwhile, I was having my own doubts about the 100-mile diet, and about the importance of local food. I was concerned about carbon emissions, and low mileage didn’t necessarily mean low carbon; research showed that a local hothouse tomato served out of season had a far higher carbon footprint than a tomato trucked up from Mexico.

My wife Kelly was writing about food for Planet Green at the time, and we became convinced that a seasonal diet was as important as a local one and ran our own experiment: the nineteenth-century Ontario diet. Ontario has a short growing season and a long winter (much longer in the nineteenth century), so the diet was wildly variable. In the spring, the asparagus was succulent and wonderful, so much better than my mom’s. In July, the strawberries were to die for, bearing no resemblance to the wooden ones from California. In August, tomatoes. So many tomatoes, in so many salads and pastas. Kelly would buy them and everything else by the bushel, and spend weeks canning them to get us through the winter.

By December or January, it was a different story. Potatoes. Turnip. Parsnips. More turnip. Root vegetable after root vegetable, and meat, lots of pork and chicken because, back in the nineteenth century, animals could huddle together to stay warm until they were butchered and served. There are many interesting ways to cook a potato or a turnip, but by March, we were counting down the days until asparagus.

But I now love turnip and the excitement and pleasure that comes with the first asparagus, corn, or blueberry of the season. All these years later, we never buy Mexican or hothouse tomatoes; we still have jars and jars of them from last summer’s canning.

We are not so doctrinaire anymore and will occasionally buy a head of lettuce in January and a few limes for a margarita. But neither of us ever wants to look at a California strawberry or a hothouse tomato again.

Lloyd - a partial rebuttal. Living in Calgary, we buy tomatoes from solar-powered nurseries/greenhouses in Redcliff, AB, which is next door to Medicine Hat, the sunniest city in Canada. The alternative would be to buy Mexican field tomatoes, subject to a lot of diesel before being delivered and eaten here. Apartment living doesn't allow for storing large quantities of home-preserved tomatoes, etc., so we believe we are doing our best. "Don't eat winter tomatoes!", you said under your breath? I would rather support local co-operatives and eat (relatively) fresh organic, locally grown produce than import 'foreign' tomatoes, or even try to do all the preserving!

That fossil fuel comparison with the sesame oil visual is kinda genius. I never thought about hothouse produce as basically eating natural gas but it tracks completely. The seasonal eating thing makes sense too - like yeah eating turnip for months sounds rough but theres something real about that delayed gratification when asparagus season actualy comes around. Most ppl dunno how carbon intensive those winter tomatoes are.