The wood revolution in building is just getting started

Architects are learning how to use less of it, and how to make it even more beautiful.

I have been radio silent here and on social media for the past few weeks, feeling guilty about visiting Ireland and the UK to gather information for my upcoming book on upfront carbon. One of the issues I have been trying to wrap my head around is the question of “how good is wood?” How much carbon does it really store or save compared to other materials that we use in construction? I have asked dozens of experts and have received dozens of answers. So much depends on how you define it. As I note in my upcoming book from New Society Publishers, The Story of Upfront Carbon,

Carbon savings with wood construction are counted in two ways: Avoided emissions, when compared to what might have been emitted If building out of concrete or steel. I always thought this was silly, like being on a diet and counting the calories of the chocolate cake I didn’t eat instead of counting only the calories I did. Others disagree, with the American firm Kirksey Architects writing that “Studies accounting for long-term carbon dynamics of wood products shows that the substitution effect of avoiding fossil fuel emissions is even more significant than carbon stored in wood.”

The other carbon saving is from carbon storage in the wood; according to the Mass Timber Institute, “It is estimated that one cubic metre of mass timber sequesters one metric ton of carbon dioxide.” Some have said this is so wonderful that we should use more wood and store more carbon! But as British engineer Will Hawkins notes,“accounting for sequestered carbon is often a source of debate, confusion and inconsistency. When sequestration is reported as a negative emission, it can create the counterintuitive impression that using timber excessively can have environmental benefits.”

A comparison of two buildings that I visited demonstrates my quandary. While visiting Hereford, Engineer Nick Grant took me to the Centre for Advanced Timber Technology (CATT) at the New Model Institute for Technology (NMITE). Tabitha Binding, Head of Education & Engagement at Timber Development UK and Lead for External Engagements & Partnerships at NMITE, conducted a tour.

A design competition for the building was won by Hereford-based, oak-framed building specialists, Oakwrights, to be built by Speller Metcalfe. Alas, that design was too expensive, so architects Bond Bryan developed a different design with the big workshop spaces to the right in the picture above built with steel portal frame construction. Tab Binding expressed some disappointment that it wasn’t built with wood, but one could make the case that for big spans of industrial space like this, light steel makes the most sense.

The office and meeting spaces are built out of Glue-laminated beams and columns and Cross-Laminated Timber slabs. Seeing the minimalist steel structure next to the wood raised all those questions- in the wood building, the beams are huge, the detailing is clunky, and the roof structure could have been done with a fraction of the fibre had they built with joists instead of slabs.

A few kilometres away in Hereford, Passivehouse builder Mike Whitfield uses truly innovative wood construction with lightweight I-joists, running them the “wrong” way as purlins instead of rafters to save a ridge beam and use less material. There is probably less fibre in this entire house than there is in one roof panel in the CATT.

The CLT supplier Stora Enso case study of the building revels in the amount of wood in the CATT, (well, they would, wouldn’t they?), noting that the 289 cubic meters “will take only two minutes on a summer day in the Austrian forest to grow back.” They note that “220 tonnes of carbon dioxide were removed from the atmosphere when the trees were growing and will be safely stored inside the building’s lifetime” without accounting for the rotting roots, the kiln drying (which may be with wood waste but is still creating “now” emissions”) or the transport from Austria, all of which might well add up to another 220 tonnes of carbon dioxide, given that some research puts the carbon savings at no more than 50%.

NMITE says they wanted to “showcase as many different ways of using timber as possible within the building,” but the view of the ceiling is often blocked by silly white panels. I thought the building was a demonstration of how not to build with mass timber, with needless complexity and too much fibre, which I suppose is useful in a building designed for timber education. I thought of the words of another Hereford resident I met that day, Andy Simmonds of the Association for Environment Conscious Building (AECB), who wrote with Lenny Antonelli in PassiveHouse Plus:

"Use natural resources extracted from our shared biosphere respectfully and efficiently to substitute for higher embodied carbon materials. Use as few materials as possible to achieve the design. Using a “renewable” material inefficiently, whether to ‘develop the market’ or ‘store carbon’ is wrongheaded – efficient use of the same quantity of material, substituting for higher carbon options across many projects, makes far more sense."

Returning to London, Andrew Waugh of Waugh Thistleton Architects took me to his recent Black and White Building, built with a frame of Laminated Veneer Lumber (LVL) and CLT slabs for walls and floors. The developer TOG has noted, "[The building is] a new approach to workplace design. In The Black and White Building, they have explored an ‘architecture of sufficiency’—where every element serves a purpose, nothing is superfluous, and all materials and processes are as efficient and sustainable as possible." LVL is strong; Andrew Waugh explained earlier that LVL “allows us to design significantly smaller cross-sections for beams and columns than softwood whilst maintaining a high-quality surface finish from a raw material sourced from sustainable, managed forests." He told me that it is also far more efficient in its use of fibre, peeling 90% of the log as veneer.

I was shocked at how slender the columns and beams were, looking not much bigger than steel would be after it is enclosed in drywall. They are all bolted together, designed for disassembly. Waugh said proudly that they now use 40% less wood fibre per square meter than when they started working with CLT.

The basement level is made of poured concrete, but Waugh has done perhaps the nicest board-formed concrete since the National Theatre. There is also a big bike parking garage, but Waugh complains: “To justify the amount of concrete that went into that bike parking, one would have to ride each bike for 110 years.” He says we have just to stop building basements, a point made by another architect I met in London, Kelly Alvarez Doran, who found that even in low-rise wood buildings, the carbon in the basement can be half that of the entire building.

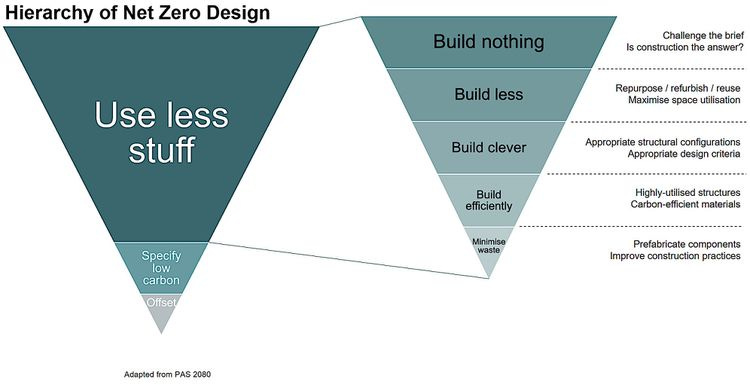

So what did I learn from all of this? Frankly, it is mostly a confirmation of what I had learned before from so many of the people I met. Engineer Will Arnold’s three words: Use Less Stuff, a rephrasing of sufficiency and Andy Simmonds’ “Use as few materials as possible to achieve the design.” Kelly Alvarez Doran’s carbon iceberg. Nick Grant’s simplicity. I also talked with Mark Sidall, Alan Clarke and Jeff Colley of Passivehous Plus, who assembled a dinner party of all the best architects and passive house people in Dublin, including Tomas O'Leary and Ciarán Cuffe.

In the end, I still do not know how much carbon is saved by building with wood. But I am convinced that we have to build less, and when we do build, we have to do it with an eye to sufficiency and simplicity. Carbon storage in wood is important, but we still should use as little of it as possible. And maybe avoided emissions from using wood instead of concrete is worth counting, especially if it means I can now have chocolate cake for dessert.

And while it is still difficult to justify a trip across the ocean, the experience of riding in a soapbox derby car built by Nick Grant, Juraj Mikurcik, Mike Whitfield and friends will never be duplicated on Zoom.

This is fabulous Lloyd - and sounds like one hell of a dinner party!

Great article Lloyd. Thanks for putting this together. It hits on some things I have been thinking about and other things that never occurred to me.