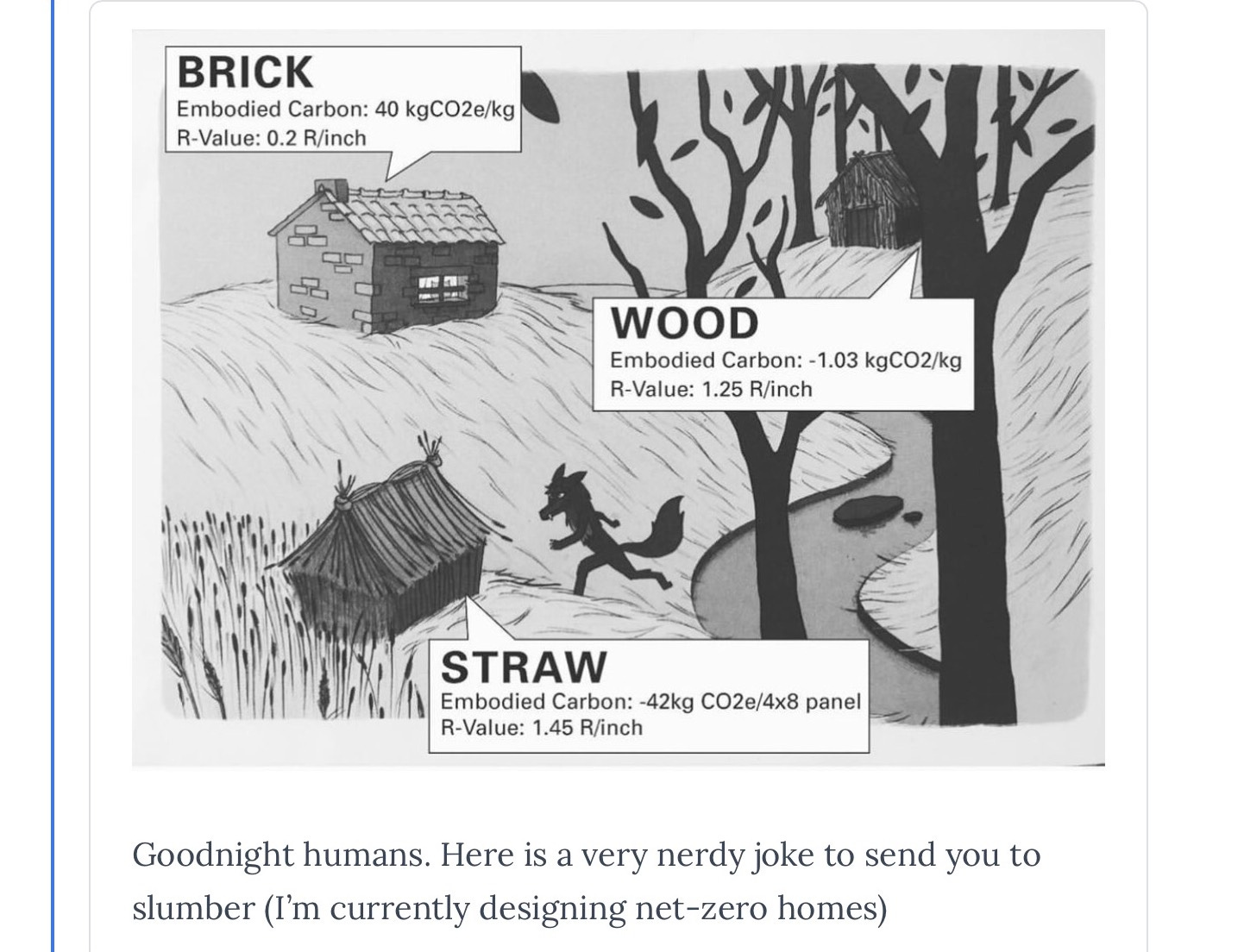

The three little pigs got it wrong

When it comes to upfront carbon emissions, straw is a lot better than brick.

In my upcoming book from New Society Publishers, The Story of Upfront Carbon, I conclude my chapter on construction with a discussion of low-carbon materials.

“Perhaps the most pernicious story ever written was The Three Little Pigs, with its very English conclusion that houses should be made of brick. The future we want is built of sticks and straw.”

Three little pig jokes appear to be fairly common when discussing straw construction. The Financial Times writes about straw:

Building with straw may evoke the image of a furry aggressor and three unlucky pigs, but designer Jonathan Davies, who works with UK straw bale construction company Huff and Puff, says it is a surprisingly robust material. “You don’t have to have a little straw hut,” he says. “You can, in fact, build something that delivers an exemplary level of energy efficiency.”

Huff and Puff Construction (Great name!) build out of straw bale, which can be load-bearing or infilling a timber frame.

I have been excited about prefabricated panelized straw, as used by Juraj Mikurcik for his own house in Hereford, which I visited with Nick Grant in May. Juraj’s photo of his dog sitting in the chair beside the window has been my go-to shot to demonstrate the comfort delivered by the Passivhaus standard. But the house is also a great demonstration of the EcoCocon prefab straw building system.

A bit of a panel has been turned into a coffee table, so you can see how it is made. The FT notes that most straw is wasted; some is ploughed into the soil, and some is burned. But at a time when we are worried about the upfront carbon emissions of our building materials, it might be the perfect solution for insulation; it grows fast and stores a lot of carbon. As architect Cameron Sinclair tweeted in yet another Three Little Pigs joke:

Juraj tells the FT: “It stores heat in the winter and keeps you cool in summer,” he says, adding that straw’s abundance could allow houses such as his to be mass-produced. “We could build tens of thousands of houses every year.”

The house is a warm and comfortable mix of polished concrete floor and plaster walls. Juraj explains:

“Clay plaster works brilliantly when applied directly to straw, as it allows moisture to permeate back & forth, effectively acting as a moisture buffer. It’s a healthier option compared to cement or gypsum plaster and will add significant thermal mass to the building – we have 7 tonnes of it to put on walls!”

The plasterwork is lovely and curves into the window opening so that there are no sharp corners that might chip off. The wood stove is there as insurance for the coldest days and is rarely used; most heat comes from two towel warmers in the bathroom that are connected to the water heater. Juraj notes in a blog post that “In hindsight, we’d probably not install the wood stove if we started with the build again – we have a beautiful air quality in the house, so why make it worse with burning wood, even if it’s just a meter cubed of wood per heating season?”

Overheating can be a problem in Passivhaus designs, but not here; Juraj told me back when I covered the house in Treehugger how he survived a heat wave:

“I feel it's been a combination of careful window design, robust shading strategy, inclusion of useful thermal mass (concrete slab and clay plasters applied to straw and heavy Fermacell boards) and religious night time purge that all helped to keep the house nice & comfy. Seriously, at times it felt like coming in to an air-conditioned space when the temperature and humidity was considerably higher outside.”

I also like his choice of books. Read more at the Old Holloway House blog.

Leah Quinn of the FT also talks to Craig White of Agile Homes, who explains some of the benefits of prefab panels. “Chopped straw allows for a number of improvements over bales,” White says. “We can vary the thickness of walls more precisely to balance density, thermal performance and carbon capture.”

I have not met Craig in person but talked to him at length about his work, which blew me away, not just because of the panel but the entire business model. In my Treehugger post, I noted that in my prefabricated housing career, “I tried to do much of what Agile is doing, and I did almost everything wrong—a major reason I am now a writer. I look at what Agile is doing, and I am very impressed because, based on what I learned, they are doing almost everything right.”

Craig had previously developed the ModCell prefab straw panel and uses it in Agile Homes to build affordable housing.

Where Ecococon panels are built in a factory in Slovakia, Craig keeps it local, telling me: that their "model of prefabrication is not to do it from centralized factories but to unlock the potential of assembly using an international standard to manufacture in temporary facilities which might be somebody's warehouse to colloquially have 'flying factories' or technically, 'distributed manufacturing.'"

Recently two major prefab housing companies in the UK have failed for the reason that so many do: big overheads and high fixed costs. I have seen this movie before, most spectacularly with Katerra in the US. Craig keeps it simple with plywood and straw buildings, low overheads and an interesting business model. I concluded in 2021:

“I have watched dozens of companies and individuals like myself fail at this, and Agile is not another remake. It is a modest, thoughtful approach to building truly sustainable housing that meets a real need, that deserves to succeed, and likely will.”

There is a teensy bit of straw in my history with the subject of embodied or upfront carbon. I first learned of it from Chris Magwood, who I met when he was teaching straw bale building, and then ran the Endeavour Centre in Peterborough Ontario, and now now manages carbon-free building for RMI (formerly the Rocky Mountain Institute).

His presentations a decade ago about the embodied carbon “elephant in the room” were, for me, the lightbulb moment. He figured this out while working with straw, and I got it from him. And as I note in my new book, when you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes.

If trees are considered “fast carbon” because of how they store CO2, then straw is supersonic carbon, absorbing and storing CO2 in a period of months. It’s no wonder that straw and the people who build with it are at the forefront of the discussion of embodied or upfront carbon.

"The future we want is built with sticks and straw." Absolutely! The low carbon future we want is also likely to be built as walkable urban environments with higher density rather than one or two story single family homes in sub-urban or rural environments. We need a sticks and straw housing construction model that works at the goldilocks density, likely involving four to six story multi-unit residential building types. Light frame wood construction is the low carbon method that is currently best suited to these building types, using prefabricated wood frame structural components. It would be great to see straw based insulation products coming into the market that can be field applied similarly to how we currently use dense packed blown in cellulose or fiberglass. That would be a real game changer in terms of providing the grounds for scaling the use of straw by-product and for further reducing the upfront carbon in the typical assemblies at these buildings. They will need testing to demonstrate fire and sound performance (we practitioners will need listings!) and ideally they will be cost competitive with the current materials.

After 40 years of experience I can say straw is a beautiful way to build. Light straw clay, bales, panels, straw rich adobe, and more. Some of the straw panels have been superb but never reached a large audience. The fire resistant walls with clay, lime or other plasters are very durable with good design detail. I visited some very old straw bale buildings in Nebraska - still porividing superinsulated, quiet, and stable walls. The big bales have been used in Australia and straw bale buildings are around the world. With true cost accounting for climate change we would see many more. The Last Straw Journal has been a good way to keep up. david bainbridge