The three different kinds of obsolescence

An excerpt from my book, Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle

In my recent post, Are the new Apple Watches truly "carbon neutral"? I quoted Raz Godelnik, assistant professor at Parsons School of Design, who noted that “Apple's business model still revolves around selling customers new versions of its products that are released every year. If anything, this makes it a poster child for an outdated business model grounded in planned obsolescence.”

Is it an outdated model? In my 2021 book Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle, I wrote a section asking, “Why we buy” and discussed the concepts of obsolescence. Here is an excerpt that is relevant to the discussion of Apple products.

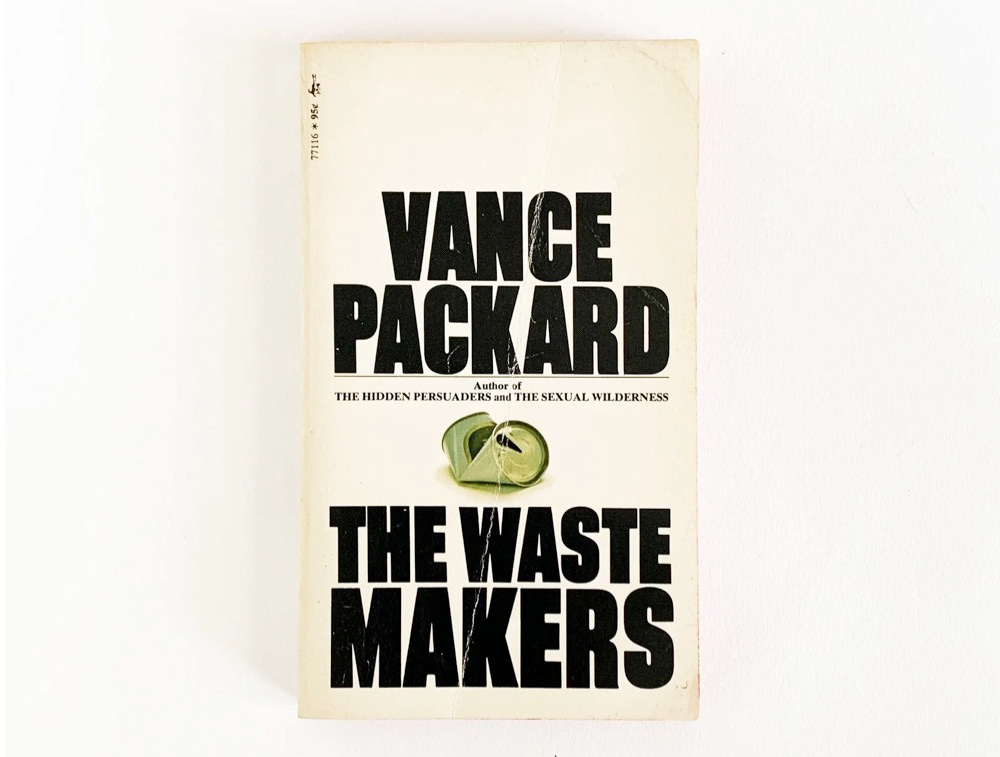

The economist and physicist Robert Ayres wrote: “The economic system is essentially a system for extracting, processing and transforming energy as resources into energy embodied in products and services.” — or as I interpret it, the purpose of the economy is to turn energy into stuff.” But there is no point in making stuff unless someone is going to buy it. The stuff has gotta move. One way to make it move is to create the need or want to replace it. In his classic 1960 book The Waste Makers, Vance Packard quotes banker Paul Mazur:

The giant of mass production can be maintained at the peak of its strength only when its voracious appetite can be fully and continuously satisfied. It is absolutely necessary that the products that roll from the assembly lines of mass production be consumed at an equally rapid rate and not be accumulated in inventories.

Packard also quotes marketing consultant Victor Lebow:

Our enormously productive economy… demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfactions, our ego satisfactions, in consumption.... We need things consumed, burned up, worn out, replaced, and discarded at an ever-increasing rate.

This is why the car-dominated suburban lifestyle was such a success at creating a booming economy in North America. So much more room for stuff, for consumption, creating a need for endless consumption of vehicles and the fuel to power them and the roads to run them on. For the hospitals and the police, and all the other parts of the system. It would be hard to imagine a system that turns more energy into stuff. It is why houses get bigger, and cars turn into SUVs and pickup trucks: more metal, more gas, more stuff. It is why governments are loath to invest in public transit or alternatives to cars: a streetcar lasts 30 years and doesn’t add to the consumption of stuff; there is nothing in it for them. They want a booming economy, and that means growth, cars, fuel, development, making stuff. It’s why they build tunnels in Seattle, bury streetcars in Toronto, and fight over parking in New York City: Rule 1 is never inconveniencing the drivers of cars; they are engines of consumption.

For years, going back to the 1930s, there has been talk about planned obsolescence being built into products. One industrial designer told Vance Packard:

Our whole economy is based on planned obsolescence, and everybody who can read without moving his lips should know it by now. We make good products, we induce people to buy them, and then next year we deliberately introduce something that will make those products old fashioned, out of date, obsolete... It isn’t organized waste. It’s a sound contribution to the American economy.

Packard thought it was more complex than that, and that there were different kinds of obsolescence. There are important distinctions:

Obsolescence of function.

“In this situation, an existing product becomes outmoded when a product is introduced that performs the function better.”

We have been overwhelmed with this in the computer and iPhone age, where the technology really has evolved so rapidly. My recent iPhone 11 Pro has finally supplanted my digital camera, and is demonstrably better than the iPhone 7 it replaced. Before that, I used my 35mm Olympus cameras for 25 years, and then went through six digital cameras in the last 20 years before giving up on them altogether.

But I would make the case that obsolescence of function is a good thing; look at what that phone can do. If you went to Radio Shack in 1990, you would have to buy fifteen different pieces of equipment, from telephones to answering machines to camcorders to calculators; Buffalo writer Steve Cichon calculated that it would cost $5,100 in today’s dollars, and it would fill a room. Now that the iPhone camera is so spectacular, I cannot imagine buying another separate camera. When it comes to obsolescence of function, I say bring it on. Packard thought so too:

“Let us grant that we are all heartily in favor of the functional type of obsolescence that is created by introducing a genuinely improved product.”

Obsolescence of quality.

“Here, when it is planned, a product breaks down or wears out at a given time, usually not too distant .”

Packard quotes a marketer in 1958: “Manufacturers have downgraded quality and upgraded complexity. The poor consumer is going crazy.” Imagine if he were around today. When we renovated our house, I bought a lot of Samsung appliances, all of which have electronic controls. The kitchen stove lasted a year before it wouldn’t hold the temperature; each repair cost hundreds of dollars as the entire electronic guts had to be replaced. I feel incredibly guilty admitting that I gave up and replaced the stove after four years; my mom’s electric range lasted for ten times that long. I bought its replacement on the basis of reviews of dependability and ease of maintenance.

Obsolescence of desirability.

“In this situation, a product that is still sound in terms of quality or performance becomes “worn out” in our minds because a styling or other change makes it seem less desirable.”

This is what drives fashion and interior design; the minimalist look is the thing one year, the cozy hygge look the next. Or people ripping out their granite counters to replace them with more fashionable quartz. Or why, every year, the fronts of pickup trucks get more aggressive and dangerous looking; drivers of older trucks look like wimps. As Paul Mazur noted, “Style can destroy completely the value of possessions even while their utility remains unimpaired.”

This is what is really driving so much waste, what has also been called psychological obsolescence. It’s why buying used or buying classic makes so much more sense, buying design instead of style. I am writing this at a desk designed by George Nelson in 1954 that is still a functional classic. Nelson himself said in Industrial Design Magazine :

Design… is an attempt to make a contribution through change. When no contribution is made or can be made, the only process available for giving the illusion of change is “styling.” In a society so totally committed to change as our own, the illusion must be provided for the customers if the reality is not available.

We have to learn to consciously differentiate design from style.

Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle is available from New Society Publishers in print, digital and audio editions.