The latest design trend: "House hushing"

It is a silly term that gets it backward, and has nothing to do with acoustics.

Forget Hygge; according to Emma Beddington in the Guardian, the latest interior design trend is “house hushing.” When I saw the title, I thought it would be about acoustics, but no:

According to the hushed-living concept, stuff you accumulate, the flotsam of daily life, but also things you have chosen – ornaments, pictures and decorative bits and pieces – create a hum. You probably aren’t even aware of it – a phenomenon often described, in a perhaps unhelpful mixing of metaphors, as “house blindness.” But the cumulative effect can be a jittery blast, like avant-garde free jazz. Fewer possessions, carefully and deliberately selected, can transform cacophony into pure harmony."

Really. It is apparently a bit of minimalism, a bit of Marie Kondo. Another designer notes:

“We’ve felt joy and calm and the home feels way more peaceful. I think it’s down to knowing where everything is and that it has its place. But also, all the crap you don’t need has been cleared out and it gives everything else room to breathe and you have more joy with the items you do have.”

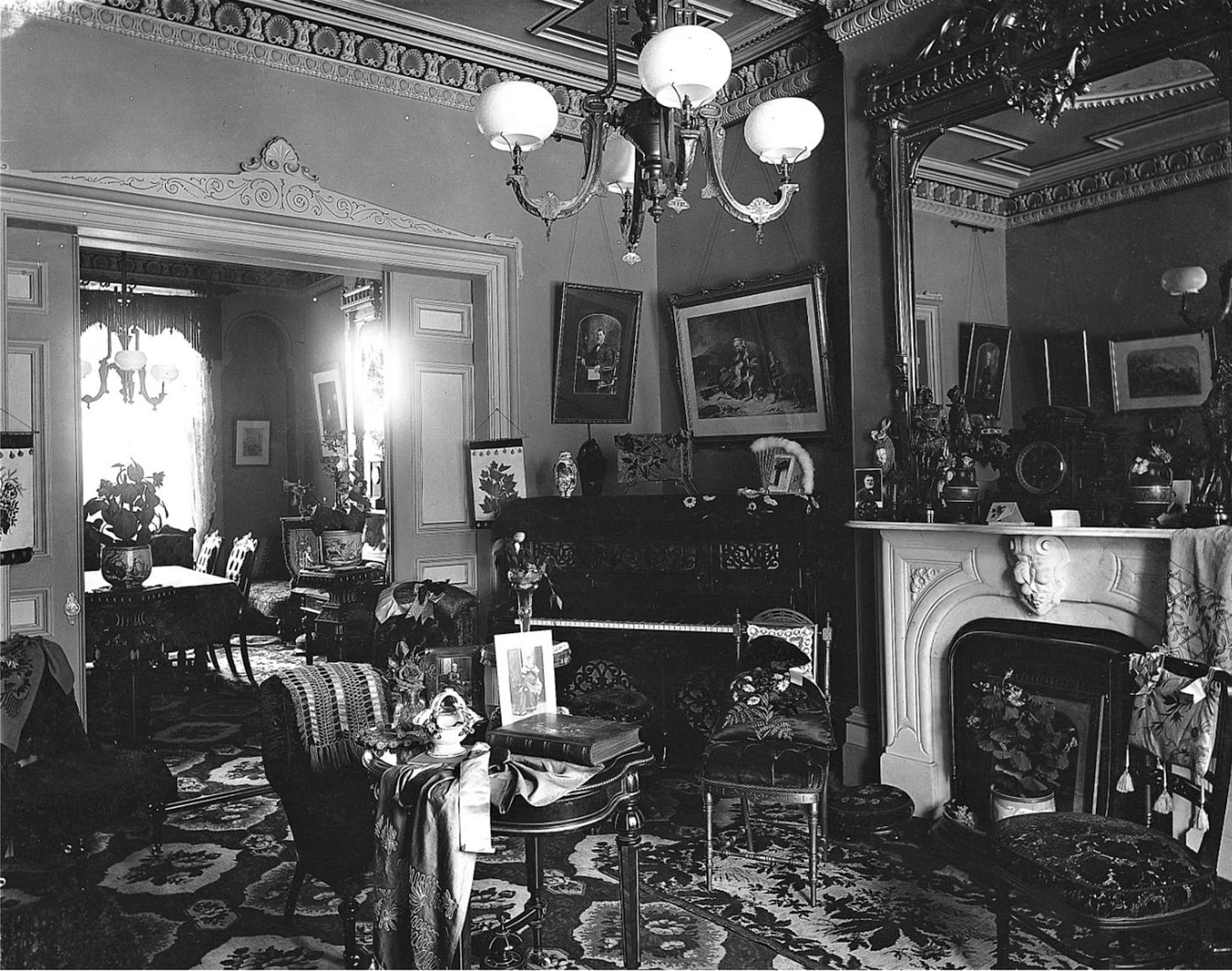

This makes no sense to me; I love minimalism, but it is the opposite of hushing. That’s why I have illustrated this with interior photos by Canadian photographer William Notman, showing the crap and the clutter and tchotchkes in the living rooms of the rich in Victorian Montreal. If the flotsam of daily life creates a hum, then these interiors would be screaming. In fact, it is the opposite; The drapes, and upholstered furniture break up and absorb sound. Books, in particular, are wonderful insulators. Conceptually, these hushy designers have it backward.

True house hushing isn’t just a matter of decoration, it is a function of material choices, design and construction. And indeed, the Guardian article does get around to the physical hushing of noise.

“Our standards are still too low, in my opinion,” says Professor Trevor Cox, head of acoustics research at Salford University. “It’s a really serious issue that is often overlooked.” Cox highlights some common problems: laminate flooring replacing carpet, meaning you hear footfall from above; and common joists between neighbouring houses that allow sound to travel.

The problem starts with design. Kate Wagner, an architectural critic with training in acoustics, agrees with me that much of the problem is our current love of open plans. She writes in CityLab that it’s time to end the tyranny of open-concept interior design.

Not separating cooking, living, and dining is also an acoustical nightmare, especially in today’s style of interior design, which avoids carpet, curtains, and other soft goods that absorb sound. This is especially true of homes that do not have separate formal living and dining spaces but one single continuous space. Nothing is more maddening than trying to read or watch television in the tall-ceilinged living room with someone banging pots and pans or using the food processor 10 feet away in the open kitchen.

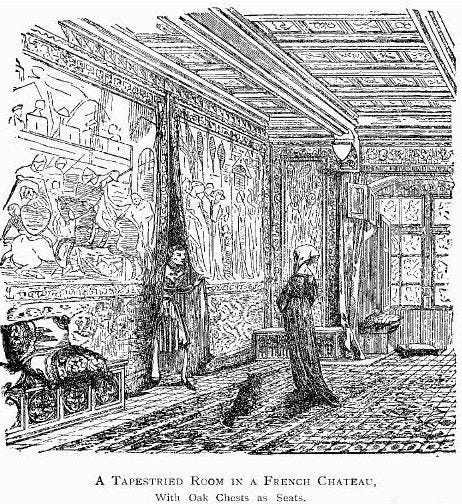

Much can be done with interior design to hush your home. If Victorian tchotchkes are too modern for you, you could go medieval on your walls as the rich in France did; it keeps you warm and absorbs noise, and you could take the tapestries with you.

I rather like this Swedish bedroom with pillows overhead.

Material choice can make a big difference. I would love to live in Cork House, designed by Matthew Barnett Howland with Dido Milne and Oliver Wilton. It won a pile of sustainability awards and was short-listed for the Stirling Prize. It is praised for its low whole-life carbon, but cork is a wonderful insulation and sucks up sound.

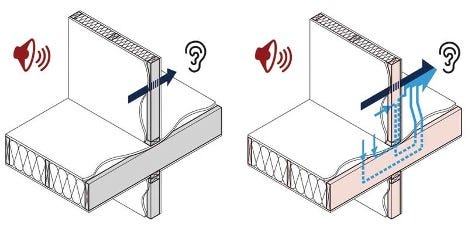

But the most serious problems come from sound transmission between apartments, either through party walls or floors. When I subdivided our house into two apartments, I put in sound-absorbing insulation and floated the floor on cork, but we still got some impact noise. In new construction, it is easier; you can do double layers of drywall with elastomeric glue between, and you can add acoustic isolators. But sound is tricky; it can find its way through ducts and around pipes.

We don’t hear much from upstairs, but we know when their dishwasher is on because of the drainpipe. In our apartment, I chose the dishwasher because of its low dB rating, so low that Bosch put a red light on it so that you know it is on, but there is not much point in buying an expensive, quiet appliance if your plumbing isn’t isolated and insulated.

The problem is that even though most building codes demand a Sound Transmission Coefficient (STC) rating of 50, meaning that it drops the sound level by about 50 decibels, much of the sound transmission is “flanking noise” through ducts and cracks. It’s a big problem with our modern mass timber buildings; there is less mass and a gap around the edges of the panels. That’s why there is often concrete poured on top of the wood. According to Building + Design,

“Almost all mass timber buildings have additional material like concrete or gypcrete,” says Chris Pollock, Associate Principal, Americas Technical Services Leader, Arup. “Resilient underlayments have a significant benefit for mitigating footfall noise and a marginal improvement to airborne sound separation.”

Another interesting point about mass timber buildings is that as they get taller, the loads on the structural elements get heavier, and this affects the noise transmission. A study released earlier this year noted that “results show that increasing load, by an increasing number of stories, has a negative effect on the vertical airborne sound insulation.”

Sound transmission is another good reason to go Passivhaus; A few years ago, I was in Jane Sanders' Passive House renovation of a Brooklyn townhouse, and you could see trucks go by, but you couldn’t hear them at all because of the thicker insulation and high quality windows. A study by NK architects found that going Passivhaus reduced sound transmission by 10 decibels; since it is a logarithmic scale, that means it cut noise transmission in half. It’s another reason I love the Passivhaus concept; you come for the energy savings but stay for the comfort, security, and quiet.

This is true house hushing, which is a lot more than a new name for decluttering.

There are other solutions; I am lucky in that I wear high-tech hearing aids and have a volume control in my head; I can just open my iPhone and turn down the noise. Others might consider a noise-blocking helmet from designer Pierre-Emmanuel Vandeputte, described by the artist:

A helmet made out of cork allowing a person to insulate himself from noise. A mechanism devised with only a counter-weight, a rope and two pulleys helps to move the helmet up or down one’s head. The soundproofing characteristics of cork are clearly evident in the design concept. Encapsulated, we are offered the chance to hear our own silence.

Now, that says hush.