The Isokon shows us how to design for living in small spaces

But it takes a community to really make it work.

I was recently in Paris at the UNEP buildings and climate conference to discuss sufficiency and ask, "How much do we really need?" In recent discussions about upfront carbon emissions, I concluded, "It's apparent that how much we build has far more impact than what we build it out of."

Then, I visited the Isokon building in North London, properly known as the Lawn Road Flats, and saw a fascinating and perhaps extreme prototype for many of the ideas we have been discussing.

Isokon was developed by Jack Prichard, the marketing manager for a successful plywood company, and designed by architect (and Canadian expat) Wells Coates.* They were influenced by the 1933 Congrès International d'Architecture Moderne (CIAM) conference and the idea of the Wohnung für das Existenzminimum or "minimum unit." And wow, they don't get any more minimum than this.

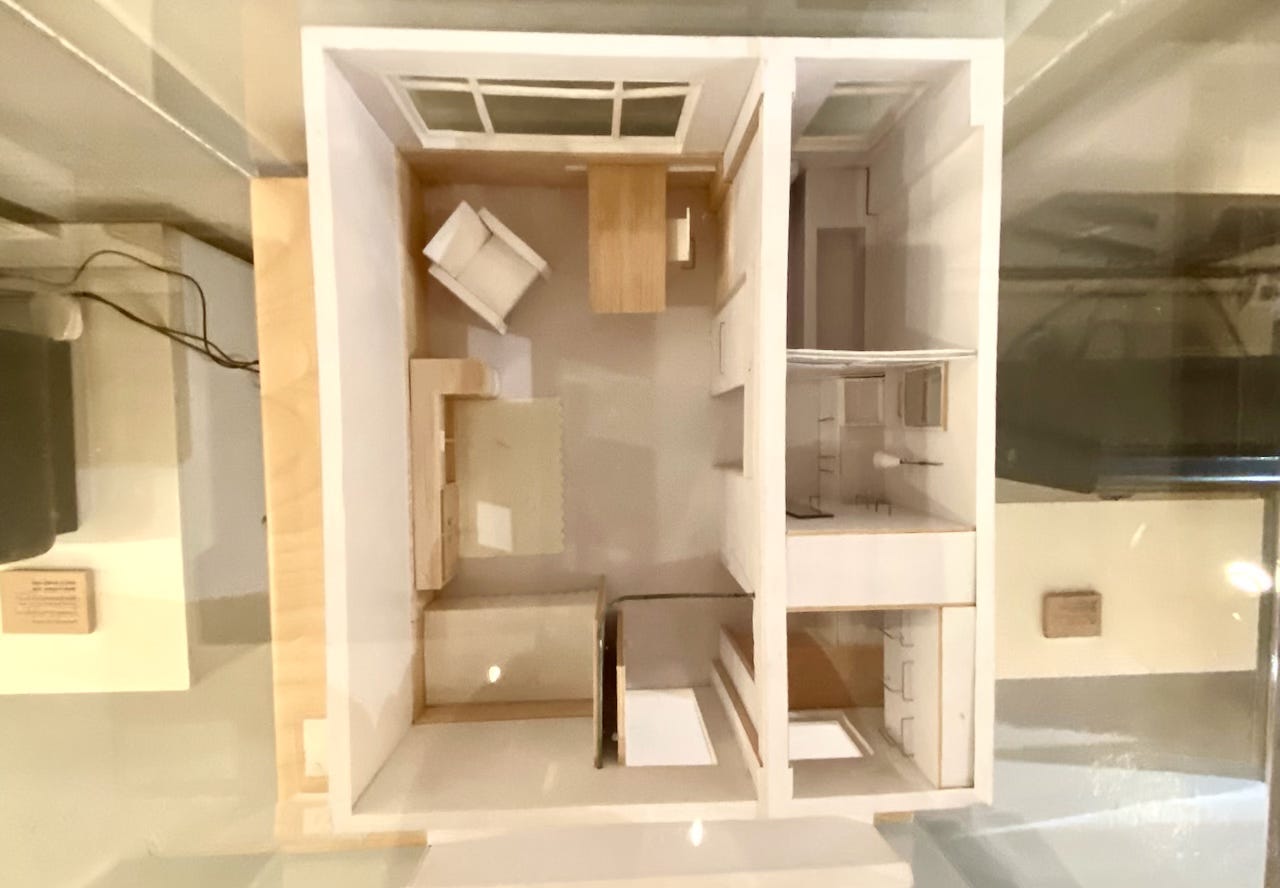

The studio unit that makes up most of the project is 25 square meters (270 square feet). As seen in this model, you enter from an exterior walkway into a tiny vestibule with a kitchen, dressing area, and bathroom.

The owner of this unit (who requested to remain nameless) occasionally opens it for visitors and has filled it with period treasures; even his fountain pen is from the 1930s.

But there is still room for a plywood desk and dining table,

Chairs and tables designed by Marcel Breuer,

A "donkey"- because it looks like a donkey carrying books in panniers, designed by Egon Riss,

And on the desk, the marvellous Isokon Gull carries books and a bottle of wine, also by Egon Riss.

At the other end of the room, there is a day bed and end table by Eileen Gray, which were not in the original design. The tenants didn’t get Eileen Gray but got workable furniture designed by Wells Coates, everything they needed if they were "young professionals with few possessions and a mobile lifestyle."

The original kitchens were small but workable;

This modernized kitchen is totally workable and much improved over the original.

The bathroom and dressing area are positively generous.

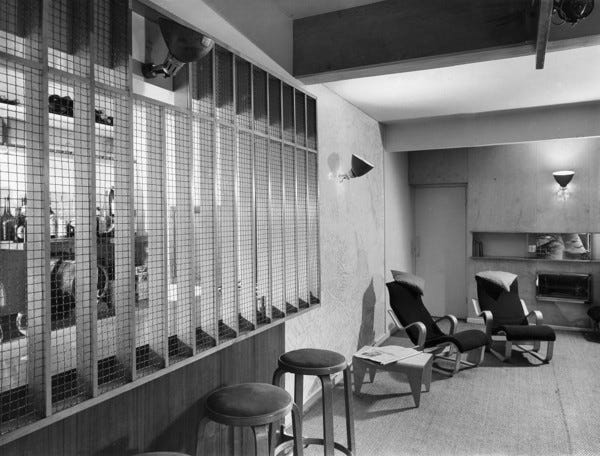

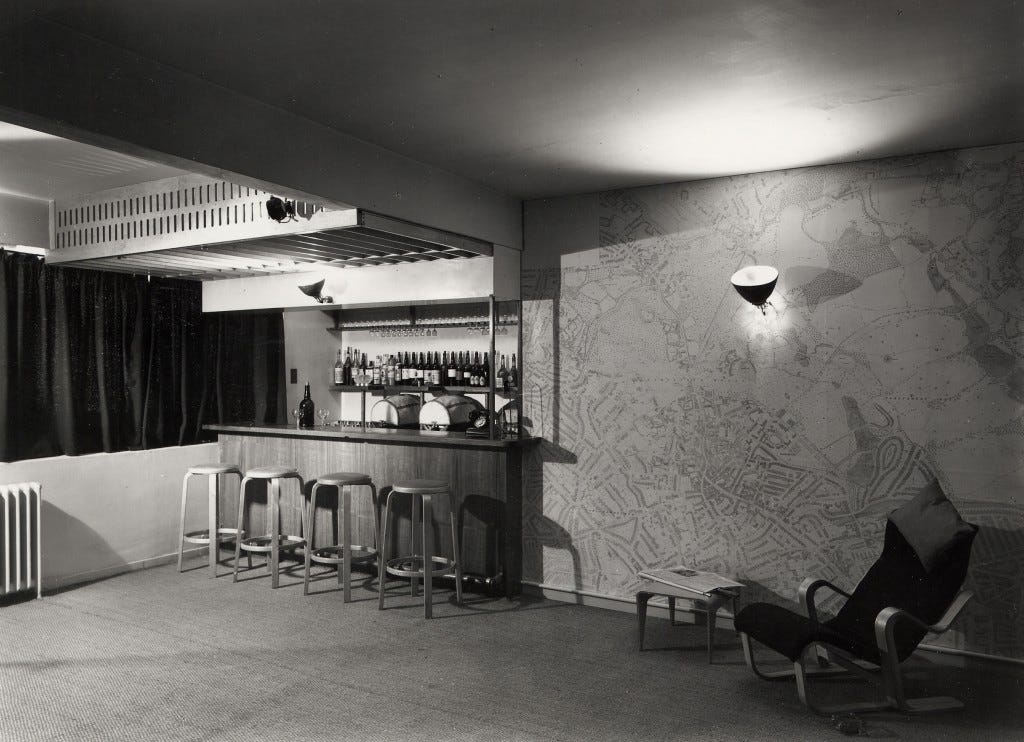

You didn't have to stay in your little room; there was the Isobar, designed by Breuer, with food by Philip Harben, who, after the Second World War, became the first Celebrity Chef on BBC TV. There were also services ranging from shoe cleaning to bedmaking. Dumbwaiters at the end of each corridor were used to deliver meals.

Isokon has been described as "an experiment in collective housing designed for left-wing intellectuals." Indeed, it was full of them, including several Bauhaus emigres, architects and designers Walter Gropius, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and Marcel Breuer, and later, James Stirling. According to the London Historians blog,

The flats – and particularly the bar – became famous as a centre for intellectual life in North London. Notable residents included Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the authors Nicholas Monsarrat, Agatha Christie and her husband Max Mallowan as well as Gropius and Breuer. Agatha Christie lived at 22 Isokon, throughout the Second World War, from 1940 until 1946, suffering all the fears and privations of the bombing. Not only did she write several of her well known crime novels but she was also very involved in writing for the stage, which she loved. When her daily life became too stressful she would take refuge in her flat and in her own words, "lie back in that funny chair here which looks so peculiar and is really very comfortable".

This brings us back to the question: can one live in 270 square feet? Another visitor touring with us today said "I would run out screaming!"

It certainly helps if you have a big window overlooking a green forest. It helps that architect Wells Coates loved boats and designed the built-in furniture and fittings as if the apartment were a boat, where people live in small spaces but have a place for everything.

It also helps if you are part of a community of like-minded people and can spend time together in the Isobar and hang out with Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth.

I think the minimum unit is exactly that- the minimum. But I also believe it is absolutely livable. The tiny separate kitchen with the window overlooking the walkway is more useable than most apartment kitchens today; the owner says, "I can stand in one place and reach everything." The bathroom and dressing area are generous.

The Isokon was almost lost; Jack Pritchard sold it in 1969, and the Isobar was split up into apartments. It was sold again to the local council, but it was poorly maintained and threatened with demolition. A major restoration was completed in 2004, and most of the units are now used as housing for nurses and teachers. A few units like this one were sold on the open market, which is how I was lucky enough to visit today.

There are many lessons one can learn from the Isokon. Single-loaded gallery corridors allow light and air from both sides. The hill I will die on is that the tiny separate kitchen is better than an open one where you have to look at blinking appliances and dirty dishes all night.

But the most important lesson is that if you are going to live in small spaces, you must be part of a bigger community with shared resources. See you later in the Isobar!

*I spoke disparagingly to our guide about Wells Coates being described as "Canadian”, given that he was born in Tokyo to British missionaries, and didn't live very long in Canada before working in the UK. In fact, this graduate of the University of British Columbia came back to design a new town in Quebec (not built by him), the redevelopment of the Toronto Islands, (not built) and according to Wikipedia, "His last assignment was to design a monorail rapid transit system for Vancouver, dubbed the Monospan Twin-Ride System (MTRS). Once again, he was ahead of his time. The project was abandoned, but would be rejuvenated years later in another form known as SkyTrain."

Paul Rossiter of the Isobar Press writes:

“Although a Canadian citizen, Coates was born in Japan in 1895 and spent his first fifteen years in Tokyo; his style was strongly influenced by this early experience, so much so that he told his architecture students in Canada in the 1950s that the only thing needed to be a modernist architect was an understanding of Japanese spatial aesthetics.”

I am developing a deep admiration for Wells Coates, clearly an underrated visionary, and will be looking into his career.

Penguin Donkey is fabulous. Various recent imitations showcased at https://www.onthebookshelf.co.uk/search?q=donkey - the isokon also had a restaurant (for menu sample see https://twitter.com/FamousMenus/status/1451463173123497985)

Thank you for this piece - I got so much joy in reading it. You have reminded me why architecture and design is so exciting.