The end of work

Elon Musk says artificial intelligence will replace all our jobs. He is not the first to make this kind of prediction.

At a recent conference in the UK discussing the safety of artificial intelligence, Elon Musk told British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak:

“We are seeing the most disruptive force in history here. There will come a point where no job is needed. You can have a job if you want a job … but the AI will be able to do everything.”

While there are many who don’t trust a single word Elon Musk utters (Kelly wondered why I would bother writing about what he has to say), this is not a particularly original thought and is one that has been raised with every technological advance since Socrates complained about the invention of writing.

In 2016, the Guardian predicted that “Machines could take 50% of our jobs in the next 30 years, according to scientists,” and produced this video, the story of Alice and the last job on earth.

The future of work is a subject I have been thinking about for some years (since 1985, actually), having predicted the end of the office many times and been consistently wrong. In my book, Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle from New Society Publishers, I wrote a chapter about the carbon footprint of work and leisure and the impact of doing less of the former and having more of the latter. Here is an excerpt discussing the future of work, and how we should fill our increased leisure time.

On Work and Leisure

In 1899, Veblen titled his book “The Theory of the Leisure Class” because there was, in fact, a class of people who had time on their hands, as distinct from those who had to work. There was not only conspicuous consumption but also conspicuous leisure, which he defines as the non-productive consumption of time. Members of the working classes didn’t have much time for leisure, but the rich wanted to demonstrate how much leisure they actually had, thanks to all the people working for them.

“Conspicuous abstention from labour therefore becomes the conventional mark of superior pecuniary achievement and the conventional index of reputability.” The leisure class couldn’t just have it; they also had to flaunt it: “The wealth or power must be put in evidence, for esteem is awarded only on evidence.” This may well explain the consumption of Sea-Doos and power boats and ATVs, all those expensive and powerful toys that people use to fill their leisure time.

Since Veblen was writing back in 1899, there have been radical changes. With the reduction in hours of work and increases in pay after the First World War, many more people had time on their hands. Economists thought it would continue this way; in 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted in the essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren that because of a predicted eightfold increase in productivity, we would be working on average three hours a day by 2030. He thought it would make us better people:

"We shall once more value ends above means and prefer the good to the useful. We shall honour those who can teach us how to pluck the hour and the day virtuously and well, the delightful people who are capable of taking direct enjoyment in things, the lilies of the field who toil not, neither do they spin."

Bertrand Russell wrote in his 1932 essay “In Praise of Idleness” how everyone should now be a member of the leisure class:

"Leisure is essential to civilization, and in former times leisure for the few was only rendered possible by the labors of the many. But their labors were valuable, not because work is good, but because leisure is good. And with modern technique it would be possible to distribute leisure justly without injury to civilization."

He thought that everyone should work fewer hours and have more time for leisure. The problem that he foresaw and that we see today is the issue of “positive idleness” such as painting or writing, vs “negative idleness,” which “ends up being the effect of work under the spell of consumerism and its consequent socioeconomic inequality.”

"The pleasures of urban populations have become mainly passive: seeing cinemas, watching football matches, listening to the radio, and so on. This results from the fact that their active energies are fully taken up with work; if they had more leisure, they would again enjoy pleasures in which they took an active part."

In essence, we are all so worn out from our day at work that we basically flop down in front of the television.

And why didn’t we get all that extra time that Keynes and Russell promised us? According to Benjamin Freidman, writing in Work and consumption in an era of unbalanced technological advance, it’s because of inequality. Basically, all the gains from the increases in productivity went into the pockets of the rich. He quotes economist James Meade, writing in 1965, discussing how having less work and more time would have the opposite effect from that projected by Keynes and Russell:

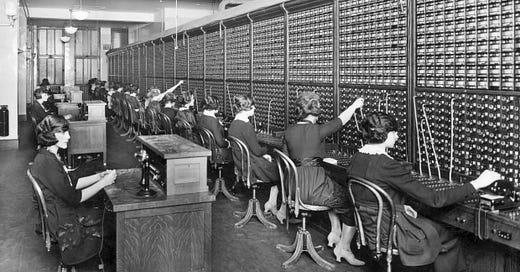

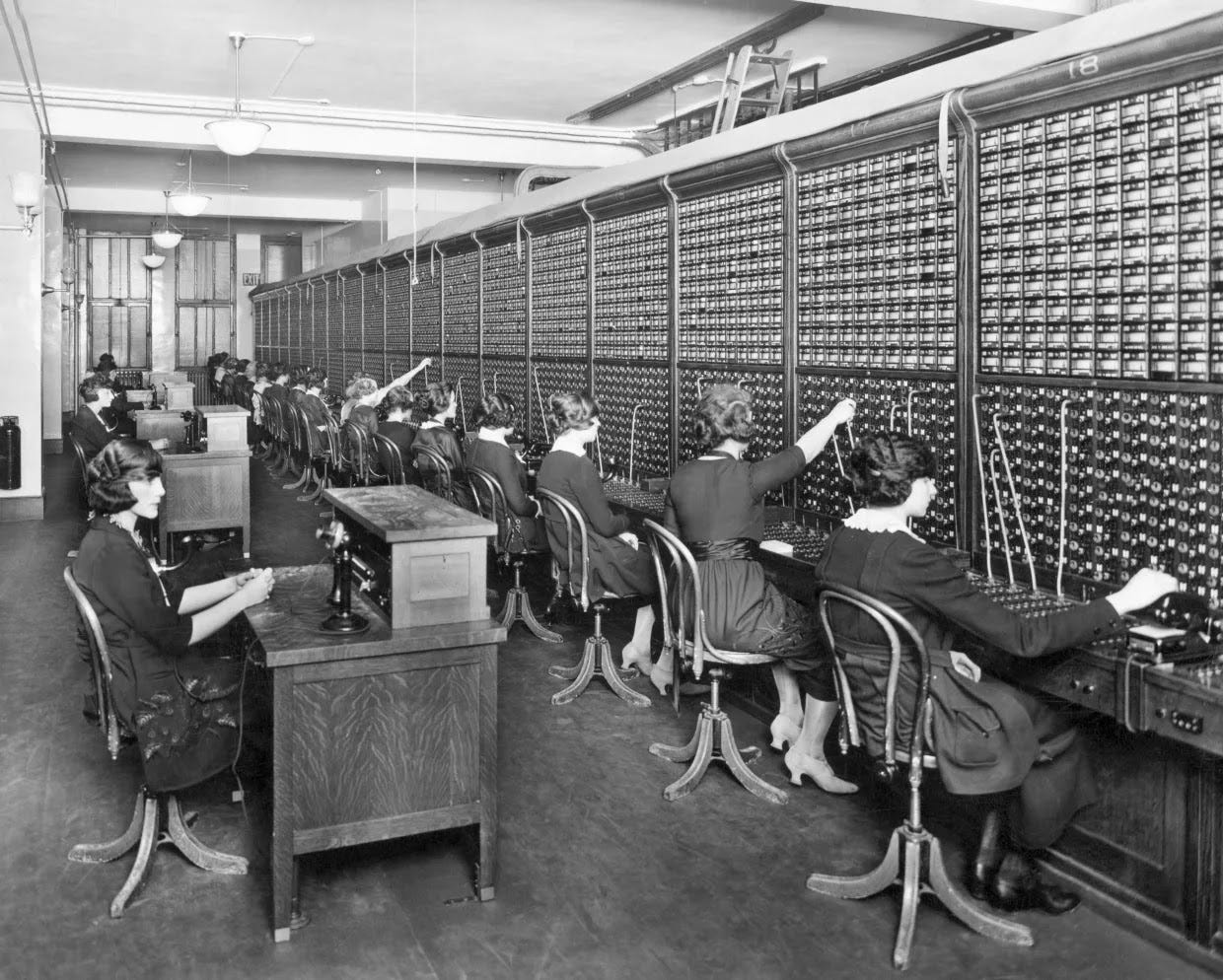

"Meade instead thought “wages would thus be depressed,” as ever less labor was necessary for production. Correspondingly, an ever greater share of total income would go to the owners of the machines. In the absence of government-provided welfare on a massive scale, therefore, most of the workforce would be compelled to take whatever low-paying jobs they could get, presumably in the service of the machine-owners but not working with the machines. In Meade’s vision, “we would be back in a super-world of an immiserized [impoverished] proletariat of butlers, footmen, kitchen maids, and other hangers-on.”

In today’s American context a half- century later, one might substitute gardeners, swimming pool attendants, personal trainers and home nurses.

Which brings us to the concept of degrowth, and unwinding our mad economy based on constant expansion. As Jason Hickel wrote in Less is More, it’s all about distributing income and resources more fairly, liberating people from needless work, and “investing in the public goods that people need to thrive.” He continues, sounding a bit like Bertrand Russell:

"Some critics worry that if you give people more time off they’ll spend it on energy-intensive leisure activities, like taking long-haul flights for holidays. But the evidence shows exactly the opposite. It is those with less leisure time who tend to consume more intensively: they rely on high-speed travel, meal deliveries, impulsive purchases, retail therapy, and so on. A study of French households found that longer working hours are directly associated with higher consumption of environmentally intensive goods, even when correcting for income. By contrast, when people are given time off they tend to gravitate towards lower-impact activities: exercise, volunteering, learning, and socialising with friends and family."

This is why leisure will become an increasingly important part of our carbon picture. In societies with strong social safety nets and less inequality, people have more leisure time and less worry. According to the International Labour Organization, “Americans work 137 more hours per year than Japanese workers, 260 more hours per year than British workers, and 499 more hours per year than French workers.”

The American Time Use Survey prepared by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics found that we have a lot of time for leisure, averaging 5.19 hours per day. Over half of that, 2.81 hours, is spent in front of the television. Add in time in front of the computer surfing or gaming (0.55 hours for men, 0.31 for women), and you have a lot of time looking at screens. Bertrand Russell would be unhappy to know that we only spend 0.32 hours reading or thinking, 0.64 hours socializing and communicating, and 0.31 hours on sports, exercise, and recreation, with a real split between men (0.39 hours) and women (0.23).

When I started this book, I expected that I would be writing long diatribes about people who drive carbon-spewing all-terrain vehicles, snowmobiles and big motorboats instead of bikes, skis, and canoes. But when you study the data, it becomes clear that this is a very small proportion of the population who have the conspicuous leisure and the money to buy toys that they actually don’t use that often.

In fact, most of our leisure time is spent sitting on a couch looking at a TV or some other screen.

I then go through a long section where I calculate the carbon footprint of watching TV, including the production of 700 movies and 500 TV shows per year, and conclude:

If Bertrand Russell thought we had a problem of passivity in 1932, he would be truly shocked today. There is a giant pile of carbon behind every minute of our screen time, which is why it is increasingly important that we turn it off. The real opportunity in reducing one’s footprint of leisure is to substitute as many minutes of passive leisure for active, to get off that couch and get outside. This adds years of healthy living and puts you in touch with your community, making it stronger.

And for all the people who say that our personal actions don’t matter but our collective actions do, perhaps some of that TV time could be put to better use volunteering and taking to the streets.

Elon Musk is a Great man, and we all should be thanking him for his contributions, especially his releasing Twitter from the clutches of the censorious State. But he's a bit of an Idiot-Savant, has made some great calls and good decisions, but also a lot of bad ones, like Hyperloop, Boring and others. His calls on AI are not bad often, but there is no way AI will ever replace ALL work, at least not for centuries.

Tom Hodgkinson is good on this at https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/nov/03/experts-question-elon-musk-vision-of-ai-world-without-work (I think you would like the Idler).