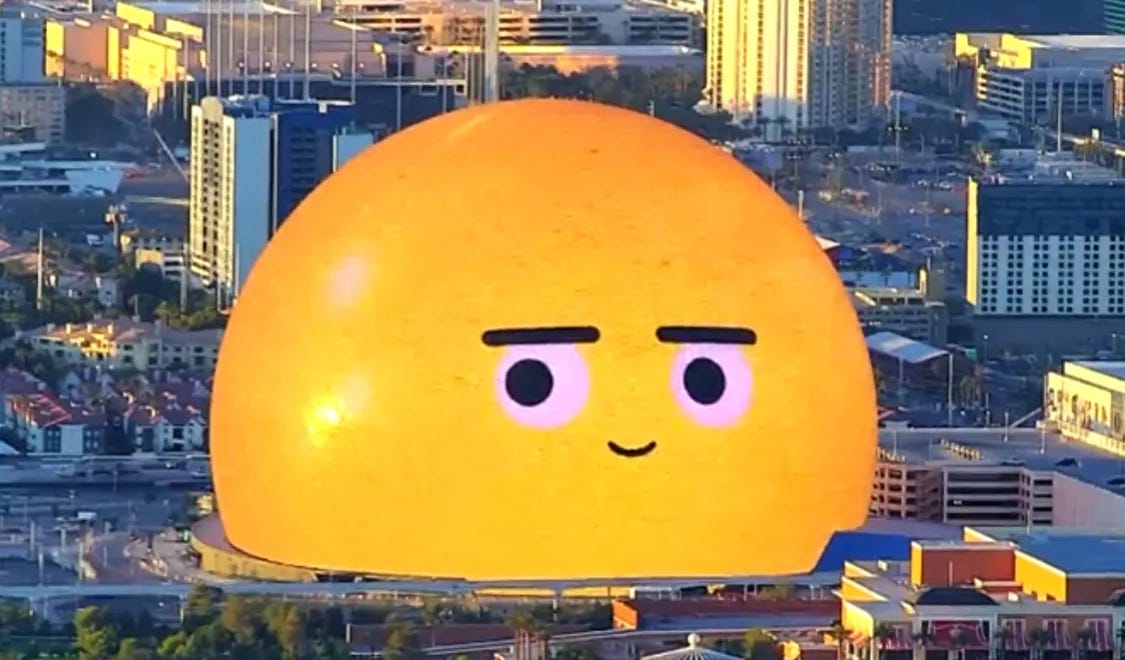

Stanley Jevons goes to Las Vegas

The Sphere eats up the energy and carbon savings from converting 47,889 houses to LED lighting; a bright example of Jevons' Paradox.

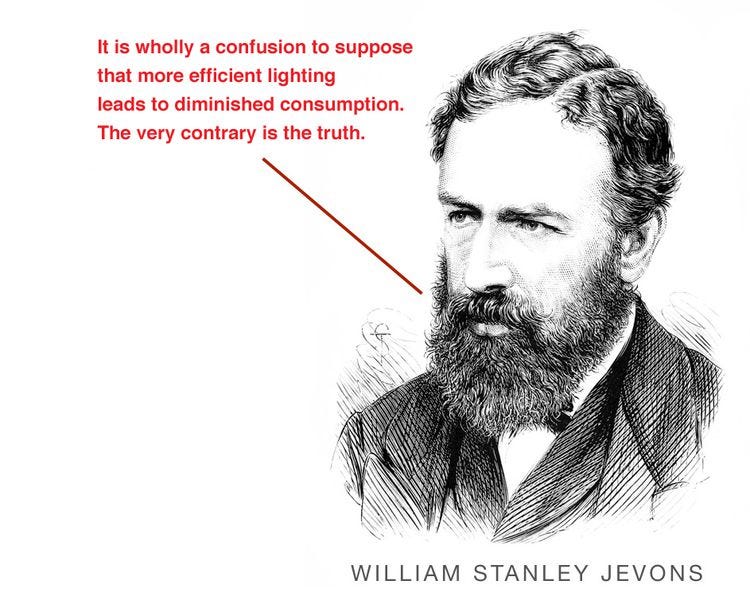

Jevons’ Paradox has been bouncing around in discussions about climate action ever since the so-called “eco-modernists” glommed onto it as a way of justifying doing nothing about energy efficiency since, according to Jevons, we will just use more of it. Jevons wrote in The Coal Question:

There is hardly a single use of fuel in which a little care, ingenuity, or expenditure of capital may not make a considerable saving. But no one must suppose that coal thus saved is spared-it is only saved from one use to be employed in others, and the profits gained soon lead to extended employment in many new forms.

Jevons’ paradox implies that efficiency will lead to bigger cars and houses or other uses (I saved money on gas, let’s fly to Las Vegas!). That’s the rebound effect or backfire. But as this quote suggests, even if we get an ingenious new way of saving energy, we get new forms of exploitation.

I have been arguing about this with Zach Semke of the Passive House Accelerator for almost a decade; He claims that if there is a rebound effect at all, it’s small. I generally agree, but I have often pointed an exception: LEDs. And as uncontrovertible proof, I offer The Sphere in Las Vegas.

Jevons wrote The Coal Question after James Watt developed the condensing steam engine that used 75% less coal than the Newcomen engine it replaced. It was not an incremental increase in efficiency but a technological breakthrough. It was so efficient that engineers started thinking up wild and crazy new uses for it, putting it in factories, on ships and even sticking wheels on it and running it on steel rails.

LEDs are having a similar effect. They have not just replaced light bulbs but have changed the way we use light. I have seen living rooms with a grid of 30 fixtures on the ceiling and dining rooms where you could do surgery on the table. LEDs assembled into screens have transformed our phones, computers and TVs. Architects have been encrusting building exteriors with them, but there has been nothing ever like The Sphere. Aaron Timms, in an article titled Sphere eats the Soul, describes it:

“Everything about the structure is big, designed to blow you away, both figuratively and literally: it’s the world’s biggest spherical structure, contains the world’s biggest LED screen, and boasts the largest concert-grade audio system on the planet (with 1,586 loudspeaker modules and 167,000 speaker drivers, amplifiers, and processing channels), while the exterior shell contains 1.2 million hockey puck-sized LED panels that can be programmed to create colossal image displays. These numbers are so impressively, almost meaninglessly gigantic they induce their own kind of statistical vertigo.”

That’s 53,883 square meters of LEDs. The interior features 14,864 square meters, the equivalent of four football fields. The estimates of electricity consumption are almost meaninglessly gigantic, too; One estimate on Twitter claims it draws 150 terawatt-hours of electricity per year. A more plausible one from S&P Global Market Intelligence says the Sphere consumes about 95,779 MWh annually. Its peak load is 28 megawatts, equivalent to the power required to run 21,000 homes.

Based on the carbon intensity of the Nevada grid, running the Sphere will produce 46,835 tonnes of CO2 emissions per year.

LEDs are efficient, and it is estimated that converting an average house from incandescent to LED will save about 2,000 kWh per year or two mWh. That means that the Sphere is negating the savings in energy and carbon emissions from converting 47,889 houses. What is the point of promoting energy conservation in lighting when one Sphere can wipe out a small city’s worth of savings?

The Sphere is apparently wildly successful; the designer says it is changing entertainment forever. Versions are being pitched all over the world, although it was just rejected in London because of concerns about light pollution. Timms concludes:

“Structures like the Sphere take all the worst features of modern consumer technology—the addictiveness, the anti-circadian light pollution, the kitsch—and expand them to the scale of the city. This is architecture as engagement, the facade as marketing scheme, a culture of distraction for distraction’s sake made violently material.”

The energy consumption is violently material, too. But it also proves that Jevons was right; if you make a better light bulb, it will multiply by the billions, and the energy “is only saved from one use to be employed in others, and the profits gained soon lead to extended employment in many new forms.”

I have been complaining about this since 2012 when I first saw a screen with a car ad mounted over a urinal in Noce, a fancy restaurant in downtown Toronto. I worried that we faced a future with LED screens everywhere. Ever since, I have often been ridiculed for suggesting that if you total up the vastly increased lighting levels and all the new ways we have been figuring out how to use and misuse LEDs, we might be eating up all the savings from the technology.

That’s why I go on about sufficiency and using less stuff. I quote Lewis Akenji of the Hot or Cool Institute: “Efficiency is blind to the upper limits of consumption and emissions, and so we can keep improving our efficiency even as we transgress the planetary boundaries.” I also quote Australian writer Samuel Alexander: "Efficiency without sufficiency is lost.”

At some point, we have to decide what is enough, what we really need, and what is ridiculous excess and waste. There is a direct line of ridiculousness, pointless consumption, and unnecessary carbon emissions between that screen over a urinal in 2012 and The Sphere today.

Five years ago, I was complaining about a building that was covered in “interactive media displays” made of LEDs, writing, “I worry about birds, about people trying to sleep, about distracted drivers. And, of course, the energy being used to run building-sized monitors.” I noted that Zach Semke might be right about limits to the rebound effect but concluded:

LEDs are an entirely different thing; we use them in entirely different ways that nobody ever dreamed of, and we use way more of them. Lighting has become so cheap that it has turned into a bauble, into decoration. When it comes to lighting, to paraphrase Jevons, “It is wholly a confusion to suppose that more efficient lighting leads to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth.”

Just look at the Sphere.

Hi Lloyd - the debate continues!

According to the US Energy Information Agency:

• US energy use for residential lighting has plummeted from 130 Terrawatt-Hours per year in 2015 to 62 TWh per year in 2023. That's an LED-propelled energy efficiency savings of 68 TWh per year. (SOURCE: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-09-07/the-incredible-shrinking-energy-use-of-a-light-bulb)

• As you report, the sphere uses 0.078 Terrawatt-Hours, per year according to S&P Global Market Intelligence.

• That means that the US would need to build at least 872 Spheres to offset the annual efficiency savings in residential lighting that we've realized just recently, and that doesn't even account for the lighting efficiency savings in non-residential sectors.

The Sphere is a huge energy waste, but it does not prove that there's an LED efficiency backfire at work or, honestly, that we should be spending our time and energy on the Jevons Paradox. The Sphere is a weird, wasteful outlier that is dwarfed by the lighting efficiency gains that we're seeing in millions and millions of homes across the US. Should we decry its waste and conspicuous consumption? Absolutely! But is the "Jevons Paradox" undermining LEDs as a powerful tool to reduce overall energy consumption? No, at least certainly not based on the numbers above.

The reason I find the Jevons Paradox narrative so frustrating is that, in my view:

(a) It falsely leads people to think that efficiency backfires, like your paraphrased quote of Jevons: "It is wholly a confusion to suppose that more efficient lighting leads to diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth." This statement seems wholly incorrect. Yes, the Sphere is ridiculous, and you could argue that its overconsumption is an efficiency "rebound" where efficiency gains of LED technology are wasted. But the scale really matters here. Even the Sphere's outrageous consumption PALES in comparison to the "diminished consumption" that LED lighting has brought to buildings across the US. Will there be more Spheres or Sphere equivalents? Probably a few. Not 872.

(b) Once you've waded through the "backfire" myth/misunderstanding we're left with this banal insight: "efficiency isn't perfect". Well, of course not! This Energy Journal survey of the literature found a 10-30% rebound in the residential and transportation sectors and a 0-20% rebound in the industrial sector: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421500000215

So, energy efficiency ain't perfect at reducing energy consumption, but it's damned good at it.

Who ever expected any given climate solution to be perfect in the first place? At this point, solutions that get us headed in the right direction with velocity are a good start. As Hannah Ritchie states in "Why Climate Tribalism Only Helps the Deniers", let's be "directionalists" rather than "destinationalists":

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/jul/10/the-big-idea-why-climate-tribalism-only-helps-the-deniers

Another great example are WiFi routers. They use a tiny amount of electricity but are everywhere. In the NYC subway there are multiple routers at every station. On the street NYC placed LCD signage called linkNYC. It will give you alerts about buses and trains but also has a wifi router. Those are at every other block by major streets. Every office building, private residence and store has multiple routers. And the crazy thing they are never turned off. We have blanketed the environment with routers and in the end the tiny amount of energy becomes huge. And the WiFi router is redundant since the environment is already blanketed by cellular towers. Both are transmitting the same internet.