Social housing project embraces radical and elegant simplicity

Montgomery Sisam Architects design a very Euro building for Peel, just north of Toronto.

In 2018 I attended the International Passive House Conference in Munich, and heard British engineer Nick Grant describe “Radical Simplicity,” where simple forms and appropriately sized windows make buildings more efficient and less costly. I then wandered around Munich and saw that most of the new buildings were simple forms with smaller but nicely proportioned windows, like nothing I had seen back home in Toronto.

I became a devotee of radical simplicity and would often quote industrial designer Dieter Rams’ tenth principle:

“Good design is as little design as possible. Less, but better—because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials. Back to purity, back to simplicity.”

I noted in an earlier post that we need “Simple, modern forms, not too many windows but a careful eye to their placement and proportion, and you can have really nice housing to really high standards of energy efficiency, at reasonable costs.”

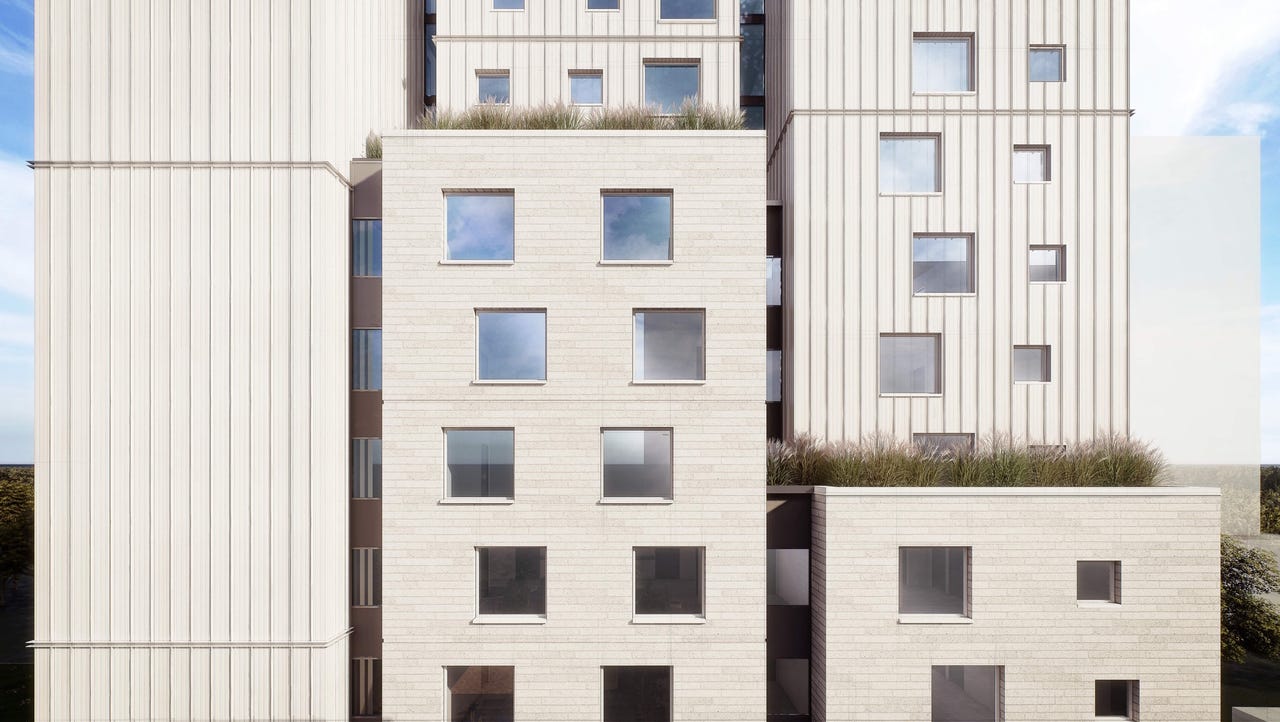

This is why I was so shocked and surprised when I saw the renderings for Montgomery Sisam’s Chelsea Gardens Net Zero Affordable Housing designed for the Region of Peel, just outside of Toronto. It didn’t have seven different materials in the style we call “sample-board modern.” It didn’t appear to have bumps and jogs, but was proudly straightforward, simple and what Passive House architect Brownyn Barry hashtagged #BBB- “Boxy But Beautiful.”

I have rarely commented on individual buildings on this site but I had to call up Montgomery Sisam partner Daniel Ling to discuss it. Right off the bat, he described it as “elegant simplicity.”

Ling told me that most new buildings are now about 60% solid to 40% glass, but a good wall is 10 times as energy efficient as a standard window, and the only way to do an efficient and affordable building is to reduce the amount of glass.

Chelsea Gardens comes in at 18% glazing; the balance of the wall above the ground floor is clad. in “inexpensive aluminum, what you use on roofs and warehouses.” The key is to design the windows from the inside according to their function. I have quoted engineer Nick Grant before, noting that windows can cause “overheating in summer, heat loss in winter, reduced privacy, less space for storage and furniture, and more glass to clean.” He suggests that “size and position are dictated by views and daylight.” Daniel Ling says much the same thing; the bedroom window is higher for privacy, and at about 3 foot square, big enough to make a connection to outdoors. The big glass is put into the living areas.

The building isn’t all flat and it isn’t all aluminum; there is a fair bit of articulation on the west side, and there are more durable materials like brick and block closer to grade.

I was actually suprised that their money shot, the rendering that every post and story leads with, is that totally flat south elevation rather than the busier west side. Perhaps it is because simplicity is so rare here that it stands out. It stands out for its energy and carbon efficiency too;

“Chelsea Gardens is intended to be a new benchmark building, targeting a Zero Carbon Design seeking certification under the CAGBC’s Zero Carbon Building Standard Version 3. Its design also adheres to the requirements of the Region of Peel’s Net Zero Emission standard, including an annual EUI [Energy Use Intensity] of less than 110 kWh/m2 and TEDI [Thermal Energy Demand Intensity] of less than 32 kWh/m2. This performance is achieved largely by way of a geothermal loop with distributed geothermal heat pump system, energy recovery on most ventilation systems, a high resistance envelope, 20% window to wall ratio and ultra-low flow fixtures.”

The plans also stand out, much more European than we usually see. The units are not the usual tiny deep studios; there is a mix of one bedrooms (green) two bedrooms (blue) and gasp, three bedrooms! (purple) the H-shape corridor plan is clever- if my recollection of the building code is correct, dead end corridors where you can only go one way to an exit are limited in length to 6 meters; then you need to have a choice of two exits, here put together into a scissor stair. This clever plan gets natural light into the corridors and permits units that are not bowling alleys. Note how even the three bedroom unit only has one bathroom- this is affordable housing after all.

This is not affordable housing. It’s Bjarke Ingels’ King Toronto Project that might be described as “radical complexity,” where units cost a fortune to build, to buy, and will cost even more to maintain. Elton John bought a unit. Elton John can afford it. I show it to make a point; all the critics love it but I do not see any beauty or elegance. I just see roof leaks and surface area and too much glass and fifty years of paying roofers and legal bills. We need less Bjarke.

We need more Daniel Ling and his team at Montgomery Sisam. We need lots of affordable family-sized units that won’t cost the earth to heat and cool and maintain. We need lots more radical and elegant simplicity.

First, a point of clarification: as far as I know, the first book entitled Radical Simplicity (Small Footprints on a Finite Earth) was written by Jim Merkel and published in 2003. I like your term radical sufficiency even better.

Here's one comparison of simple vs. complex: I was the environmental building consultant on the MIT Sloan School building by Moore Rubell Yudell close to 20 years ago. We set stringent performance metrics, including peak heating and cooling demand on the central utilities. On a day that exceeded design conditions, the cooling demand was 1,100 sf/ton (a bit under 35W/sm). About 1/3 of a typical new building. I can't link images, but that building is mostly punched openings and simple volumes, and even the glazed end towers are mostly highly insulated spandrel. Another building on campus built not long before by Gehry Partners is more in the "look at me" spirit of the Ingels' projects you've written about (though without loveliness in my eye) and with a similar building program, the Gehry project used 2.7 times as much energy per sf as the Sloan building. And it leaks.

I'm an engineer. To me, one signifier of a talented architect is the ability to make a box look good. In NYC Chris Benedict is one such architect. At the smaller scale of wood-frame affordable multi-family housing I'm working with Union Studio (Providence RI) on several projects here on Martha's Vineyard, where construction costs are nutz. At the outset of our first project I drew the simplest high performance wall section I know how to do and we agreed on that as the basis of design. Roof trusses with blown-in cellulose mean no mechanicals in the attics - simplicity often imposes more, not fewer, design challenges. The six unit buildings are two rectangles joined by an entry/stair element. Twelve corners total. Maybe the housing trust will be able to afford to build these.

An excellent apartment building. The only things I would change is that if we're building a 3 bed 1 bath today, the shower and toilet would be in separate rooms and each bedroom would have its own sink and medicine cabinet. One person taking a shower should not block someone else from brushing their teeth or using the toilet.