Should we value upfront carbon savings higher than operational carbon savings?

It's easier to measure a bird in the and than two in the bush.

The engineering firm Arup recently published The time-value of carbon, described as “an introductory exploration to support better decision making, and in which they ask the question, “Should we value upfront embodied carbon savings higher than operational carbon savings?”

It is a question that I have been thinking about for years, and have been wrestling with as I prepare to do a keynote lecture to the Passivhaus community in New Zealand later this week. I hoped this report would help me clarify the issue. Alas, it did not; the more I read, the more frustrated I got. It is a technical report that “has distilled three discernible arguments for valuing future carbon emissions lower than those of the present (i.e. arguments for delaying emissions). These arguments have been characterised as follows:”

The authors are talking about delaying emissions; I think we should be talking about eliminating them. They continue:

A fourth argument of note considers the value of delaying emissions insofar as the delay avoids triggering climate tipping points (e.g. disintegration of polar ice sheets, shifting monsoon rains or. dieback of the Amazon rainforest). Albeit these thresholds are hard to predict. This argument has not been considered further within this report and may be picked up in the future.”

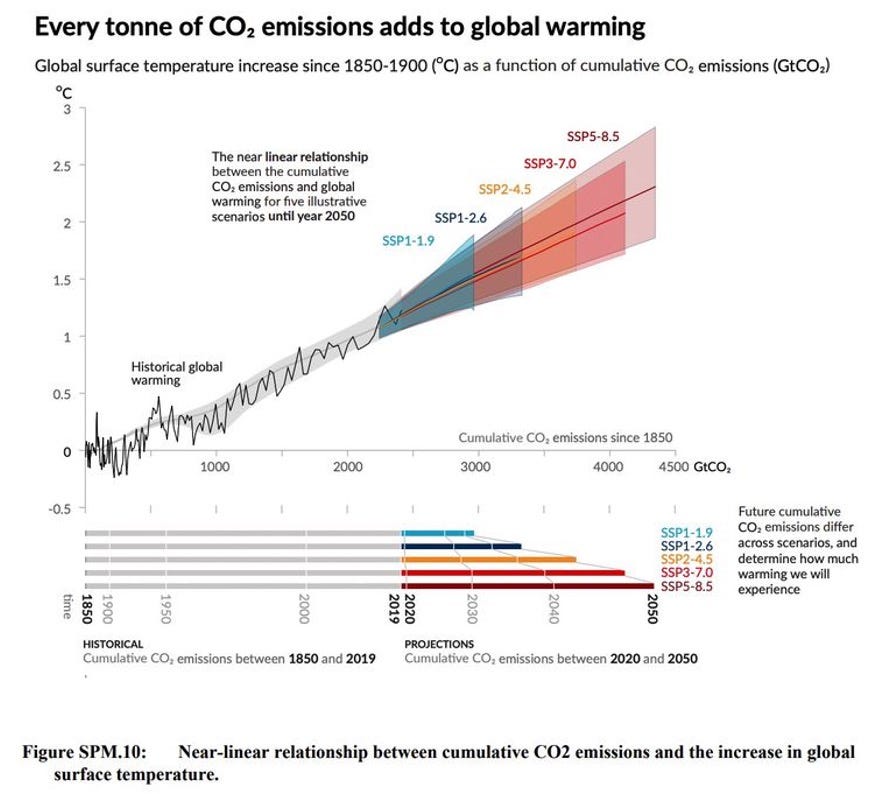

Now I would have thought that fourth argument was pretty persuasive and should be picked up now; I have spent the last few years trying to make the point that it is all a matter of how much carbon we put into the atmosphere.

Every tonne, every kilogram, every ounce we add now goes against the budget ceiling and adds to climate change. Now matters more than later. When it comes to carbon I am a strict Keynesian; the economist John Maynard Keynes wrote in 1923, ‘The long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead.’

The ARUP report is all about figuring out what the real time-value of carbon is so they can put it into life cycle assessments, so that they can meet legal requirements for reporting whole life carbon emissions. I am not an expert on LCAs, but this whole report seems to complicate things so much. I am reminded of Bull Durham, where the coach says "This is a very simple game. You throw the ball, you catch the ball, you hit the ball.”

I may be naive, but I think carbon emissions are a simple game. You do everything you can to reduce them, both now and later, both upfront and operating. It gets so complicated when you talk “whole life” and people start trying to figure out how long materials last and what happens down the road.

With wood, the report notes, “Without assurances on the end-of-life scenario, it is typically assumed the sequestered carbon will be emitted to the atmosphere at the end of its life.” But why make that assumption? When is the end of its life? The report tries to quantify the difference over the life of the building whether one uses current LCA methods and one using Time-Value of Carbon where the future emissions are discounted and yes, TVoC looks better. But is it meaningful? Everything beyond A1-A5 is speculative and they both start from the same base, and there are many who will argue that the base number is guesswork as well.

As shown in the image at the start of this post and here, I have seen wood that has been holding up brick buildings in Bologna since the 13th century. We have no idea how long it will last or what will happen to it. Much depends on how it is designed and maintained. I don’t know how long CLT’s glues will last, but I suspect that DLT panels could have value for hundreds of years. Why can’t we assume that wood can last as long as concrete?

Then the report gets into the thorny issue of “carbon payback periods:”

Designers are often required to explore design decisions which impact both the embodied and operational emissions of a building. For example, triple-glazing versus double-glazing. ‘Carbon payback periods’ are increasingly being used to help designers balance these design decisions, by evaluating the time over which the additional upfront embodied emissions are compensated for by reductions in operational emissions.

But again, this gets contentious and difficult. In an electric world It depends on the electricity supply, where the carbon content varies not just with location and supplier, but the constant trading of electricity between networks. Some networks, like in Ontario Canada, are getting dirtier as more gas peaker plants come online, and run longer than they were supposed to. Other grids are getting cleaner with the rapid deployment of solar and batteries.

If you assume that if triple glazed windows have higher upfront carbon emissions than double, then maybe you should just make them a bit smaller. The window manufacturers are also on this case, and redesigning to have lower upfront emissions.

There are also so many other factors; does going with double-glazing reduce comfort or resilience and increase noise? Nothing about this is a simple tradeoff. Ultimately I always fall back on sufficiency, and just use less stuff.

The only person who gets this right is Yogi Berra, who said, "It is difficult to make predictions, especially about the future."

Post will be erratic for the next two weeks as I am travelling to New Zealand to speak at a Passivhaus conference. Yes I know this has a huge carbon footprint (two years worth at my Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle) and I cannot justify it, but it seems like a once in a lifetime opportunity. Perhaps there is a post in trying to justify it.

Hi Lloyd,

I'm really pleased to see you've engaged with the report and appreciate your review—this is exactly the kind of discussion we aim to mainstream, particularly as these techniques are already appearing in practice.

I agree with your emphasis on reducing emissions, and I also recognize the importance of simplicity in achieving this. This is why we are careful in recommending how these methods are applied (as outlined on page 34). Contrary to your interpretation, we do not advocate for the broad application of these approaches in whole-life carbon assessments, precisely because we recognise the need for assessments to be simple and globally harmonised.

That said, our report aims to support industry practitioners who are forced to grapple with the trade-offs between emissions occurring at different times. Here we do advocate for using these techniques in support of specific project decision-making, precisely because they help to underscore the importance of reducing emissions sooner rather than later.

On the '4th argument' regarding tipping points, I appreciate your attention to this critical issue. While we agree tipping points should be central to the conversation, quantifying this argument is notoriously difficult—though it's a great opportunity for further exploration. Some initial thoughts:

• The scientific community acknowledges the complexity of predicting tipping points like Amazon dieback or polar ice sheet disintegration.

• These tipping points generally occur at specific 'warming levels.'

• Warming is proportional to the ppm of CO₂ in the atmosphere.

• This suggests there may be value in 'delaying emissions' if the delay can reduce the peak concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere.

• Forecasts on when the world will reach 'peak emissions' vary widely, complicating the practical application of this argument.

Despite these challenges, I believe the qualitative value of this argument is significant, and practitioners should be aware of it. In facing such uncertainty, a 'precautionary approach'—focusing on reducing emissions sooner—seems prudent.

Thanks again for engaging with the report, would be delighted to pick-up the discussion further on a call (feel free to reach out).

Kind regards,

Will Wild

The whole time element really is the rub, ya? As a carpenter/designer I think about this all the time. A high carbon material that is in place for a few hundred years is potentially more sustainable than a low-carbon material that gets thrown in the landfill 10 years later because someone wants their kitchen to look different. And yet, knowing this is irrelevant because I never know how long something will avoid the landfill. Sadly, in today's wasteful culture, my assumption is always that that time will be shorter rather than longer...